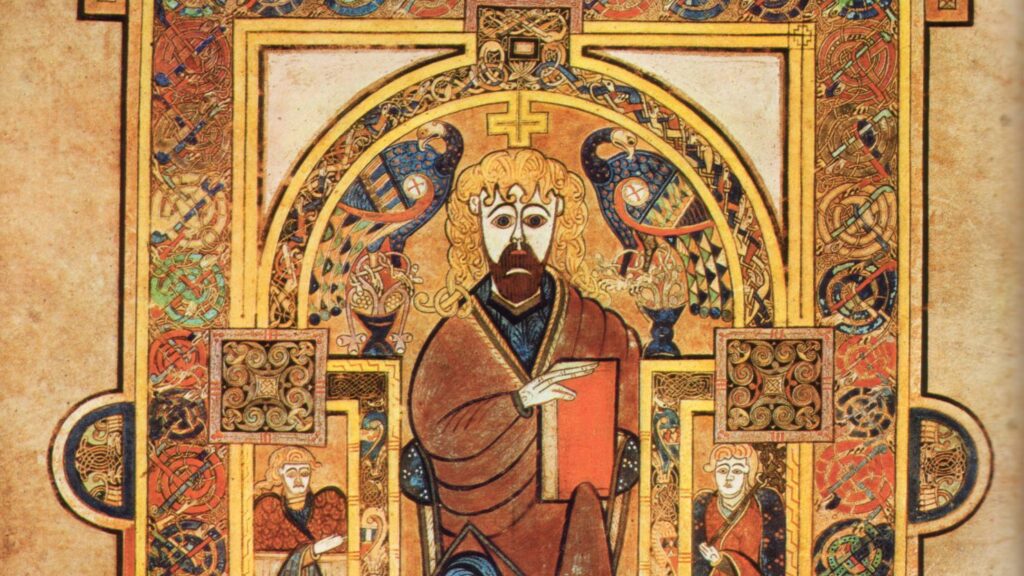

Christ Enthroned from the Book of Kells (ca. 750–early 9th century), scanned from Treasures of Irish Art, 1500 B.C. to 1500 A.D.: From the Collections of the National Museum of Ireland, Royal Irish Academy, & Trinity College, Dublin, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1977 (ISBN 0394428072)

The term ‘egregore’ belongs to Hermetic philosophy and to Western esotericism more broadly. The notion of ‘egregore’ is not dissimilar to that of ‘tulpa’ in Tibetan Buddhism, the latter being a spiritual agent generated by intense concentration of an elite monastic practitioner. ‘Egregore’ is different, however, because according to the simplest definition, it is a spiritual force that arises out of the collective commitment of a people to a falsehood.

I once thought that I was eccentric in appealing to the notion of ‘egregores’ to explain, at least in part, the chaotic world of ideological squabbles that we now inhabit. But then, a couple of years ago, I attended a dinner at a friend’s farmstead. During the meal, a discussion began concerning the future of the British Conservative Party. Everything indicated that the topic was going to be tiresome, when unexpectedly a youngish man at the other end of the table opined: “There is no hope for the Tories until they are somehow freed from the egregore that’s been controlling them since the time of Robert Peel.” I looked up from my venison cutlet in astonishment, an emotion that intensified as all those around the table nodded in agreement as if the young man had only commented upon the weather.

Many there are, it seems, who in trying to explain our civilisational collapse, are looking to the peripheries of the wider spiritual tradition of the West.

The exact metaphysical structure of egregores continues to be disputed. It remains obscure how human beings can, merely by thoughts and words, generate a spiritual being into existence and then be bound and fettered by such a spirit. The reason for this ambiguity is partly because egregores only make sense when considered within a category of knowledge and practice so readily dismissed today, namely magic. The art of magic precisely holds that special words and incantations, with gestures and the use of distinct artefacts, accompanied by extreme mental concentration, can together possess a causal power beyond what belongs to common communication.

