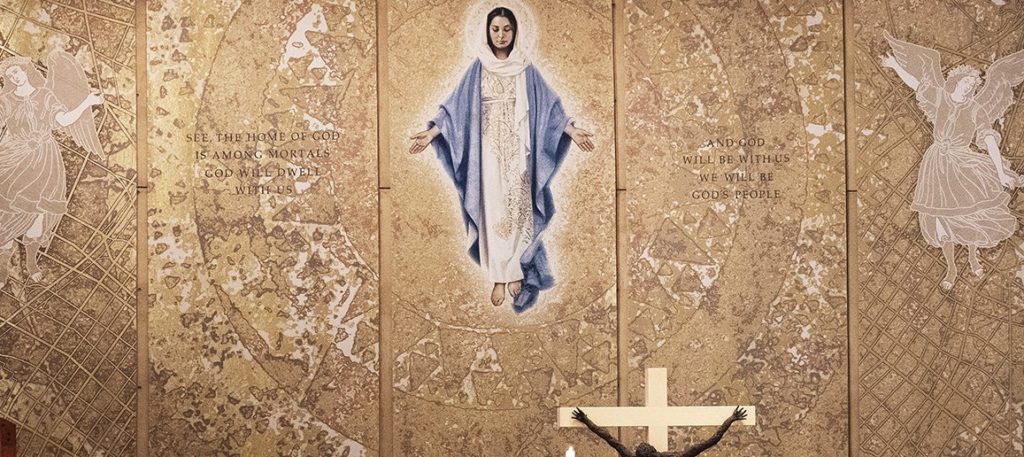

The Marian tapestry at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels unveiled on January 1, 2021.

Victor Alemán via California Catholic Daily

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Are we nomads by nature, or do we naturally look for homes wherever we go? The foxes have holes and the birds of heaven have nests, but the Son of Man does not have a place where He may lay His head (Matthew 8:20).

Even in our wanderlust, I think, we look for homes to anchor us; even when we run from home, we are looking for it.

_____________________________

The night started out great. I was 18, drinking sangria on the streets of Barcelona. I’d met up with a few American friends from back home who were four or five years older. In teenage-measured time that was significant. They had seen and done things I had only watched on TV. They were the gatekeepers to my adulthood. I would follow them and hope that they let me in.

Barcelona’s Gothic Quarter (Barrio Gótico) is a labyrinthine maze of streets. To an American, especially an inebriated one, every corner and turn starts to look the same. My older friends were dancing next to me in a nightclub, but then they were gone. They were dancing with some girls; then they just weren’t there anymore.

Then the night started to turn. Where were my friends? What was the name of my hostel? The bottom fell out of my alcoholic euphoria. I started sinking. I walked the streets looking for them. I was turned away from hotels by receptionists who told me it was too late to get a room. In a sea of party-goers, in the early hours before dawn, I was walking the streets without a destination. No place to go. Was this how the homeless felt the first time they hit the streets, before familiarity and routine took over? Were they as lonely and panicked as I was now?

The foxes have holes and the birds of heaven have nests, but the Son of Man does not have a place where He may lay His head.

At dawn, I boarded a half-empty train to a destination three and a half hours away. I watched the sunrise over the Mediterranean from my window as the glass swayed slightly with the curves and clacking of the tracks. I prayed, without knowing how or that I was doing so, that the family that had hosted me there a few years ago would answer the phone when I got there. By the mercy of God, they did. After a night of restless, frantic searching, I found a place to lay my head.

It felt odd, in the middle of a hot day in the Spanish summer, with smells of food cooking in the kitchen below, to bury my head in the pillow. I learned that sleep and a place to rest my head are not the same thing.

_____________________________

Our struggles have a way of re-confronting us, no matter how diligently we seek to avoid them; and no matter how much we claim to have grown out of them. Eight or nine years later, as a graduate student, I returned to Spain, again alone. This time it was Madrid, for dissertation research at the national library (Biblioteca Nacional). It was a cavernous, museum-like, and semi-militarized space. You had to check in your bags and flip open the pages of your notebooks, lest you try to smuggle out pages of rare manuscripts. When you looked at the manuscripts you had to wear gloves. At the basement level was a cafeteria where the scholars—and those who pretended to be, or sought to be scholars—could have coffee or lunch, eating and drinking in semi-hushed voices. The library was a secular sanctuary of sorts, where the dead lived on and continued to speak through vellum.

Even kings of the absolutist era, whose looping calligraphy I saw in the manuscripts, had aspirations, mundane or otherwise. They sought to instruct their servants in the basics of traditional court ritual; and they sought communion between the living and the dead. Philip IV believed that a Spanish mystic communicated with his young son in purgatory. One of them, Maria Jesus de Agreda, told Philip that she bilocated—remaining physically in Spain but speaking to Indians in New Mexico and Arizona who sought salvation and protection from the ruthless Apaches.

