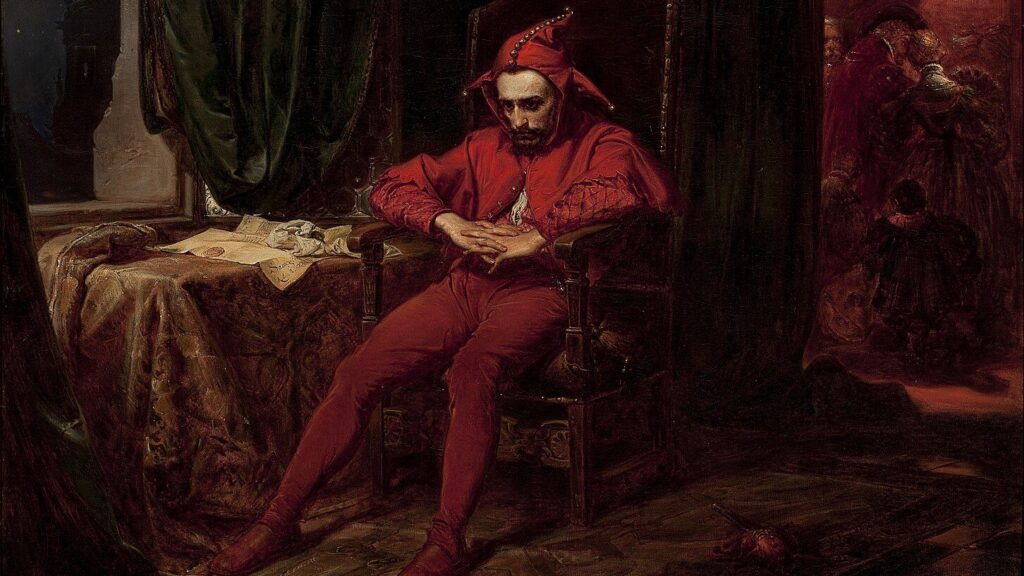

Stańczyk (1862), a 88 x 120 cm oil on canvas by Jan Matejko (1838-1893), located in the National Museum in Warsaw, Poland.

As soon as he’s digested his last crumbs of foie gras, topped up with a drop of Sauternes, Monbazillac or vin jaune, which have enabled him to get through the New Year merrily, the gourmet who has the bad idea of reading the press or social media is bombarded with peremptory advice on the need to start a ‘dry January.’ This month’s diet is to make up for the gastronomic excesses he indulged in between Christmas and New Year’s Day—sorry, during the ‘end-of-year festivities,’ so as not to offend any sensibilities.

The injunction to drought at the start of the year comes from Great Britain. The campaign was first launched in 2013 by Alcohol Concern (now called Alcohol Change UK) and celebrated its tenth anniversary in 2023. Before conquering the UK, this mania was suggested in 2008 by an Italian-American, Frank Posillico, who went on a diet after a few days of drinking and subsequently boasted of the merits of this drastic abstinence, which enabled him to shed a few unwanted kilos. If we go back a little further, we find in the genealogy of this ritual for bored middle-class society a certain John Ore, who challenged himself to an alcohol-free January in 2006, calling it “drynuary.”

Over the years, the campaign has grown in popularity to the point where, according to the official British website, 130,000 people will have signed up by 2022. On the other side of the Channel, the trend has finally caught on, and it’s now high time in France to extol the virtues of Dry January in imitation of our so-called best enemies. One Frenchman in ten is said to have adopted this sad asceticism. Germany and Switzerland have joined the movement and have in turn founded their own local clubs of temporarily repentant drinkers. Some will say that it is not the least paradoxical that the concept of drought has been extended geographically by the British.

Dry January thus joins the cohort of social practices recommended by the progressive virtue leagues working relentlessly to establish a safe, green world as sad as a rainy day. John Ore explains that his approach was inspired by Lent, the period of dietary restrictions, fasting, and abstinence that Christians practise during the forty days preceding Easter, in memory of the forty days Christ spent in penitence in the desert, or the forty years the chosen people spent crossing the desert after leaving Egypt following Moses. This is no coincidence. Our friend Chesterton would tell you in his wisdom that our modern world is full of ancient Christian virtues gone mad. Dry January is a perfect illustration of this.

Western society has happily rid itself of a whole raft of moralistic rules that were cruelly impeding its happiness here on earth. These rules used to be laid down by the churches, which were notorious for being backward-looking institutions designed to restrict human beings and hinder their free development. Fortunately, modernity has made it possible to break the chains forged by centuries of obscurantism.

Today, (Western) man knows that all this childishness was only intended to fatten a corrupt clergy with little concern for the happiness of others. He is free. He’s free, but he’s bored and sometimes finds, after placing his 89th order on Amazon in a fortnight and wolfing down another tray of fusion food, that his life lacks a little meaning and a spirit of sacrifice. So he’s invented some new rules to spice up his sushi a bit—rules that will give him the feeling that he’s still in control of his existence and that he knows how to escape the grip of invasive consumerism. Dry January will allow him to abstain from alcohol for a month. For a good cause, of course. Lent is communitarian and obscurantist, but Dry January is ecological, healthy, and responsible. Once he’s finished his Dry January, he’ll set himself a new challenge: Green Monday. This time, the sacrifice won’t be for the waistline or cholesterol levels, but for the planet. It’s like the Friday of Lent, a day without meat, except that it’s on Monday and not Friday—it’s details like that that measure a person’s true freedom, isn’t it?

Enough jokes. We no longer open a missal, we cover our ears so that we don’t have to listen to the priest, but we blindly follow the injunctions laid down by those we call ‘influencers.’ We sometimes accept from them a degree of interference in our private lives and daily routines that we would never have tolerated from the priest.

It’s fascinating to see the extent to which our contemporary society cultivates a good conscience, destroys the legacy of past wisdom, claims to be emancipated, but becomes entangled in a web of small, mediocre regulations that, when all is said and done, simply ape the standards of yore, without adding any grandeur, panache, or transcendence. Dry January is a challenge with TikTok or Facebook as its field of honour. Limited in time, it claims to change the body, but never tackles the soul. And for good reason: the prevailing materialism has no use for souls. The followers of Green Monday are self-satisfied in their petty living room but have no intention of building anything. It will no doubt have escaped these new censors that the same civilisation that advocated fasting and abstinence on Fridays, during Advent and Lent, is the same one that has covered Europe with vineyards—with no contradiction other than apparent. Wine delights the heart and soul and has the eminent dignity of having been chosen to become the blood of Christ, but to abuse it is a sin that debases. This fine dialectic, polished over the centuries, is the nobility of the Christian religion, which knows the weaknesses of man but knows how to sublimate them by the strength of divine virtue. In France, when we raise our glasses in a toast, the traditional expression is “To your health!” (A votre santé!) Proof that a good glass is the best antidote against all the ills of life. Fans of Dry January, a pitiful Lent for non-believers, don’t know what they’re missing. Too bad for them.