The Western world has always believed in magic. It has always held that curses exist and that they can be placed on people, animals, plants, fungi, and inanimate objects. And the Western world has always held that such curses can be banished by special words, special objects, and special concentration, which in that order it has been content to call ‘blessings,’ ‘sacramentals,’ and ‘prayer.’ In short, even the most orthodox in the West have always believed in what the Hermeticist calls the opposing forces of ‘goetia,’ or black magic, and ‘theurgy,’ or sacred magic—though they generally would not put it in such terms.

One may retort that when a person blesses a cursed object, God and His mediating saints and angels bring about the effect, not the person who is blessing. Perhaps, but neither is the person doing the blessing accidental to the process of banishing the curse. Conversely, black magic has its effects on account of the operation of demons, but that doesn’t mean that the spell-casting warlock is accidental to the evil manifested—he clearly is a necessary part.

Hence, we can think of egregores as generated curses that arise from the kind of concentration entailed by collective commitment to falsehoods. Egregores, then, are essentially hexes which take on lives of their own and, in turn, assume control of their conjurers.

The Christian mind is inclined to understand all evil spirits as demons. Demons, however, belonging as they do to the angelic genus, transcend human beings in the ontological chain of being employed by the Church’s traditional theology. That is why demons descended—or ‘fell,’ to use the more homiletic terminology—from above to below. Egregores, on the other hand, rise from below to above, being conjured by human minds enslaved by error. In the words of the great Christian Hermeticist Valentin Tomberg, an egregore “owes his existence to collective generation from below.” But just as blessings are not angels yet do require angels to bring about their effects, so too are egregores, who are not demons but emerge in part through the action of demons and are themselves at least demonic.

This may all sound rather antiquated and maybe quite bizarre, but we all still seem nonetheless to believe in magic, or at least act as if magic were real. To observe a crowd of protestors marching through the streets, chanting some mindless slogan over and over with various gestures and performances, is to witness the collective commitment to an idea, which the people in question believe will be realised through united incantations. Often, such people cannot explain what they want and how they think they will get it. They just know, in a way mysterious to everyone, including themselves, that they are righteous and that they are being led by something. As Joseph de Maistre put it, “the people did not lead the Revolution; the Revolution led the people.” In such cases, it looks a lot like we are dealing with egregores.

Whilst believing it has outgrown such ‘delusions,’ the Western world continues to believe in both blessings and curses. Only recently, the Catholic Church’s hierarchy got itself into hot water over this very matter when its curia issued Fiducia Supplicans, its declaration permitting priests to bless ‘irregular couples,’ including same-sex couples. (The document only permits blessings of the people in those irregular unions, not of the unions themselves; but given that any couple receiving such a blessing will present themselves as a union, the document’s distinction is one without a difference, and thus a work of base sophistry.) Basically, the Church’s leadership broke under pressure from those who have rejected the Christian religion’s anthropology and moral framework, and more than that, they rejected the very notion that there is any opposition between the Church and the world—an opposition on which the very imperative to preach the Gospel is established.

Having rejected the life of nature, which the life of grace elevates and transforms, people in such unions nevertheless wanted to be blessed by the Church. The Church’s leaders, as we should have anticipated, yielded. But the question remains: what is this strange, intangible thing called a ‘blessing’ that is coveted by those who reject the worldview to which it belongs? And why is it so important that even deviants and secularists desire to receive one?

Maybe, one might suggest, the desire to receive a blessing stems from nothing more than a basic need for approval. But had the Church merely issued a memo declaring that it approved of—or at least did not condemn—homosexual unions, that would have been widely deemed insufficient. The immediate response would have been to ask, “Then why can’t we receive a blessing?” The fact is, as embarrassing as it might seem, we still believe that special words said with special concentration, perhaps combined with special gestures and special artefacts, can possess a special causal power when aided by special, powerful spirits. That is, we still believe in magic, even the most secularised among us.

Many a time, I have had the experience of speaking with someone and suddenly realising that my interlocutor is so captured by a set of ideological abstractions that he cannot conceive of an idea unless couched in the terms of his a priori commitments—during which process the idea will likely get lost in any case. The problem is similar to that of disagreeing on a first principle, which, as Aristotle observed, makes further dialogue impossible. Ultimately, I find that my converser inhabits a different epistemic universe led by different forces. In short, I find him to be under an egregore.