The church near my hostel was almost the size of a cathedral. It stood as if to challenge the light-hearted secularism of the passers-by. The congregants for morning Mass on weekdays were usually the ones who couldn’t simply blast past the domed landmark of defiance anyway—the elderly. Like motorists on a highway, they wanted a rest stop. To enter the church you had to pass a beggar and step over a threshold while opening a heavy wooden door that creaked loudly no matter how you pushed it.

The priest spoke from behind shaded glasses, almost as if to obscure his own face, making it seem like his words came from elsewhere. His voice echoed to the ceilings and back, accentuating the vacancy of the pews. I knelt in my pew, learning to pray, still hearing the sputtering of vespas and honk of car horns in the street. Outside I was nobody—a fledgling scholar with imposter syndrome trying to look purposeful and busy. The streets of Madrid, I knew, could swallow me just as easily as they had in Barcelona. Inside the church I was closer to home.

As I knelt praying, another door opened and closed: the confessional. A woman behind me pointed at the confessional, wondering if I was waiting. It was as if she knew. But I didn’t go in. That would come later, on the eve of my confirmation. Looking back, I now realize that there is a time and a place and a plan—God’s plan—for everything.

I sat there wondering how to be reverent and pious. A revelation came to me in the form of a fleeing comment from my father: “When I pray, l feel like God is looking right over my shoulder—like he’s touching my back.” He didn’t understand, because he never felt, the feeling that God wasn’t there. The gift of faith and its antipode, doubt.

As I prayed in the church, I wished to be elsewhere. Two places at once. To be with my wife-to-be stateside, across the Atlantic, not here and now; and to know eternal rest in God’s embrace. Eight or nine years later, I was still looking for a place to rest my head. But in the church I felt closer than I had before. The light of our Lord was falling upon me. I could feel it on my skin and in my heart and lungs that scraped against my ribcage to meet the light.

_____________________________

“Blessed the man who finds refuge in you,

in their hearts are pilgrim roads.” (Psalm 84:6)

A WASP by birth and upbringing, I could not help but see the Los Angeles Cathedral, with its postmodern exterior, in a certain way. It stood for the overindulgences of Catholicism. A more austere church would have meant more mouths fed or kids sent to school. An architecture of awe was by its very nature and architecture of excess. That it looked like some abstract futurist-Guggenheim stage piece was even more of a testament to the fact that the church had lost its way. Over the course of the early 2000s I heard murmurings that the Archdiocese had bankrupted itself paying out sex abuse claims and that the Cathedral’s interior was barren for lack of funds. That was how I’d thought of the Catholic Church in my youth—a hollow shell of its former self; a glory that, contrary to Scripture, was ending. An ostentatious exterior and a wasteland on the inside was an apt visual metaphor. Or so I thought.

As if by instinct or intuition, I didn’t even go to the Los Angeles Cathedral when I became a Catholic. Until, that is, our suburban parish priest was relocated there and we promised to visit him. When I stepped onto the escalator from the parking garage I expected something garish or tawdry.

Even though the Cathedral was not the same kind of landmark I’d crossed in Europe on my journey to the Faith (no dome, no gothic spiral towers) it felt the same on the inside. The floors had the sheen of finely polished stone—alabaster or marble perhaps. The muffled voices echoed to the ceiling. All Cathedrals, I realized, have a smell, a sound, and a feel that binds them to one another; it’s a congruity of design that unites believers wherever they go. When I knelt in the pews in Los Angeles I saw myself, and others, kneeling in the pews in Madrid and in the church where I was married in North-Central Illinois an hour from the border with Iowa, and in all the cathedrals of Europe in which I had ever set foot, however briefly. This was the feeling of a home that followed you wherever you went, and stayed with you if you stayed put. You could move, but it didn’t.

Looking at the crucifix, the Virgin Mother above it on a tapestry, and the cross-shaped window frame above both, created the sensory experience that all the atheists and agnostics—I now understood—were desperately fighting against. It was the architecture of awe that poured light into your heart. They tried to fight the wonder by explaining it away as cheap tricks—the optical illusion and pageantry designed to turn your wallet inside out and make you feel better. These were the thoughts they told themselves in order not to be overwhelmed. To not get carried away. To not be taken. They were denying their senses and denying the space inside them where reason and faith converge and find a common dwelling place. Lord, help me not to stray from the pilgrim road that unfurls in my heart.

In the ceiling above the altar, under the cedar beams themselves, is a laminated plaque, with a verse from Psalm 84: “As the sparrow finds a home and the swallow a nest to settle her young, my home is by your altars, Lord of hosts, my king and my God!”