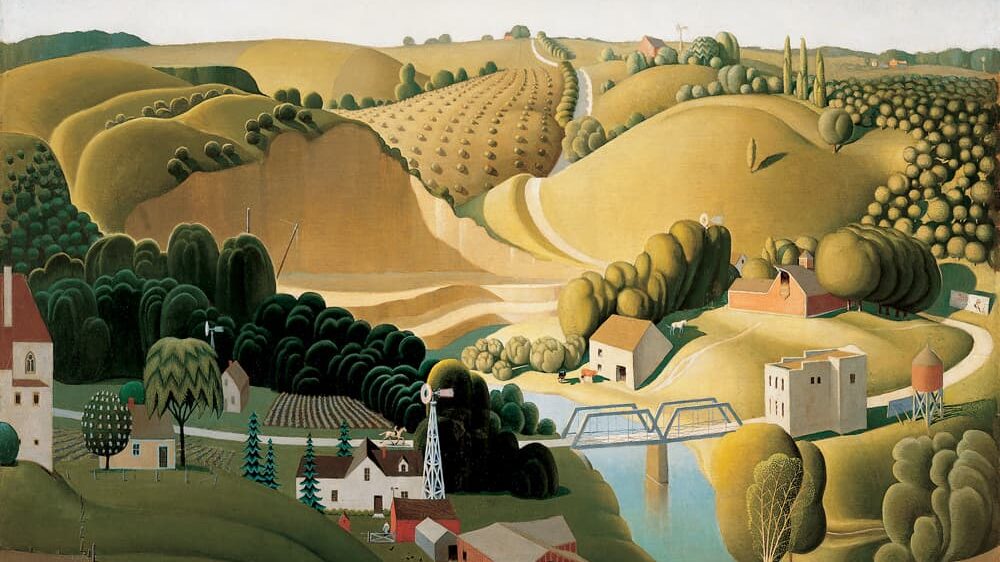

“Stone City, Iowa,” 1930, a 76.8 x 101.6 cm oil on wood panel by Grant Wood (1891-1942), located in the Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, USA.

Glossy, like AI-generated art, Grant Wood’s landscapes—his Spring Turning, with its neon shamrock, moss-shadowed bulbous hills, or his Fall Plowing and Iowan Stone City—offer something AI can’t: the cypher of intention. What did the artist mean?

If they were computer-generated mock-ups of the countryside, a decorative addendum to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City urban planning, the intention would be clear: to sell us on something.

But Wood’s geometrically-precise, smooth-surfaced, neatly warped naturalism has something of the naïveté of peasant art and Mexican murals. It is a record of how things look(ed), but it is also a caricature, whether mocking or idealizing.

The farther we get from topography and agricultural or decorative plant life, the closer we come to a statement. In The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, historical accuracy concerning the American patriot’s 1775 ride to warn local militias of the coming British is beside the point. History is static, as though artificial lights were shining down on a miniature urban model. Our perspective is that of a full-sized person looming over it. Indeed, Revere is riding what was apparently modeled after a toy horse for children, the rider himself being deprived of features.

American Gothic, in contrast, centers the human physiognomy and brings our view level with the painting’s subjects.

A man of vaguely patrician features except for his sullen state and possibly high-strung expression looks out at us, and the likewise elongated face of a woman, about a step behind, looks at, or past, him.

On her neck is a pendant with the Hellenic cameo profile of the mythical Persephone, and his closed fist holds a rake-as-trident at attention, marking him out as Hades (the latter association is not precise, as the trident was more an artifact of Poseidon, but the ‘Satanized’ image of the lord of the underworld as trident-bearer was widespread enough for the artist to incorporate). The association with this myth was suggested by writer Guy Davenport in The Geography of the Imagination, as well as art critic Kelly Grovier, and it’s solid enough.

Indeed, towards the top of the weather vane over a gable-roofed house behind the couple, is a sphere we might identify with the then recently discovered farthest planet (now re-classified as a non-planet), named after the infra-world deity, Pluto. The discovery of this planet and the completion of this painting date to the same year, 1930 (the one in February, setting off a debate over what to call it, and the other in August, in the wake of this debate).

Even accepting the Greek background, opinions vary on what the painting was meant to convey.

One well-established opinion (represented by Gertrude Stein and others), sees in the painting a satirical slight against the Iowan farmer. Satire, however, can operate like a grotesque at the front of a cathedral, which scares us that we might overcome fear before entering the sacred space. Mockery, the caricature, exaggeration of a stark, ‘long-faced’ quality of a place, may divest us of pretension. But that need not be the end of it.

