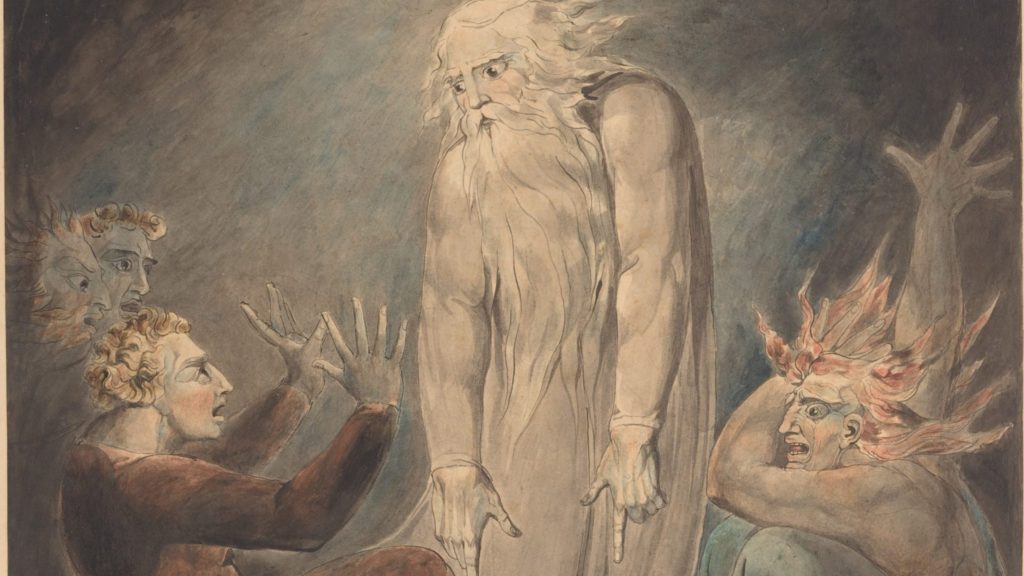

“The Ghost of Samuel Appearing to Saul” (ca. 1800), a 32 x 34.4 cm pen and ink with watercolor over graphite by William Blake (1757-1827).

In reading Andrew Klavan’s Truth and Beauty, of which there are many positive things to say, I came across the following passage. In one sense, it is typical of a certain strand of American Protestant exegetes, transgressing on the Bible with liberal republican presuppositions:

There was a time in the distant past when the people of Israel lived without rulers … But when the prophets became corrupt, the people demanded a king … The prophet Samuel warned them what governments do: how they make servants of the people and tax the best of their goods … To me, it seems like a second fall from a second Eden. They strayed away from freedom and stepped into the cycle of history.

Of course, Israel had not been living “without rulers” at the time of Samuel’s warning. From Abraham to Moses and Joshua, and Samuel himself, there had very obviously been rulers. The term “government” is also wholly inappropriate, as Deuteronomy clearly articulates governing institutions. But perhaps what is most jarring of this paragraph (which, thankfully, is not characteristic of Klavan’s book), is the idea that Israel had hitherto enjoyed freedom, and was only now entering the cycle of history. To the contrary, Israelites had, by now, endured the very opposite of freedom, having been slaves in Egypt. And, certainly, one could not hope for a clearer account of historical mutability, nor one more removed from the idea of Edenic stability, than Exodus and the entry into a promised land where the Israelites would wage war under Joshua.

But even beyond these inaccuracies, possibly owed to rhetorical hyperbole in the service of a greater point, the anti-monarchical reading of 1 Samuel 8:9-11 (which is the warning Klavan is referring to) hides an important lesson. Namely, what the Biblical understanding of kingship is, and when it is appropriate (incidentally, I recommend this discussion on the Biblical teaching on monarchy).

Says the Lord to Samuel concerning the king Israel is requesting:

Now therefore hearken unto their voice: howbeit yet protest solemnly unto them, and shew them the manner of the king that shall reign over them.” And Samuel told all the words of the Lord unto the people that asked of him a king. And he said, “This will be the manner of the king that shall reign over you: He will take your sons, and appoint them for himself, for his chariots, and to be his horsemen; and some shall run before his chariots.

Crucially, 1 Samuel 8:11 parallels another scripture, Deuteronomy 17:16-17, which lists the excesses that the king Israel will abstain from:

But he shall not multiply horses to himself, nor cause the people to return to Egypt, to the end that he should multiply horses … Neither shall he multiply wives to himself … neither shall he greatly multiply to himself silver and gold.”

