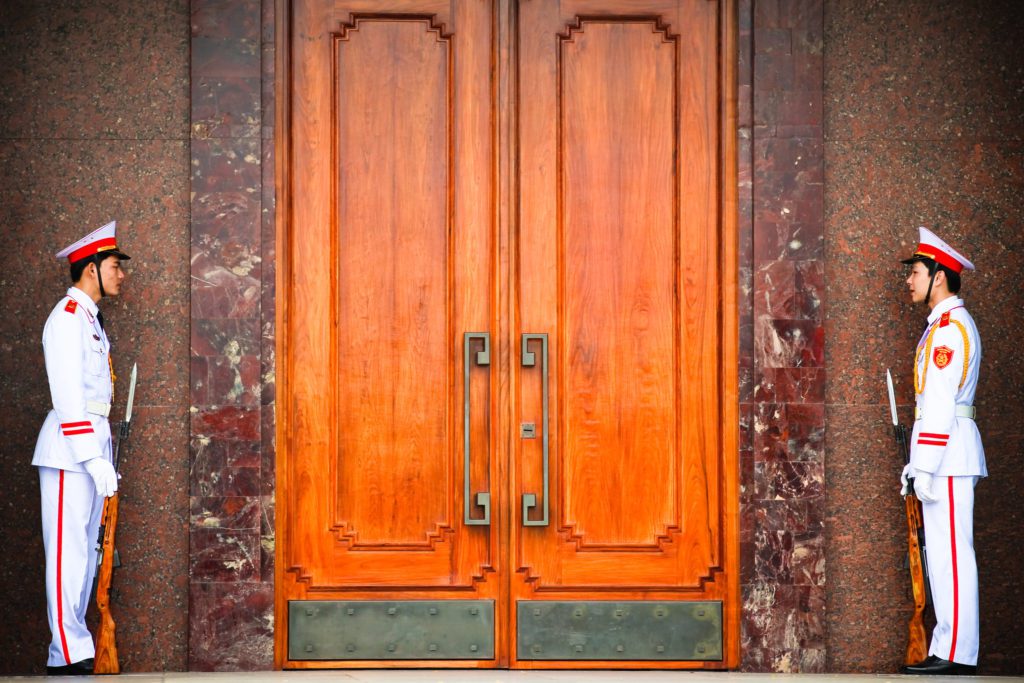

Inside a crystal urn in Venezuela’s Museum of the Revolution, visitors can view the body of Hugo Chavez, the socialist strongman who died in 2013 and bequeathed his battered country to Nicolas Maduro. It was Maduro who decided that the people needed Chavez in perpetuity, citing the example of the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum in Hanoi, where the embalmed Communist leader who humbled the American empire is kept fresh and on public display. The father-and-son dictators of North Korea Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong Il were also embalmed and put into exhibits. While visiting Tiananmen Square several years ago and foolishly bickering with our guide about Mao Zedong’s legacy, I discovered that the man himself still lay in state a stone’s throw away.

Communist dictatorships, launched as they are by charismatic revolutionaries, inevitably become necrocracies. Mao Zedong was the Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party from 1945 until his death in 1976, and his face is omnipresent in the militarized capital of Beijing. An enormous portrait of Mao hangs at the entrance to the Forbidden City; his face adorns the currency; he is the bulky shadow behind the shady machinations of Xi Jinping. At least 45 million people died during Mao’s Great Leap Forward, and historians estimate that up to 70 million perished before he followed them into the grave—although Mao was not cremated as he requested. His presence was too valuable to the Communist project, and thus he was embalmed and placed in a glass coffin in the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall within earshot of where the Tiananmen protestors would be gunned down in 1989. He is still attended by a military honor guard.

