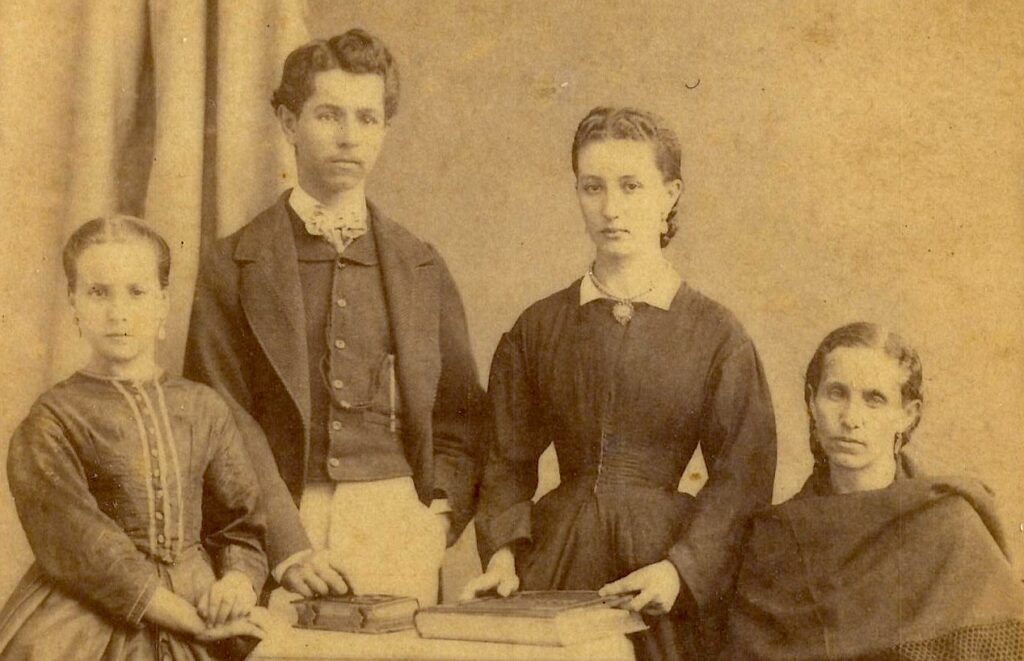

(L to R) Teresa, Rafael, Concha Lema Berrío, and Dolores Berrío (1867).

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Medellín, Colombia, is known for Pablo Escobar and his Cartel, graffiti, and the increasing number of American expats rising prices throughout the city. I was born here in 1999, I became the 14th generation born not just in the same country or region, but the same village-turned-city. As such, I inherited its story.

One of the perks of being the localest of locals is that, if you pay attention, family history is almost everywhere. I happened to find it, thanks to the pandemic, in an old hand-written Jesuit journal and a couple of letters, guarded thousands of miles away from Medellín, in the Sanctuary of Loyola’s historical archive in Spain. With them, I also found a story of grace, love of God, and generosity that family lore had already forgotten.

It is part of the Jesuit identity to be both hated and revered by the times. Such was the case in Colombia which, though Catholic, had mixed feelings about that order during the colonial times, and after. Medellín was not directly involved in the polemic—the city had never had a male religious order until the early 19th century, and a single Carmelite convent where widows spent their last years in prayer was its source of spiritual renewal.

But the Jesuits had made a name for themselves, and after the anticlerical government had expelled them from the newly independent nation, they were invited back by a new President, Mariano Ospina. It is this story, the story of the shortly-lived Jesuit outpost in Colombia in the 1840s, that was handwritten by the very Jesuits who arrived here, and which I discovered in the Basque online archives during the COVID lockdown.

President Ospina was married and had lived for a considerable time in a small village in the outskirts of Medellín, Santa Rosa de Osos, where, forty years previously, a child was born. Spanish-speaking families have two surnames: that of the father, and the mother’s maiden name: García Márquez, Ocasio Cortez, Jiménez Lema. But when this baby was born in 1801, he had only one name: Berrío—his mother’s. Colombia was still Spain’s Viceroyalty of New Grenada and a child born out of wedlock was not destined for greatness. Or so it was thought.

The grace of God would have it, as it often does, otherwise. Through unknown means, Juan José Berrío was recognized by his biological father, and became Juan José Mora y Berrío, as he would sign until his death. He married a distant cousin—a member of the upper class in Medellín—and became one of the most renowned businessmen in the growing city.

