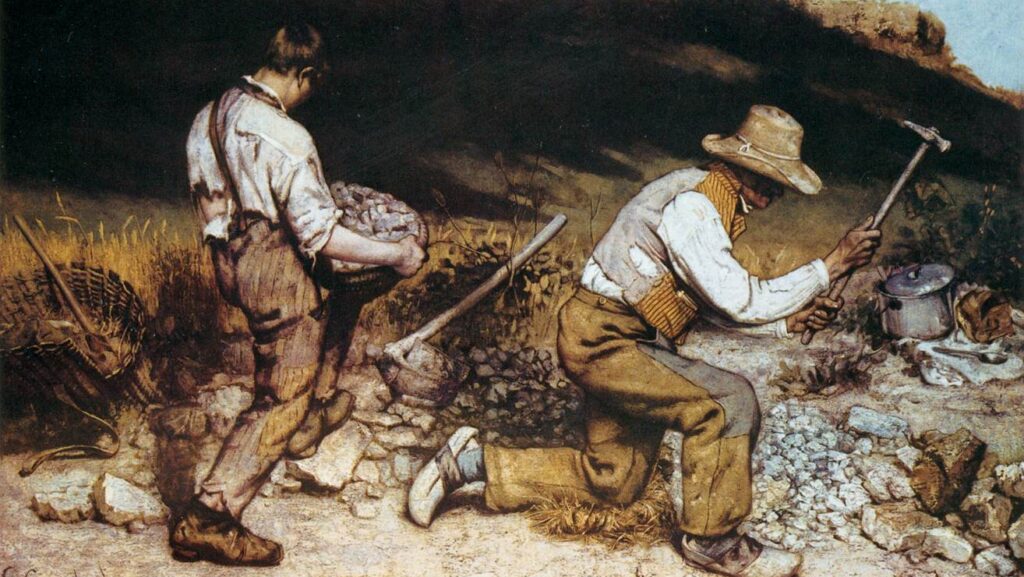

The Stone Breakers (1849), a 150 cm x 260 cm oil on canvas by Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), destroyed in the Dresden bombings

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

A couple of weeks ago, the birth of a new political party, Izquierda Española (Spanish Left), was breaking news in Spain. Every single newspaper had a piece or set of pieces about this new party and its founder, Guillermo del Valle. Most of them focused on the left-wing political bloc that this party was going to compete with, the figure of its leader, and some of the names that accompanied him in this foundational stage. There were also pieces pertaining to the ideological foundations of the party. However, very little has been said about the implications this new party may have, not only for the Spanish political Left but also for the Spanish Right.

Izquierda Española defines itself as a progressive and social-democratic party opposed to peripheral nationalisms claiming independence and hence strongly criticising their embrace by the Socialist Party (PSOE), which has consistently reached agreements with Basque and Catalan nationalist parties under the leadership of Pedro Sánchez—agreements that include a number of commitments and compromises made in order to form a government last November.

The new party is therefore explicitly anti-nationalist but very much patriotic and centralist—a position that it also holds because of its non-negotiable stance in favour of equality among Spaniards—and looks forward to going back to protecting the working class.

Another interesting fact about Izquierda Española is that it has emerged from a think tank previously founded by del Valle in 2020, El Jacobino. This think tank, as the name indicates, holds a leftist-Jacobin worldview and, therefore, also criticises the federalism that both the Socialist Party and Sumar (Podemos’ latest packaging label) have undertaken over the past few years.

It is not very common that a think tank sets up a party and not the other way around. This might be purely coincidental, and, in so doing, El Jacobino was the community-building structure that parties always emerge from. But this fact can also speak to how important ideological considerations are for this new political actor. That is also a rare phenomenon these days, where intoxicating populist rhetoric and basic rent-seeking motivations suffice to play politics and even succeed at it. However, if it is the latter case, there might be points of concern not only for the Socialist Party or Sumar but also—interestingly enough—for VOX.