I had to wait in line to see him. People ahead of me bobbed their heads in genuflection at his coffin and left him bouquets of flowers. I will confess to gawking when I got inside. Mao lies like a sinister Snow White under a red Communist banner. He had been gone for 39 years when I came up to his coffin, but he genuinely looked like he was sleeping. I wondered if any of those coming to see him—many of them obviously old enough to remember his reign of terror, which touched nearly every family in China—were just there to confirm that he was, in fact, dead. If so, probably a few were not altogether reassured; I would have been shocked but not surprised if Mao had suddenly sat up and begun barking orders once again. The cool Memorial Hall was heavy with his presence.

The only similar experience I can recall was visiting Lenin’s Mausoleum in Moscow several years later. It was surreal to be staring at the corpse of Vladimir Lenin, dead nearly a century. He was felled at the young age of 53 in 1924 by a series of massive strokes, and although he asked to be buried next to his mother in St. Petersburg (renamed Leningrad the year he died, changed back in 1991 after the USSR imploded), the revolution required his services. Instead, he was embalmed and placed in a glass-sided sarcophagus for perpetual public viewing. He is pale and waxy looking, although the millions of roubles (13 million in 2016) spent on keeping him presentable mean that the only obvious signs of decomposition are browning fingernails. An electric pump was even installed inside his body to maintain constant humidity. Lenin’s body has lasted longer than the Soviet Union.

His vast crimes have been well known for decades, but the guards posted around his tomb—I counted eight of them—demanded the utmost respect from visitors. The faintest of whispers, and we were hushed fiercely. When Joseph Stalin, whose butcher’s bill far exceeded that of his mentor, died in 1953, his body was also embalmed over a process of several months and laid out next to Lenin until October 1961. When Nikita Khrushchev began the process of de-Stalinization, it was decided that the de-canonized killer had to be posthumously dethroned. He was hastily buried a couple of hundred feet away late one night in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis. His brutalized subjects still remember him fondly—when I walked past, Stalin’s grave was the only one heaped with fresh flowers. Stockholm Syndrome is particularly potent in Moscow.

Under Boris Yeltsin there was some discussion about closing the Tomb and burying Lenin next to his mother in St. Petersburg’s Volkov Cemetery, and the Russian Orthodox Church supported the proposal. It was Yeltsin’s successor Vladimir Putin who opposed and reversed the decision. Putin, too, needed Lenin’s services, this time for reconstructing the rubble of the Russian identity crushed by the collapse of the Soviet Union. To bury Lenin, Putin believed, would be to imply that the Russian people had followed false gods for seventy years. Putin may be positioning himself as the champion of a nationalized Russian Orthodoxy, but he is also the protector of their persecutor’s legacy. In the forest where Lenin hid that long summer of 1917 in a makeshift wigwam writing The State and the Revolution is a little museum and a facsimile of the original structure. All of it, a Russian guide told me with an ironic smile, is funded by Putin.

Lenin’s Mausoleum, of course, has also been the main stage of Russian history throughout the 20th century. Designed by Alexey Shchusev, the granite tomb incorporates elements from the Step Pyramid, the Temple of the Inscriptions, and the Tomb of Cyrus the Great. Atop the tomb Russian leaders viewed the endless Cold War parades showcasing the flexing of Soviet military muscle; Dwight D. Eisenhower, Fidel Castro, and Mao Zedong stood alongside their friends and foes; fiery wartime speeches were delivered. Just outside the gates of Red Square, I was at Putin’s anniversary celebration of the annexation of Crimea in 2018 on the eve of his “re-election,” the streets transformed into a sea of flags and ringing with the nationalist anthems of Russian pop stars. Separated from the crowd by a line of fur-hatted guards, Putin himself was a mere hundred yards away. History has not ended yet.

It is an irony that the regimes of godless Communists and imperial thugs must preserve the corpses of their revolutionary leaders, made incorruptible by enormous amounts of money, for their subjects to worship. Mao and Lenin, after all, did not want to be put into showcases. Mao wanted cremation, and Lenin wanted to lie next to his mother. But they are needed as figureheads—or frail support beams—for an entire belief system, and so their wishes were overruled and their corpses are placed in public so people can perform masochistic acts of worship to some of history’s greatest mass murderers.