Thus, when his close acquaintance, President Ospina, had the Jesuits come back to Bogotá, the country’s capital city, Mora y Berrío did everything he could to get a handful of the new priests for Medellín. In the Jesuit narration, he is described as “one of the most pious inhabitants of his province.” Not only did he write and insist, but he collected the necessary resources for the priests to travel. Despite the opposition of some in the capital, the Father Superior sent three priests to evangelize what is now the second largest city in the country. Their names deserve to be remembered: Fathers Freyre, Laynez, and Amorós.

The priests arrived in Medellín at noon, on 29 November, 1844. What arose cannot be described as anything other than a true spiritual revival. Yes, the Jesuits faced opposition: they were stoned in a nearby town on their way to the city; prohibited from teaching in Medellín’s most prestigious high school, and libeled in defamatory pamphlets that were swiftly distributed by the anticlericals.

But despite the strong opposition, and perhaps, even, because of it, the city’s soul began to grow. While inhabitants of Rionegro, a strongly anticlerical town, had stoned them, Santa Fe and Santa Rosa de Osos received them gladly and took their teachings to heart. Conversions took place, hearts were changed, and the people rejoiced. The bishop, known to be close to the anticlerical party, surprised everyone by supporting the order’s mission. A group of women founded a confraternity in honor of Our Lady, which was spiritually led by the Jesuits. Prayer retreats became frequent, the people more devout, and even more Jesuits were sent from Bogotá.

There was still one deep desire, part of the Jesuit vocation, that was not met: teaching. Barred from the Colegio Académico, many still yearned for the priests to teach their sons. Mora y Berrío, happy as he was with the order’s presence in the city, took matters into his own hands once again. He bought a house big enough for the priests to both live in and have some classrooms, and with the help of some of his friends, he donated it to the Society of Jesus in 1845, on 19 March, the feast of Saint Joseph. The school took that very name: San José.

A few years passed and, when all seemed well, one of Mora y Berrío’s fears became real: a new government was imposed and the order was expelled from the country once again. The Jesuits would come back, enduringly next time, and found a new school, San Ignacio, that remains one of the most influential in the city’s history. But for the time being, the priests were exiled to Kingston.

In the same archive where the Jesuit diary is found, there are over fifteen letters from different people, men and women of Medellín, who, through their writings to the exiled Fr. Freyre show how much the Jesuit presence revitalized the city and changed it indelibly. There are two such letters that are dear to my heart. One, that doesn’t say much, is signed by over forty women, the members of the Marian confraternity. Among them are two of my direct ancestors. Women who loved, and loved dearly, the exiled priests who had so changed their lives. This letter is also an unknown yet tremendously valuable piece of history: the handwritten signatures of the most important women in Medellín, in a time in which we have almost nothing written by women in the country.

The second letter was sent by Mora y Berrío himself, and narrates the death of Enrique, one of his sons, in detail. As he was an important businessman, other archives in Colombia hold some of his letters too, but this one is different. He poured out his heart to his spiritual father and revealed the depths of his soul in the midst of tragedy. On display is his love for the Lord, the Church, and the sacraments, his docility to God’s plan, his devotion to his wife and children, and his spiritual fidelity. After describing Enrique’s passing, he concludes with a Job-like cry: “for everything, may God be blessed and adored.”

When Juan José Mora y Berrío passed away, in 1887, he left plenty of children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren, as well as a considerable inheritance. The probate trial that followed was long and difficult. I like to believe that, with his material bequest he also left a spiritual one.

His daughter, Dolores Lema, was the first harpist the growing city ever had—and, even as a young widow with three children, donated all the income from her concerts to charity. Her children were raised in her father’s (Mora y Berrío) house. One of them, Rafael Lema, was my mother’s great-grandfather. This is Mora y Berrío’s legacy. This is his story. And in a sense is also my story. This is a story of God’s mercy shown to a family: my own family. A story we didn’t even remember.

In one of the few books about Jesuit history in Colombia, there’s a short biography of each of the four gentlemen who donated the building that became San José, the school. Each bio begins with an account of their impressive accomplishments: they were independence war veterans, politicians, successful businessmen, and so forth… But there’s one, and one only, that starts rather differently: “Juan José Mora y Berrío: pious and fervent Christian, animated by an unbreakable faith…”

I own a picture of Mr. Mora-Berrío, my great-great-great-great grandfather, and, inadvertently, my namesake. It reminds me that, with God’s grace, we will be remembered first and foremost—here or hereafter—not for our successes or our accomplishments, but for our love.

In Memoriam—Dr. Rodrigo Lema-Calle, the author’s grandfather.