The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

There are certain people who love dogs even after being bitten by one. I myself have a similar tendency, albeit not towards dogs, but towards philosophers and artists who themselves deviate particularly harshly or brutally from my own beliefs. This is certainly true about Diego Rivera (1886-1957), Mexico’s greatest painter.

Despite my love for his oeuvre and my interest in its subjects, writing about Diego Rivera is far from an easy task; it necessitates discussing everything from the ideology of Marxism and the nation of Mexico to the person of Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) and the politicization of life. Perhaps most interestingly, confronting Diego Rivera’s life and work means considering how art, religion, and politics can become intertwined, and what the lasting impact of this marriage was.

While Rivera is often overshadowed today by his association with his wife, Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, it is important to acknowledge his remarkable stature as Latin America’s most influential artist during his time. Despite our different political views—Rivera as an ardent Marxist and myself as a conservative—the profound influence he had in shaping the political landscape of his country is particularly inspirational for me.

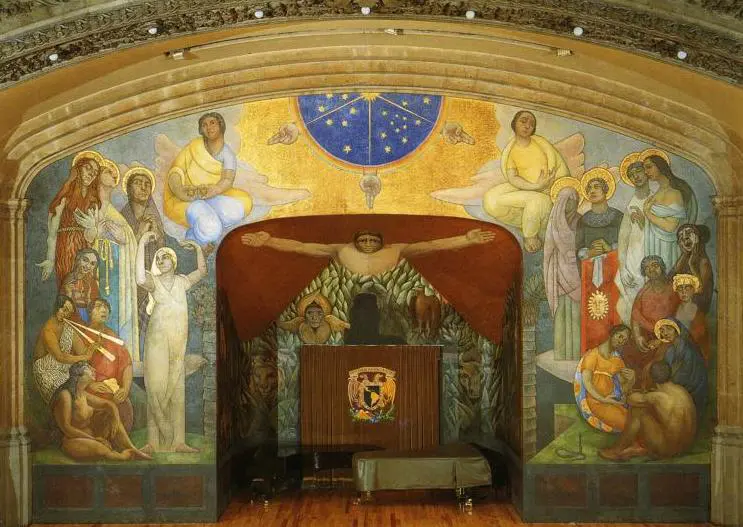

Rivera’s artistic contributions went beyond the realm of art itself; his murals became powerful vehicles for political expression and social commentary. Although our political perspectives may diverge, it is undeniable that Rivera’s artistic legacy left an enduring mark on the cultural and political dynamics of his era. A key work for understanding this influence is “La Creación,” in which Rivera transforms The Divine Creation into a political instrument.

Rivera was a highly acclaimed artist who played a significant role in Mexican art history. Alongside Kahlo, Rivera gained fame for promoting Mexican art in Europe and the United States. After traveling across Europe and being influenced by artists like Amedeo Modigliani and Pablo Picasso, Rivera returned to Mexico at the age of 34, driven by financial constraints and the desire for recognition within his own community. From 1921 onwards, Rivera dedicated himself to creating impressive murals, known as pinturas murales, commissioned by wealthy Mexican and American patrons.

Rivera was not alone in this artistic evolution. Other prominent Mexican artists such as Orozco, Siqueiros, and Guerrero also began creating colossal frescoes. Together, they developed an avant-garde Latin American visual language that stood on its own, completely distinct from the imitation of European styles. This marked the birth of the Muralism movement in Mexico, which gained significant traction in the early 1920s.

Muralism arose during a time when Mexico was recovering from the trauma of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917). This left the country in a fragile economic state and deeply divided on social issues. The search for a post-revolutionary identity became apparent in various artistic expressions, including Muralism. While each artist within the movement emphasized different aspects, common themes such as the revolution itself, the working class, the indigenous population, and socialism all played a central role.

Rivera infused his murals with political ideals and references. However, reducing his murals to mere Marxist propaganda would overlook the complexity and nuance of his visual language. Rivera’s pinturas murales were intricate and layered, incorporating historical and political allusions, hidden messages, and intimate elements. “La Creación,” to which we now turn, is a stand-out example.

Created between 1921 and 1923 at the Auditorio Simón Bolívar, “La Creación” holds a significant place in Rivera’s career as a muralist. Rivera drew inspiration from European masters, particularly Raphael’s fresco “The Trinity and the Saints” (1505-1521), while also infusing traditional Mexican elements. The figures in the mural are vibrant, with tanned skin, and their hands and feet are often depicted as larger than usual, symbolizing the laborious lives of peasants in the fields, a stylistic element we often see in other paintings of rural life too, such as in Flemish Expressionism. The angels portrayed are indigenous men and women, possessing sturdy appearances while still emanating a spiritual and mythical aura through their colorful robes and halos.

