Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

At this time of year in Britain, shops are full of merchandise for Hallowe’en: plastic orange pumpkins, plastic cauldrons, wizards’ capes, witches’ hats, spiders’ webs. All are mass-produced and sold in millions each year. Hallowe’en is, for most people, merely another entry in the liturgical calendar of materialism: a time to buy themed pieces of plastic and sugar and have a party. On the other hand, growing numbers of pagans are attempting to make All Hallows’ Eve something pre-Christian and dark, while many evangelical churches are denouncing Hallowe’en itself as pagan, attempting to supplant it with ‘Light Parties.’

Sadly, everyone seems to have forgotten the original, Christian spirit of All Hallows’ Eve, and the meaning of its traditional macabre customs. In this brief essay, I want to consider both and to suggest that the ancient customs of Hallowe’en have much to offer us conservatives today.

First, let’s turn to the pre-history of Hallowe’en. Before the advent of the Church, Gaelic pagans reckoned the night of the 31st the end of the harvest season and the beginning of the festival day of Samhain. Samhain was a liminal time when the boundaries between the natural and the unnatural, the dead and the living, grew porous. One had to be on one’s guard against evil forces. Bonfires were lit for protection and cleansing, food and drink was offered to appease the fairies, divination was practised, and families set places at table for the souls of any dead relatives that chose to visit.

The expanding Church saw some good aspects in these pagan customs: salutary reflection on death, wariness of dark powers, and the quixotic, distinctively human defiance of holding a feast just as the darkness set in. For these reasons, the Church took Samhain and ‘baptised’ it. By the 9th century, the 1st of November had in Britain and Ireland become All Hallows’ Day—in modern English, All Saints’ Day. This feast echoed the noble defiance of Samhain, but perfected it with a new Christian confidence and hope in Him who conquered death and darkness.

This Christian confidence made it unnecessary to appease ill spirits, and so in the official Christian liturgies the apotropaic magic of Samhain was abolished. Yet the eve of All Hallows, like the eve of Samhain, remained a time for reflection upon death and evil. In parts of England and Wales, children would go ‘souling’: they visited houses with turnip lanterns that represented souls in purgatory, and prayed for the souls of the occupants of the houses in return for solemn-looking white ‘soul cakes.’ Hallowe’en retained its character even after the new All Souls’ Day had spread through the church in the 10th century.

We can best understand the original, Christian spirit of Hallowe’en by looking to the mediaeval legend of the Danse Macabre (from which the English and French adjective macabre derives). According to popular belief, the souls in purgatory became restless on Hallowe’en and rose from their graveyards to console themselves with a nocturnal dance. Though it had no part in official Christian doctrine, the idea of the danse was taken up by ecclesiastics and depictions of it were installed in mediaeval churches great and small. These depictions showed newly dead people of all classes dressed in their best clothes and dancing hand-in-hand with figures of Death.