Recently, I visited an old friend, a monk, at his priory. He and I discussed the notion of egregores in some depth. Eventually he said, “It seems to me that what the Hermetic tradition calls ‘egregore,’ the mainstream Christian tradition would call ‘antichrist.’” Then, I thought: what, indeed, could antichrist—the antithesis of Christ—be? The spiritual Logos descended into matter, while egregores are spiritual error structures that arise from the material plain. The truth became incarnate, while egregores are falsehoods that become spirits. The Incarnation is one; egregores are many.

Perhaps, then, when we read the following words of Saint John the Divine, it is the danger of egregores that we ought to have in mind:

Many antichrists have come; therefore, we know that it is the last hour. They went out from us, but they were not of us.” (1 John 2:18-19)

What are these ‘antichrists,’ these many beings that have their source in us but are not—or are no longer—part of us? I venture to suggest that the Beloved Disciple is warning the Church about the reign of egregore.

The ‘reign of egregore’ is something to which we are now fully accustomed, whether we would use that phrase or not. In many respects, the 20th century was the great epoch of the egregores. During World War II, the egregores of fascism, communism, and liberalism—all spawn of the great egregore of 1789—took control of entire populations and drove them into violence. True, the forces of evil lost the war, but from that, it does not follow that the forces of good won the war. The egregore of liberalism emerged triumphant, and almost no one who fought in that diabolical conflict, which saw the baptised murder the baptised, really knew what he was fighting for.

In the decades immediately following that colossal war of the egregores, the nations of the West embraced the rapid atomisation of the individual, the disunion of the sexes, the erosion of the family, the dissemination of pornography, the murder of the unborn, and the celebration of homosexuality, all aided and fomented with legislative acts. Ancient cities were transformed into colourless, concrete pens. Our musical tradition was discarded in favour of a thudding, torturous background noise. Our clothes were replaced with plastic coverings made by distant child slaves. And all the while, we were told that the name of what we beheld was ‘freedom.’

The war’s veterans were condemned to look on with bewilderment as the lands for which they’d fought were remade into an earthly hell. Even now, all the curses of the egregore of liberalism can hardly be questioned—even by self-identified ‘conservatives’ (who quickly learn to celebrate them anyway)—without receiving a tirade of outrage from those under the spell of ‘progress.’

As I have suggested, a truth that has become incarnate is the antithesis of a falsehood that has grown into a spirit. The Incarnation of the Eternal Logos in Jesus Christ is the great pivotal repudiation of the reign of egregore in history. For this reason, life in Christ—‘the Way,’ as the early Christians called their religion—is the only way out. And the Incarnation is extended through innumerable creative and dynamic ways in our civilisation, a civilisation that is still running on the fumes of Christendom.

In the temporal sphere and at the level of the State, the most important among those creative and dynamic ways is monarchy. Indeed, it ought not to surprise us that World War II was largely presided over by elected autocrats, a war that never would have happened were it not for the egregore of secular nationalism, which had pitted monarch against monarch in World War I in a bid to eliminate the royal principle altogether.

Above all else, monarchy privileges the particular, the personal, and the incarnate. Monarchy teaches a people that they are not bound to pledge their allegiance to a symbol, a paper constitution, or an abstract ideological schema. They can pledge their allegiance to a family, and a member of that family who will—by sitting upon the throne, wearing the diadem, and being anointed by the hand of a bishop—embody the whole nation; and by so doing, he will pledge allegiance to them.

The whole mystery of the corporate person of the nation—which is a true person who can be blamed, honoured, and even discipled (Matthew 28:19)—is distilled into the individual person of the monarch. For a sceptred nation, the truth of the national genius is concentrated in the monarch and revered as such. Hence, at the deepest level, monarchy—especially sacral monarchy—by being a truth embodied, achieves the perpetuation of the Mystery of the Incarnation in the temporal arena. By this mystery of royal theurgy, this incarnate blessing upon a nation, monarchy always stands as a living refutation and practical safeguard against the reign of egregore. If Europe is ever to become Christendom again, it will first need to be freed from the egregores that now control it, and the royal houses will thus have to play a central role in this deliverance.