Christians everywhere are preparing for the greatest event of their calendar, namely Easter, the celebration of Jesus Christ’s resurrection and his conquest over sin and death. Before this great feast, however, the baptised will gather in their churches on Good Friday to kneel before the cross and kiss it in thanksgiving for their redemption. Good Friday, that day when Jesus Christ died on Calvary, was the day when everything changed. The God-man, who was perfectly innocent, prayed for his murderers as they nailed him to the cross.

By this great sacrifice, the order of grace was established, by which humankind could be transformed in the only way that makes life beautiful. Thereafter, this sacrifice has had to be repeated, in some way or other, in the lives of all the baptised. I have learned more about this mystery from the story of a little girl, who died at the beginning of the last century, than perhaps from anyone else besides the Master Himself.

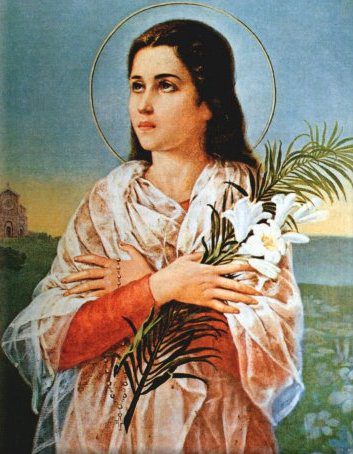

Born in 1890, Maria Goretti was the third of seven children in a family struck by almost unimaginable poverty. By the time she was five, the Goretti family had been compelled to give up their small unproductive farmstead and were put to work as labourers for other farmers. Soon after moving to the west coast of Italy in pursuit of employment, Maria’s father died from malaria when she was only nine years old. Henceforth, her mother, Assunta, and siblings went out into the fields to work each day, while Maria’s job was to stay back to cook, clean, and look after baby Teresa, her youngest sibling. The fatherless family shared lodgings with other farm labourers in an uncomfortable dwelling. Maria would often try to make herself useful to the other working families, cooking for them and mending their clothes.

One young labourer, the twenty-year-old Alessandro Serenelli, driven by perverted appetite, made increasingly aggressive advances at the eleven-year-old Maria whenever he found her alone looking after little Teresa. Maria, fearing for Alessandro’s soul, prayed for him daily. On Sundays, she would walk for hours with her family to attend Holy Mass, often in great pain due to poor footwear; she offered to God many of her sufferings, it is believed, for Alessandro’s salvation.

One day, when the Goretti family were working in the fields, and Maria was alone tending to her baby sister, Alessandro appeared with a knife. Pointing the blade at Maria, he told her to undress, that he might satisfy his craving. She protested, telling him that she could not bear the thought of him going to hell. He ripped her clothes, shouting and grabbing in frenzied frustration. “No, Alessandro, no!” she cried out, “God does not want this for you!” He held her by the neck and began to strangle her, but she freed herself from his grip. Finally, he plunged the knife into that little girl at whose feet he should have fallen prostrate in veneration. Again and again, he thrust the knife into her struggling figure. As Alessandro rent from that body Italy’s purest soul, in her fading voice prayers were offered to God for his redemption. Fourteen times Alessandro sent the blade back to the inner chamber of Maria’s sacred body before he fled that wretched house which, by his malevolence, had been sanctified with the blood of a saint. Maria escaped the indignity of rape only by giving up her life.

Hearing the cries of baby Teresa, Maria’s mother, Assunta, returned to the house to find Maria perishing upon the floor. Maria was rushed to the nearest hospital. For twenty-four hours the doctors tried keep her alive, but on July 6th, 1902, Maria breathed her last breath. Before she died, with her remaining energy, she told her mother and the chief of police what had happened the day before, and of two previous attempts by Alessandro to rape her (about which she had been afraid to talk, as he had threatened to kill her if she said a word of it to anyone). Hearing this, Assunta asked Maria if she was able forgive Alessandro. “I forgive him,” Maria replied, “I forgive him, and I want him with me in heaven forever.” These were her last words.

Alessandro was to be sentenced to death, but due to Assunta’s intercession, he was given 30 years’ imprisonment. For three years, Alessandro remained unrepentant. Priests and even a bishop visited him, hoping of encouraging him to repent and confess his sins. He would scream and try to attack anyone who came to visit him.

Then, one night, Alessandro awoke to see Maria standing in his prison cell, at the end of his bed, looking kindly at him. It is not known what Maria, in this extraordinary vision, said to Alessandro, but years later he wrote:

Maria… was my good angel, sent to me by Providence to guide and save me. I still have impressed upon my heart her words of rebuke and of pardon. She prayed for me. She interceded for her murderer.

Having served his three decades in prison, Alessandro went to visit Assunta Goretti. On seeing the mother of his victim, he collapsed at her feet and begged for forgiveness, at which she explained that she had forgiven him long ago. The following day, Assunta and Alessandro went to Holy Mass together; they sat side-by-side before the eternal sacrifice to which Maria had so perfectly united herself. Soon after this meeting, Alessandro sought out a life of reparation, joining as a lay brother what was then one of the strictest religious orders, the Capuchin Franciscans, where he remained in penance for the rest of his life.