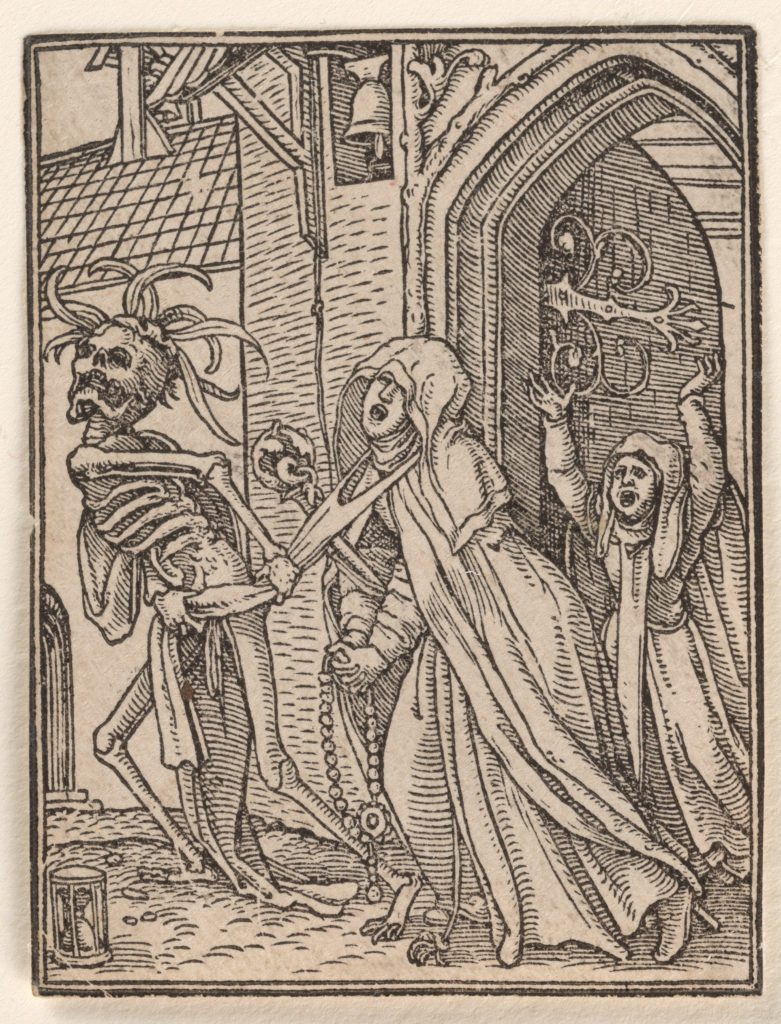

If today one tries to imagine the Danse Macabre, one may well call to mind the famous Dance of Death woodcuts by Hans Holbein the Younger. These seem to reflect a glee in the details of the death and suffering of popes, abbesses, and priests. They have influenced our conception of the macabre ever since they were first printed in Lyons in 1538, making us think of the macabre as a morbid and despondent thing.

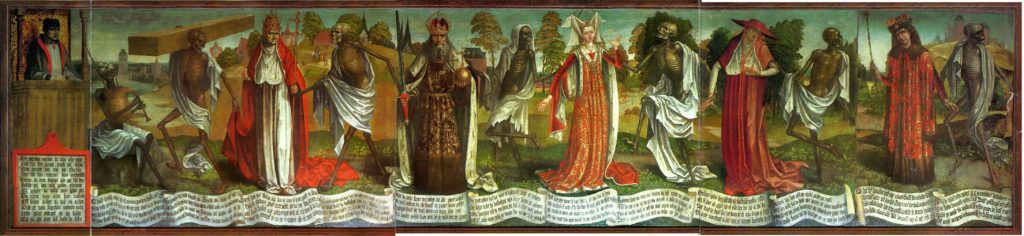

But Holbein’s works were not true reflections of the mediaeval spirit of Hallowe’en. Look instead at the surviving left portion of the 15th century Danse Macabre by Bernt Notke at St Nicholas’ Church, Tallinn. In this work, a preacher addresses viewers whilst various representations of Death each lead away a dead person. Beneath each figure is a dialogue caption; the dialogue is similar to other 15th century ones found in Lübeck, Paris, and Spain.

Notke’s Danse is wryly comic, not dark. Just look at central Death between the empress and the cardinal! He could be the lead singer in a jazz club. Look too at the awkward, bashful cardinal himself, averting his eyes from the empress. He looks as if he is more comfortable in scholastic disputations than at a dance. Look at the empress, slightly swaying to the tune, while trying to retain her offended dignity (‘I believed that I had great power, but of death I never thought,” reads the caption).

Meanwhile the first Death on the left, a bagpiper, leads the tune. He looks like a wizened old fakir, and his keen sedentary contribution makes the other Deaths seem all the more frenetic. Beside him the pope suppresses a grin. He is able to catch the consoling rhythm of the Danse because he is humble enough to accept its absurdity and his own (“I must here and now become a handful of earth … let this be an example to you who will be pope after me”). Only the Emperor is a thoroughgoing party-pooper. He is still clinging on to the insignia of his temporal power. Death horrifies him: “O death, you ugly figure, you completely change my nature … you come, horrible apparition, to make worm feed of me.” Just look at his pose: He thinks that he is God.

