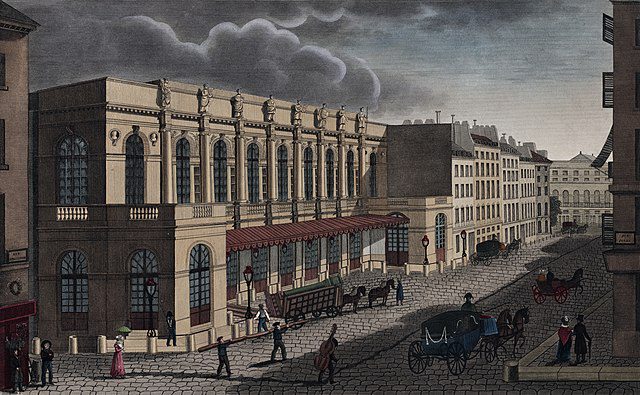

Don Carlo by Francesc Soler i Rovirosa (1836-1900), located at Centre de Documentació i Museu de les Arts Escèniques

Anyway, everyone does what he can; and he will always achieve something, if he writes what he feels and according to what nature suggests. What I find less tolerable is an Italian writing like a German, and a German writing like an Italian. An Italian should write like an Italian, a German like a German. Their natures are too different to be confused with each other. It is true that music is universal, but the people who compose music are different depending on the different countries they were born in. There is no point [arguing about this]: man is, and always will be, shaped by the country in which he lives, and whatever he does, he will never be able to change his nature completely.

(Giuseppe Verdi in conversation with Gino Monaldi, from Il Popolo Romano, No. 45, 15 February 1887.)

Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) had a strained relationship with the Paris Opéra, which he often disparagingly called “the great fashion shop” (“la grande boutique”). While preparing a revival of his Les vêpres siciliennes in 1863, Verdi had left Paris headlong after a painful confrontation with the opera orchestra and its incompetent chief conductor, Pierre Louis Dietsch (1808-1865). Two years earlier, the same Dietsch had also messed up the Paris premiere of Wagner’s Tannhäuser. Although Dietsch had been fired after the incident with Verdi, two years later the latter refused to come to Paris to attend the new version of his Macbeth at the Théâtre Lyrique. In a letter dated the 19th of June 1865 to his French publisher Léon Escudier, Verdi indignantly also rejected Escudier’s suggestion that he should write a new opera for Paris.

But however critical Verdi was of the Opéra’s working methods—he spoke of an oppressive “system” to which the composer’s wishes and ideas were subordinate—he nevertheless allowed himself to be swayed again in December 1865. For almost a year and a half thereafter, his life was entirely devoted to his new French-language opera, titled Don Carlos. On the 14th of May 1866, he reported from Paris that the libretto was completely finished and that he was pleased with it. After a short stay in Italy, Verdi was back in Paris on the 22nd of July, barely leaving the French capital until the world premiere on the 11th of March 1867. How completely Verdi was absorbed in all the preparations and rehearsals is evident from an article that appeared in Le Figaro on the 17th of February 1867. According to the clandestinely sneaked-in journalist, Verdi sat directly opposite chief conductor François-Georges Hainl (1807-1872), like “a kind of Assyrian god” (“comme quelque dieu assyrien”), constantly absorbing and commenting on the smallest details.

The world premiere was not a fiasco, but neither was it a resounding success. According to Verdi, this was partly due to the cast, which he found mediocre, with the exception of baritone Jean-Baptise Faure (1830-1914), the interpreter of the role of Rodrigue, marquis de Posa. Even nowadays, reactions are mixed. Some Verdi fans find the three-and-a-half-hour opera too ‘French,’ too contrived and wordy, and less spontaneous and affecting than earlier, ‘truly Italian’ masterpieces like Il trovatore or La traviata. And everyone agrees that the ending of Don Carlos is implausible and forced. In Dom Karlos, Infant von Spanien, Friedrich Schiller’s tragedy on which the libretto of Don Carlos is based, Philip II eventually delivers his son Carlos to the Inquisition. In the opera, on the other hand, Carlos is rescued at the very last moment by an old monk, who is recognised by his voice as Charles V, Philip II’s father presumed dead and grandfather of Carlos. Francis Toye, a great admirer of Verdi’s music, wrote of that final scene: “The main merit of the last scene is its extreme brevity.”