The reason why the advent of Izquierda Española and its strong commitment to a belief system may pose a threat to VOX is that the right-wing party has become, over the past few years, the party of the working class in Spain. This transition has been very explicit, as part of a strategy well designed and even better implemented.

VOX’s transformation has followed the pattern of the New Right across the West. As a matter of fact, one of the main features of this New Right—which borrows its name from Alain de Benoist’s Nouvelle Droite—is its concern for the working class. There are both ideological and instrumental elements behind this; however, both are intertwined.

In the 1960s, in the midst of the Cold War, the West was rapidly recovering from the horrors and destruction of World War II and an outstanding phenomenon was taking place: the advent of the middle class. In light of this, Marxist thinkers—in particular, post-structuralists such as Foucault and Derrida—believed that the working class would soon cease to exist and hence defected from the class struggle, replacing it with new iterations of Marxist dialectics. The ‘class struggle’ was transformed into the ‘sex wars,’ and the civil rights movement—of classical liberal persuasion until then—was captured by a constellation of leftist ideologies. In short, the political Left kept busy, but it abandoned the working class, expecting its imminent demise.

However, the working class has not only survived the passing of time but has also grown. A number of elements have made them suffer the consequences of a political and economic system that benefits the few and not the many and which is increasingly hostile to national interests. This is something that has been aggravated by various consecutive crises, such as the Great Recession of 2008, the COVID-19 pandemic, etc., all of which have had the same winners and also the same losers.

This was a massive miscalculation on the Left’s part, which the New Right has taken advantage of over the past decade. This was the case of Trump with ‘the deplorables,’ as it has been the case of VOX more recently, which has articulated a number of initiatives to appeal to the working class. Perhaps the best example of this phenomenon has been the creation of Solidaridad in 2020, a trade or workers’ union that has rapidly grown, competing with ‘historic’ left-wing trade unions such as Unión General de Trabajadores y Trabajadoras (UGT), Comisiones Obreras (CCOO), of communist origins, and Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), of anarcho-syndicalist ideology.

VOX has greatly benefited from this transition electorally, but this transformation has also brought about a number of challenges. One has been the needed—or perhaps just sought—replacement of a considerable part of the party’s leadership, removing most of the classical liberal or liberal conservative remnants and embracing its more Lepénist-nativist side. And another has been to engage—maybe unnoticeably—with the very thing a party like VOX was meant to fight: Marxist dialectics.

It is indeed complicated to play the populist game and use the ‘people vs. elite’ rhetoric and not buy some of the class struggle discourse, just as it is hard to raise the national flag and not fall into some of the nativist claims. Here, again, Solidaridad is a very good example. A month ago, Rodrigo Alonso, MP and secretary general of Solidaridad, said publicly that “the company belongs to its workers.” This type of statement, which was subject to massive online discussions, is similar to other things he has previously said, such as to discount “the rich, as they are rich by nature.”

These types of considerations have been branded by some as straight fascism—or the Spanish flavour of it, Falangism—as an example of how the Right can also be rooted in socialism. Whatever the case may be, it is obvious that, although this type of discourse has worked in the recent past, VOX would do well to resist this temptation in the future, if not for ideological reasons, then for instrumental ones. The main reason is that, when selling a product to your customers, they will always prefer the original brand. And that is not the new Right, but the ‘good old’ Left.

In this regard, Izquierda Española—which will run in the EU elections in May—can become a headache for VOX. This is because of ideological considerations of a shared constitutional design, such as the Jacobin centralisation and homogenisation proposed by both parties, and a set of policy recommendations that emanate from the working class vision, such as the sacralisation of a safety net in the Spanish welfare state, subsidies, and social protection mechanisms.

VOX should review its ideological foundations, which might have been blurred in the fog of political war and because of its unavoidable reactive—and not proactive—mode. By doing so, it would be in a better position to resist the potential threat of Izquierda Española.

May this also be a warning for New Right political movements across Europe and the U.S. At this point, it is clear for all, Right and Left, that the working class still exists and amounts to a considerable portion of the electorate. Precisely the portion that wins elections.