Note those telling words “you completely change my nature.” The Emperor is deluding himself, forgetting that his nature was always a mortal one even when he was most powerful. Hence he of all the figures finds death most disgusting and terrifying. Death rebukes him for this: ‘“haughtiness has blinded you, you didn’t know yourself.” We will return to this idea below.

What then is the meaning of all this dancing? In short, the Danse enjoins humility. Its unsqueamish depiction of the physical facts of death forces the viewer to confront his own mortality, remembering that he is but dust, however exalted he is in this world. But ultimately the work is hopeful. The dead souls are, one assumes, trapped in purgatory; thanks to the mercy of God, they will one day be free of pride and able to join the perfect dance of heaven. In their present condition, they are to be pitied not feared. For as the preacher says, “if we do good deeds we can be together with God. We will get the reward we justly deserve.”

These Christian ideas and this aesthetic together form the true and original macabre. Rightly understood, the macabre reminds us that we are limited creatures who will soon be dust, and that our sinful human pride is therefore absurd. It thus helps us not to fear the forces of darkness, but to remember that their war against God is foolish and premised on a wilful blindness to their creaturely limitations. The macabre is to be distinguished from the morbid, which is a perverse fascination with death and which tends towards an appeasement and then a worship of the powers of darkness.

Sadly, most Christians and conservatives have forgotten the distinction between the macabre and the morbid. I believe that this is regrettable, because a small dose of the macabre—such as Christians used to take at Hallowe’en—is a potent tonic against the delusions of late modern liberalism and their disastrous effects.

Consider first the progressive liberal’s attitude to death. The essence of progressive liberalism is the rejection of givenness: of all unchosen impositions upon the individual, from the cultures and customs in which he was brought up, to his human nature itself, with the physical and emotional limitations that it imposes upon him. The committed progressive liberal wants to reject customs and norms that he finds restrictive and to determine his own nature. If this causes any emotional or physical damage to him or others, he only resents the moral laws written into human nature as merely internalised structures of oppression. He thinks that they can be overcome by human choice and human knowledge.

Unfortunately for the progressive liberal, there is one final objective fact of human nature that no one can deny. It is death. Death is the one brute fact that proves that we cannot construct our own natures. Hence every progressive liberal must, on some level, close his eyes to death. He must be pridefully blind to his mortality, just like the Emperor in Notke’s Danse.

This self-delusion about death has long influenced Western culture and Western politics. We can see it especially clearly within today’s American Democratic Party, one of the most consistently progressive-liberal parties in the world. Most obviously, Joe Biden is a senile man pretending to be healthy. Similarly John Fetterman, who has sadly suffered brain damage after a stroke, is now a Democratic candidate for the United States Senate, despite the fact that he struggles to understand some questions without the aid of a closed-caption machine.

Here we confront an illuminating paradox. Progressive liberals, like those in the Democratic Party, close their eyes to objective human limits and death. It is hard to imagine them appreciating the humble honesty of the Danse Macabre. Yet ironically, the party today is itself increasingly ghoulish. One must feel compassion for Joe Biden. But he does not belong in national politics, and those who are keeping him there for their own convenience have created a spectacle that is ghoulish. It is not his cognitive decline itself that is the problem; that is a natural part of human life. The problem is that he is rolled out each day, puppet-like, to perform a wholly inappropriate role.

The conceit is simply creepy. On the other hand, while these Democratic leaders seem to be in denial of human limits and mortality, the party has become a cult of death, celebrating abortion as a means of liberation and encouraging the sterilization and maiming of confused children. The entire party now has something of the night about it.

We can now perceive the forgotten value of the macabre. It teaches us the first lesson of conservatism: that we will all die, and that we must therefore acknowledge our creaturely limits. It also gives us confidence and hope, reminding us that the darkness of the world is ultimately absurd and not to be feared, because it flows from an obviously futile rebellion against the created order. On the other hand, when a society forgets the macabre and tries to close its eyes to death, it soon embodies the very ghoulishness that the Danse warns us against.

For this reason, let me raise my voice in favour of the salutary conservative lessons of the traditional Hallowe’en macabre: for skeletons and soul lanterns and the legend of the Danse. I know that I will be putting a carved turnip outside my house on Hallowe’en—and perhaps going souling too.