But even the opera’s greatest critics cannot ignore the fact that Don Carlos contains some absolute highlights, among the best Verdi has ever written. Who is not swept away by the famous scene ‘Elle ne m’aime pas’ (‘she does not love me’) in which Philip II, tormented by insecurity and insomnia, expresses his feeling that there is no love between him and his young wife Elisabeth de Valois? Or, indeed, by the shimmering aria ‘Ô don fatal’ (‘O fatal gift’), in which Princess Eboli curses her own seductive beauty? Or, moreover, by the great scene in which Elisabeth is torn between love and duty, with which the fifth act opens? But equally impressive is Verdi’s exceptional care in Don Carlos for the choruses, orchestration and harmony. Some contemporaries saw this as progress, others as a regrettable genuflection to composers like Meyerbeer and Wagner.

Personally, I think the pitch-black dialogue between Philip II and the 90-year-old, blind Grand Inquisitor is the absolute highlight of the opera. Step by step, the harsh cleric increases the pressure on the pious monarch to hand over not only Carlos to the Inquisition, but also Rodrigue—the only man at court for whom Philip II harbours deep admiration and affection—who sympathises with the Dutch insurgents. “Must the throne then always bow to the altar?” the lonely king finally asks himself defeated and disillusioned. Such scenes were right up Verdi’s alley, who was staunchly anti-clerical and always took sides with the oppressed, whether it was the Italian people or, as in this case, the Dutch fighting for their freedom.

Finally, a word about the different versions of Don Carlos. During the preparations for the world premiere on the 11th of March 1867, Verdi was still constantly tinkering with the score: 505 bars were removed and replaced by 102 new bars. In 1882-83, Verdi produced an abridged and thoroughly revised version in four acts for the Milan revival in 1884. Don Carlos then became Don Carlo, as the opera was sung in Italian in Milan. The first act of the original Paris version was almost completely deleted, except for Carlos’ short aria, which was now given a place in what was originally the second act (‘Io l’ho perduta—Io la vidi e il suo sorriso’).

Deleting the first act—the so-called Fontainebleau act—represents a great loss musically, and also weakens the libretto dramaturgically. After all, in Fontainebleau, Carlos and Elisabeth meet for the first time and fall passionately in love with each other. When Carlos hears that not he, but his father Philip II will marry Elisabeth, his world collapses and he tries to sublimate his impossible love for Elisabeth on Rodrigue’s advice into deep emotional commitment to the desperate freedom struggle of the Dutch. That original first act is thus indispensable to understand the opera’s subsequent development. For that reason, the composer probably agreed for a revival in Modena in 1886, that the Fontainebleau act be restored. It is this Italian-language Modenese version in five acts that is usually performed today, although the original French version also has its outspoken defenders. The various later adaptations, in which Verdi, for instance, replaced the 1867 ballet music with a wonderful orchestral prelude that sounds unmistakably like ‘late’ Verdi, do result in a somewhat hybrid score that stylistically does not always form a convincing whole, but that is a price most music lovers are happy to pay.

Italian conductor Claudio Abbado made the first complete recording of the French-language Don Carlos in 1985, but respected Verdi’s later changes and additions for Milan. Most of the music the composer deleted prior to the 1867 world premiere is included as a separate appendix, as is the ballet music. Minor downside: some singers from the otherwise excellent cast audibly struggle with the pronunciation of French. Italian conductor Carlo Maria Giulini put all his love for Don Carlo into the 1971 recording he conducted (Italian-language version in five acts, on EMI). Herbert von Karajan stuck to the Milan version in four acts in his 1978 recording (EMI). A more monumental recording of Don Carlo has never been made; the Berliner Philharmoniker are in absolute top form. The other side of the coin is that most of the singers in this studio recording, made at the Berliner Philharmonie, often audibly struggle to rise above the massive orchestral sound.