In this mural, Rivera presents a Mexican creation story, liberated from the pervasive European and colonial influences that had previously dominated Latin American art. The moment of creation is depicted powerfully, with a divine figure opening its arms and setting the world in motion. The mural’s harmony and use of color convey the notion that the created world is superior to what preceded it. Rivera deliberately chose symbolic imagery to convey his message. To grasp how Rivera utilized Divine Creation as a political tool, one must explore the philosophical interplay between the two concepts.

A moment of creation is inherently a moment in time, with a before and an after. However, the time before Divine Creation is depicted as empty, characterized by darkness. The book of Genesis describes the biblical creation as a process where God separates light from darkness, ultimately leading to the formation of the world. This teleological framework of creation, with a purposeful and linear time frame, contains an inherent eschatological element—an anticipation of a finality to which everything will ultimately return. This eschatological and teleological thinking can extend beyond theology. Indeed, it has found resonance in political and revolutionary thought throughout history.

Similar teleological thinking emerged in Marxism, of which Rivera was a staunch supporter. According to Marx, the fulfillment of socio-economic revolutions, such as communism, is always preceded by certain conditions of possibility. They do not happen ‘suddenly’ or ‘just like that,’ but are always reactive, and thus causally determined. This assumes a historical determinism often referred to as ‘historical materialism.’ Reaching the historical stage known as ‘communism’ is not possible without first passing through the stage of capitalism. Rivera believed that a new and better world would eventually emerge from the darkness produced by capitalism, drawing parallels to the moment of Divine Creation.

While Divine Creation itself is not a political event, Rivera assigned it a political role. “La Creación” signifies more than a mere analogy or metaphor; it represents a pivotal moment in art and society. The mural reflects the emergence of an era where art and socio-political themes intertwined seamlessly. Rivera deliberately chose the moment of creation as a subject matter, recognizing its revolutionary potential. Each moment of creation signifies a separation, be it of matter, time, forms, molecules, colors, or meanings. Through these moments of separation, Rivera aimed to articulate a new political world that transcended his artistic ambitions.

Rivera’s intentions were evident in his choice of imagery, medium, and locations. The grand scale of murals, displayed in auditoriums, railway stations, and the Palacio Nacional, lent themselves to a socially dynamising purpose, far beyond the reach of traditional art galleries or museums.

Gradually, Rivera imbued the moment of Divine Creation with a radically new image. In this image, theology and mysticism served the cause of immanent political ideals. It represented the metaphysics of a new era in Mexican Muralism—a time when artists reconnected with their roots, while addressing social reality and political life. Rivera’s artistic and political intentions were clear, as he proclaimed:

For the first time in the history of art, the humble masses, the crowd, the workers and peasants, the man in the street, in the factory, in the furrow: the mass … appears as the main hero in art. That is what we did [and] what no one had done before us: this is our glory.

However, in this revolutionary Marxist message, there seems to exist a profound conservatism as well—a longing for an original Latin American life that prioritizes family, honor, and community. In making this observation,, I am treading on particularly thin ice. For the avoidance of doubt, trying to portray one of the best-known Marxist artists as a ‘conservative’ pure and simple is a sin against historical truth in which I have no desire to indulge. Rivera is as much a conservative as Saint Anselm of Canterbury was an atheist or Arthur Schopenhauer a Catholic theologian.

But that does not mean one can and should not view Saint Anselm’s philosophy through an atheist lens. It is true that his philosophy cannot be understood apart from his belief in the Triune God of Christianity, but approaching his works without sharing this belief opens up certain questions, leading to a more complex understanding of his philosophy. The same applies to Rivera and his art. Highlighting the less quintessentially Marxist aspects of his work, and how they function within his major social crusade, adds a layer of complexity to his work, and presents a view that is not commonly taken on his oeuvre. Because his art was so characteristically intertwined with his communist commitment—to the point where he had made politics and art each other’s medium—there seems to be only one strongly defined way to interpret Rivera’s oeuvre. Yet anyone who makes an attempt to question these interpretations will find ambiguities and intricacies in Rivera where at first glance there do not seem to be any.

What is indisputable, however, is that Rivera’s contributions to art and society extend beyond his artistic achievements. This is the point, however, at which many conservatives raise the question of whether an artist should engage with political or shocking themes at all, renouncing what we would describe as beauty and harmony, which in the eyes of most conservatives is the ultimate purpose of artistic expression. English philosopher Sir Roger Scruton (1944-2020) would answer this question in the negative, and I am inclined to do the same, but that does not diminish the historical impact that Rivera’s oeuvre has had on Latin American art and society. His murals, particularly “La Creación,” embody the interplay between politics, history, and religion. They signify a transformative moment where art transcends its traditional boundaries, and social and political themes become integral to artistic expression. And that, too, is his glory.