On the 24th of June, 1950, Assunta attended the canonisation of her daughter. For the first time in its history, St. Peter’s Basilica could not be used as it was too small to hold all those in attendance. Therefore, the event was moved to St. Peter’s Square, marking the first ever open-air canonisation. A little girl, who lived in extreme poverty and died in obscurity, burst the walls of the world’s largest church.

About a decade ago, I visited the house where the Goretti family had lived. I knelt down in the exact place where Maria was attacked, and I asked her—as the Book of Ezekiel puts it—to take from me my heart of stone and replace it with a heart of flesh. I have dedicated much of my life to studying the great philosophers and scholars of our civilisation, but from none have I learned as much about true human flourishing as I have from the peasant girl of Nettuno.

In ancient times, human flourishing was seen to be conditional on the accumulation of worldly privileges, the overcoming of ignorance, and the cultivation of virtuous habits. In turn, if you were not—by mere accident—wealthy, educated, and a person of leisure, it was inconceivable that you could enjoy a life of human flourishing. In the teaching of Jesus Christ, however, wretchedness is primarily presented as an interior state, and not one that can be overcome simply by learning—as Socrates, for example, had thought. Rather, for Jesus Christ, human flourishing is something that hinges on what kind of ‘heart’ one has. The great philosopher Robert Spaemann explains:

It is not the lottery of nature, a function of the genes and education, that determined whether or not the absolute claim of the rational good prevails in any human life; the basis lies in the human being him- or herself. Following the New Testament, Christianity calls this basis “the heart”. Unlike reason, which is by definition always rational, but is sometimes unenlightened and ineffective in exerting control, the heart is always in control, but makes its own decision as to who or what it will accept direction from. On what basis does it make that decision? On the basis that it is a heart of such and such a kind, with such and such a “nature,” about which it can do nothing? No. According to this account the heart is not a nature. There is no condition of the heart, no specific quality, that could be a basis for defection from good or for love of darkness. The heart is its own basis, and needs no further basis.

As Spaemann points out above, in the order established by Christianity, the truly flourishing human life—the life which lays claim to ‘the rational good’ in an absolute way—is not available only to those in a societally rare and privileged position. Rather, enjoying a truly flourishing human existence is available to all, depending only on what kind of heart one possesses. Put another way, human flourishing is not something you accomplish, but something that happens to you, as God enters the depths of your heart and transforms you by His grace. Such transformation by grace is something that can be enjoyed by a peasant as much as by an emperor, as the communion of saints reveals.

Neither Plato nor Aristotle would have considered Maria Goretti an example of human flourishing. She was a social outcast, poor, uneducated, and with almost no sphere of influence of her own, who, after a short life of constant suffering and struggle, was brutally murdered. For the ancient Greek thinkers, she would have been an example of the antithesis of a flourishing existence.

Jesus Christ, however, taught that true flourishing was not brought about by ‘adding onto nature’ knowledge and good habits of conduct, but by the transformation of what is most fundamental in the individual: the kind of individual one is unfolds ‘out of the heart’ (Matthew 15:19). Maria Goretti, according to the Christian account of human flourishing, was a supreme teacher. Her heart overflowed with love for everyone, even for the man who sought to take everything from her. She had achieved the state of true human flourishing for she had been transformed in divine love, and it is in the mystery of such transformation that we find the unique character of our civilisation. Our civilisation is special, because ours is a civilisation in which a pitiable peasant girl, labouring away in obscurity, can transfigure the world by silently walking life’s pilgrimage as a living icon of the Saviour.

The heart is presented by Christianity as that which is most fundamental in human existence, the foundation and basis beyond which one can look no further for an account of what one is. The heart tells us what one is—not as a mere instance of our species—but as an irreplaceable and non-transferable individual. As Spaemann puts it: “the heart is not a nature.” For Spaemann, then, if one really seeks to understand what the human person is, one must look to the Christian concept of “the heart” as “the source of the discovery of the person.”

Occasionally, the world is gifted an example of the full actualisation of human personhood in a concrete, existential, living out of heavenly light that radiates forth and continues to shine through the ages. Such a gift reveals the dynamic, self-giving, eruption of divine love in a human being who has become a real person through a transformative relationship with Jesus Christ. Thus, if one wants to know what the human person is, a hollow shell of which is only observable independently of the grace with which Jesus’ sacrifice has flooded the world, then look no further than St. Maria Goretti. All the darkness of Good Friday, in which the sin of man is revealed in Jesus’ wounds, and all the light of Easter Sunday, in which the redemption of man shines out from the empty tomb, is amplified by the participation of the saints in this great work of redemption. In the life, death, forgiveness, and intercession of little Maria, who made Jesus’ prayer for his murderers her own, we are shown all that we must hope to become if we hope to flourish.