The difference between these passages from Deuteronomy and Samuel is that the former provides instructions on how to receive a righteous king, whereas the latter provides a curse for failing to follow this instruction:

When thou art come unto the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee, and shalt possess it, and shalt dwell therein, and shalt say, I will set a king over me, like as all the nations that are about me; Thou shalt in any wise set him king over thee, whom the Lord thy God shall choose. (Deuteronomy 17:14-15)

Deuteronomy commands that kings be appointed after possessing the land. However, Samuel’s insistence that Saul did not keep the Lord’s command to defeat the Amalekites (1 Samuel 15) suggests that the land had not been fully conquered at the time of his coronation. Even after the rise of Saul and his initial campaigns, then, it seems the conditions for receiving a king specified in Deuteronomy 17 had not been met.

Samuel would have been condemning the desire to appoint a king before conquest is complete. The prophet’s warning would therefore concern the specific king Israel was to receive after asking for one at the wrong time—namely Saul—not monarchy in general.

Israel’s fault appears to be demanding a king before the appointed time.

Importantly, this is consistent with the rest of the Bible. Discernment between good and evil is frequently connected to maturity, and often specifically to the exercise of judicial authority on the part of kings (1 Kings 3:9, Isaiah 7:15, etc.). Christ, however, refuses to exercise judgement, and to accept the kingdoms of the earth when these are offered by the devil. His kingship manifests through this abstention. We are thereby led to understand that Adam and Eve would likewise have received proper dominion had they abstained from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil first.

In the Bible, then, kingship (or its proper exercise) is the fruit of an initial phase of abstention and labour.

The root of Israel’s mistake in requesting a king is faithlessness: Israel wants a king before the time is right because they are facing ongoing threats and do not trust the Lord’s promise according to which these will ultimately be overcome.

They want a visible, outward sign to project power for them and in which to put their faith. Furthermore, we are told that Israel’s faithlessness runs so deep that they are engaging in idolatry and not keeping the commandments.

The fact that the kind of monarchy Israel desires in 1 Samuel, and which leads to the anointing of Saul, is not the kind of monarchy prepared for them in Deuteronomy, is emphasised by the desire to have a visible, warrior king in which to trust:

The people refused to listen to Samuel. “No!” they said. “We want a king over us. Then we will be like all the other nations, with a king to lead us and to go out before us and fight our battles.” (1 Samuel 8:19-20)

Deuteronomy 17 does not refer to the king fighting battles for Israel; more specifically, it does refer to his not acquiring a great number of horses for himself, to which Samuel seems to provide a contrast, warning that the king Israel will get will precisely build up an army: “He will take your sons, and appoint them for himself, for his chariots, and to be his horsemen; and some shall run before his chariots.”

It appears, then, that Israel’s battles were to be fought, and her possession of the promised land was to be secured, without a standing army, but through what we might describe as free, popular militias. The kind of monarchy of which Deuteronomy 17 speaks abstains from forming a permanent standing army, or at least a large one.

Once such a structure is brought about, it tends to justify itself by pursuing conflict, and to orient the wider economy towards its own maintenance.

That kingship as such is not being rejected may also be argued by pointing out that, by the time of Samuel, Israel had already been organised under a prophet-king in the person of Moses: “Moses commanded us a law, even the inheritance of the congregation of Jacob. And he was king in Jeshurun, when the heads of the people and the tribes of Israel were gathered together” (Deuteronomy 33:4-5). Prominent Jewish commentators such as Philo of Alexandria have emphasised the kingship of Moses, with Maimonides and the Targums, together with the majority opinion within Christian tradition, defending monarchy as divinely instituted.

Indeed, for his part, Samuel provides a prayer for the divinely-chosen king:

The adversaries of the Lord shall be broken to pieces; out of heaven shall he thunder upon them: the Lord shall judge the ends of the earth; and he shall give strength unto his king, and exalt the horn of his anointed (1 Samuel 2:10).

We may also refer to injunctions to obey kings (Ecclesiastes 8:2-5, Proverbs 24:21-22).

In addition, we should recall that kingship is the paradigm of the messianic age in Old Testament prophecy (Genesis 49, Numbers 24), so that, in the Gospel, Christ’s authority is described in terms of Davidic kingship. This messianic authority does not abrogate political institutions and their heads. Rather, it is a source of kingship among the faithful: … “and the kings of the earth do bring their glory and honour into it” (Revelation 21:24).