When an artist taps into archetypes, we may plunge those depths through his art without thereby proclaiming ‘the death of the author.’ His intention, so far as we discern it, is a starting point, even if it happens that he never spelled out, or was never fully conscious of, certain of the resonances of the symbols he chose.

In an essay, “The Italian Renaissance in American Gothic,” Luciano Cheles suggests that Grant may be “critical of Iowans’ religious dogmatism,” his painting possibly intending

To suggest that dour and straight-laced people are emotionally and intellectually dead. The funereal overtones of American Gothic have already been remarked. After seeing it at the Chicago show, a Mrs. Inez Keck wrote a letter to the editor of the Des Moines Register, published on November 30, 1930, stating that “Return from the Funeral” might have been a more suitable title. Evans has described the male figure as a “living corpse.”

It is worth highlighting, in this context, that

American Gothic was painted on the premises of a funeral home, in a studio that also acted as living quarters, which … the funeral director … provided Wood from 1924 to 1935.

But Cheles also refers to Piero della Francesca’s depiction of Jesus as a possible specific visual reference for Grant. Any references to Piero’s Jesus make figures in American Gothic not definitely corpses but corpses-in-waiting, per the renewal-of-nature theme of the myth of Persephone.

There is more to the deathliness of the painting than its human expressions, however. It may also portray a cultural death.

Guy Davenport identifies the many modern elements of the house and fashion on display in Grant’s painting, beginning with the background:

The house that gives the primary meaning of the title, American Gothic, [is] a style of architecture … a revolution in domestic building that made possible the rapid rise of American cities after the Civil War and dotted the prairies with decent, neat farmhouses. It is what was first called in derision, a balloon-frame house, so easy to build … an elegant geometric … requiring no deep foundation.

And, moving to the foreground, “technically, it is, like the clothes of the farmer and his wife, a mail-order house.”

The balloon-frame house, we are told, originated in 1833 with a certain George Washington Snow, whose invention led to “a century of mechanization that provided … all standard pieces for factories.” Davenport then refers to various imports like bamboo sunscreens and the like, perhaps suggesting an element of pastiche. Mail-order fit-for-industry technique and style, together with a few additions that happen to be fashionable and affordable, make for a detached aesthetic that tends to resist, by the specificity of its ready-made, measured-out materials, the injection of local flare, even remaining frigid in the face of that a ‘lived-in’ quality a house should acquire. It looks no more lived in than Grant’s un-grainy, grit-less landscapes.

If Puritanism and industrial uniformity contextualize the painting, the identifying features of the double portrait’s subjects counter this. A nearly-marshal lack of pretension has him brandishing a farm utensil as an infernal scepter, and she has made off with a bit of ancient, old-world art, not merely Catholic, but outright pagan.

Perhaps the American rural class is dead, its cultural forms stagnant and centralized, its denizens aging. And perhaps the story does not end there, for Persephone returns to the surface world once a year, and spring lies ahead through the memory of something far behind:

If the painting is primarily a statement about Protestant diligence on the American frontier, carrying in its style and subject a wealth of information about imported technology, psychology and aesthetic, it does not turn away from a pervasive cultural theme of Mediterranean origin.

The gods, their avatars or secret loyalists, are unhappy in their American setting, but hold the line with deep-lined somber expressions, half mocking the form they happen to inhabit, half warning that archaic powers lurk behind a too-bright, too-bare, veneer.

To the degree that Greco-Roman references are a kind of hidden foreground, contrasting with the architecture of a “mail-order house” made from “standard pieces for factories,” they are a rural rebellion against the invasion of the hinterland by pragmatic, practical, modernity. And to the degree that they own that house, the dark spherical emblem dawning above it, it becomes a crucible of the cyclical rhythm which the Persephone-Hades myth represents, stark winter before springtime, rather than a faithful manifestation of modern narratives about linear historical progress.

Alternatively, the Persephone and Hades archetypes may be the cause, rather than solution, to rural depression, representing the cycle of sowing and reaping in which farmers are enmeshed, or as emblems for unhappy relations between persons or persons with nature, given that Hades is said to have kidnapped his unwilling queen. Hades and Puritan industriousness would be allies, rather than contrasting, forces. The extremity of a certain Christianity and modernity have led to a darkly pagan and archaic state.

Either way, whether the rural countryside breaks with ingrained stagnant paradigms and fatalistic, vegetative naturalism, or finds inspiration in nature to enliven ancient forms and rebel against a deracinating (post-)modernity, we can use American Gothic to articulate a mythic frame through which to view what Dutch and other farmers are showing us, contra Marx: that they are today’s revolutionary class.