The fact that there is to be no earthly king in course of conquest, so that kingship is exercised by the Lord during this period, tells us that

1) Oppression results from the founding of institutions in a state of faithlessness (Israel was worshipping idols), which is to say, of fear (idols are sacrificed to in order to vouchsafe favour against a chaotic world, the same spirit in which Israel desired a king to fight its battles). This principle applies to the individual personality: developing character traits out of defensiveness and underlying fears will produce psychic tyrants. Political initiatives based on the urgency of a crisis perpetuate the crisis; what we do out of fear will endure in fear.

2) The human manifestation or expression of certain principles, like righteous authority, is to come as fruit of the labour that creates the proper context for their exercise (in this case, the subduing of the land over which the king is to rule).

3) Proper manifestation (in this case, political articulation) is to follow a period of suspense, in which action is undergone without a particular manifest centre of action (analogous to conquering without having a king), but in a spirit of faith in the un-manifested divine source (analogous to trusting in the promise that the land has been appointed to Israel). We are required to walk in faith, lacking external encouragement, before entering into a new context and receiving formal stability.

We can therefore describe the proper manifestation of principles through external forms (like the institution of monarchy) as a Sabbatical rest: Deuteronomy 17’s instruction to appoint a king after the conquest of the land is analogous to the Lord’s rest after the creation of the earth in Genesis.

Following the threefold phases of glorification in Christian tradition (katharsis, theoria, theosis, explored in the essay The Imperial Ideal and Multipolarity), we first experience mortification, removing ourselves from a particular context or habit (leaving Egypt and wandering in the desert); then we experience a vision of transcendence, understanding the underlying principles of reality (gaining victory, subduing the land in a state of faith in the transcendent), and; finally, we possess a new set of particulars, a new context, being able to inhabit that new context without turning it into an idol, because we have been trained by the previous phase to abstain from putting our faith in externals (this corresponds to Davidic monarchy over a united kingdom).

If this order of things is not respected, the result is like a person who claims the wisdom of a saintly teacher prior to having actually engaged in ascetical discipline. Politically, the king will base his authority on conquest, having participated in it, and so the exercise of governance and the need to conquer will become conflated, and legitimacy will be sought through continued violence.

Because we did not experience the suspension of external support and the trial of walking by faith, turning to the transcendent source, we will continue to ascribe our losses or victories to external causes. Furthermore, and more subtly, the king who is not aware of the transcendent principles that manifest political institutions will fail to distinguish between the two: he will identify his laws with justice as such, his people with humanity as such, and so on. He will therefore fall short of the universal in-gathering of the nations for which Biblical prophets were preparing Davidic monarchy (from Isaiah’s blessing on the enemy nations of Egypt and Assyria, to John’s Revelation).

There is a great deal more that deserves to be said on this topic. Specifically, in order to properly understand the instruction to abstain from demanding a king before the land is subdued, we need to turn to the Gospel and the injunction to “turn the other cheek.” This instruction (Matthew 5:38-40), which occurs in the Old Testament as well (Lamentations 3:25-66) contains both a personal and political lesson. The political context of Jeremiah’s Lamentations is the same as that of the Gospel: foreign oppression and the destruction of the Jerusalem temple (prophesied by Jesus in Luke 21).

I want to suggest that overcoming present conditions is analogous both to the conquest of the promised land and surviving the destruction of Jerusalem. Conquest without first appointing a king and resistance by turning the other cheek are equivalent. The spiritual state cultivated by relinquishing pride and the contestation of insults (as recommended in Matthew 5) is that state which we receive when we act without anticipating the fruit of our labour (kingship), in a spirit of faith bereft, for the time being, of external, stabilising forms (as recommended by Deuteronomy 17).

We may finish by drawing a few more or less practical lessons from the above, such as:

1) To avoid confrontation with the powers that be over personal pride or reputation, as this pollutes any struggle and hopelessly embroils us;

2) Not to undergo political renewal by articulating political institutions in a time of crisis, as the fear and urgency of that crisis will become the legitimising narrative of those institutions, thereby perpetuating the crisis;

3) To establish communities capable of surviving the “encompassing armies” (civil discord), famines (unstable supply chains), and other scourges referred to in Luke 21, characteristic of times of crisis;

4) To keep the commandments, tending to the poor (widows and orphans are constantly mentioned in scripture) and abstain from idolatry (that is, from making irrational sacrifices out of fear of a chaotic world).