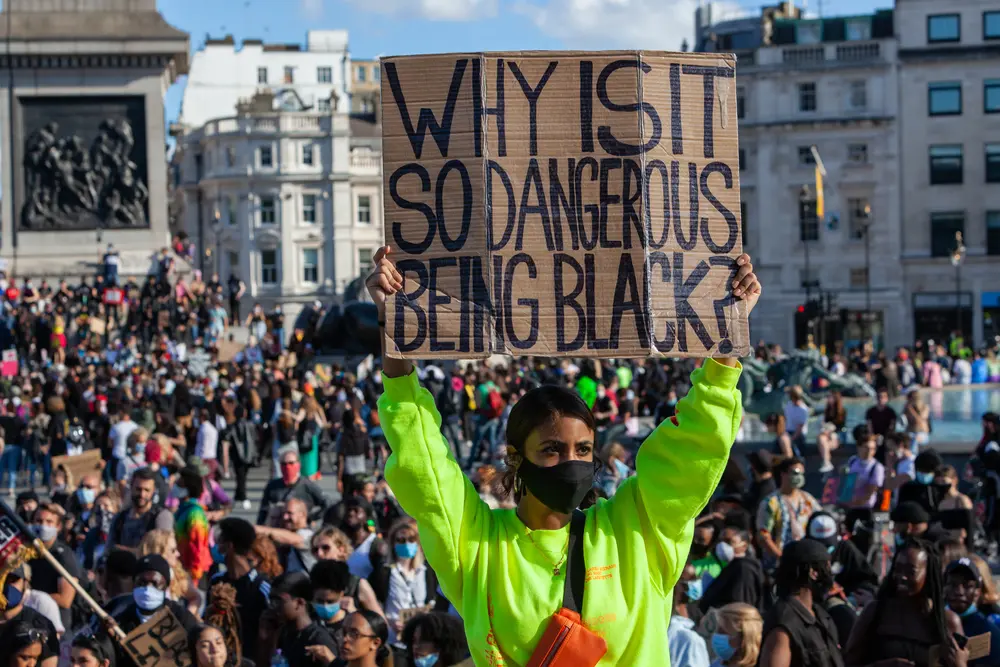

Black Lives Matter protest, London, England

When the ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ campaign broke out in Oxford, Nigel Biggar rose to the occasion and engaged the ‘decolonising’ agitators in a public debate. He now admits to having been a little more naïve back in 2015 than he is today. For one thing, he seemed to think that this was a good faith discussion about history. Yet the leader of the Rhodes Must Fall side made it clear within the first minute of his speech that the Cecil Rhodes statue outside Oriel College, Oxford, is not a stand-alone offence, but just one “emblem” among many of an inexpungeable guilt, a totemic symbol of a civilisation that was built on white supremacy. Europe, he added, is still plagued by the legacy of this original sin, to the ‘systemic’ disadvantage of non-Europeans who for some reason continue to cross the Mediterranean in vast numbers to reach this irredeemably racist hellhole.

This must have caught Biggar off-guard, for he showed up to the debate armed with more old-fashioned weapons—things like facts, figures, even quotes from Rhodes himself, none of which his opponents bothered to rebut. “Thus did I stumble, blindly, into the Imperial History Wars,” he recalls in his splendid book, Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning. Biggar won the debate by Socratic standards, but not by the sophistical ones operative on the other side and, regrettably it seems, in the packed Oxford Union audience as well. This begs the question: what really motivated this enthusiastic crowd, and what motivates others like them, if not a noble hunger for the vicarious experience and practical wisdom that knowledge of history confers?

It would seem that the sins of our ancestors, often exaggerated and at times invented out of whole cloth, are not the justification for a new blood libel against Europeans; they are the pretext for it, since they give the appearance of legitimacy to otherwise appalling claims against the freedom, prosperity, and culture of European peoples.

When I was in sixth form, Andrea Levy’s distinctly average novel, Small Island, was required reading, and the notion that the British Empire was a predatory, rapacious project, spearheaded by evil racists, was required thinking when it came to analysing this story about Jamaican immigrants navigating hostility in post-war England. For me, it was a choice between playing the game or receiving a lower grade. Here is a brief excerpt from a college essay I wrote which won top marks yet still makes me cringe to this day:

Bernard [the novel’s token white villain] is unable to reconcile his glorious, racially pure notion of Britain with the reality that its capital is in ruins and colonised peoples from the West Indies—not returning English soldiers—are required to rebuild it.

A rigorous, fair-minded marking scheme would have torn this sentence to shreds. First, the Nazi lust for racial purity has never been the order of the day in England. But second, the novel is set in 1948. And the demographics of London, even as late as 1961, remained all but entirely homogeneous: 97.7% white British. To suggest that immigrants from the colonies were “required” to rebuild the city, while the millions of returning English soldiers lounged around on their backsides, was factually preposterous and a grave insult to my ancestors. I should have been awarded an F.

Yet this lie has now spread beyond the curriculum to infect and hegemonise mainstream political discourse in Britain. Both Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and the Labour mayor of London Sadiq Khan never tire of taunting us with the myth that our country would be nothing without immigration, that “diversity built Britain.” Why is so much propaganda churned out to convince us of something so demonstrably untrue? A desire on the part of tribalistic, self-appointed ‘leaders’ of minority groups to delegitimize the British people’s right to a national home clearly plays a part. The recent adverts on the London underground certainly suggest as much. Anyone travelling through the capital today cannot escape the manipulation. Plastered on the walls are wretched poems celebrating Britain’s “colonisation in reverse,” raising the question of whether immigration is a benefit, as progressives like to tell us, or a kind of revenge for the ‘sin’ of empire, as they cannot help implying in unwise moments of candour. There is another poem, again signed off by the mayor of London and the taxpayer-funded British Arts Council, which reads:

But your home was built

On our blood

On our sacrifice

On our two-toned

tongue

So yes

We do belong

More than.

Apart from the unforgivably tin-eared rhyming of “tongue” with “belong,” what is this if not an attempt to browbeat the founding, long-established, reasonably homogeneous, ancestral population of Britain into relinquishing their right to a home? This is not a cry for universal justice, but an insidious ethnic slander against one of the most tolerant host populations in the world. Combatting this narrative will require a fuller understanding of what truly motivates our opponents. To them, history is not a source of curiosity or a cause for sober reflection; it is a political tool.

The race-baiting activists also want to have it both ways. They will claim that the story of Britain is nothing but a litany of racist horrors, yet they will also argue that black people have been the leading characters of this story from the very beginning. Which is it? In a Horrible Histories sing-song that recently went viral, the BBC spent taxpayers’ money bombarding the nation’s children with a great lie about the genetic history of their homeland: “before these isles were British,” goes the chorus, “black people played their part.” We are expected to buy the idea that there has been a continuous black presence in these islands, beginning in prehistoric times and culminating in our own day with the apparent importance of public figures like Stormzy and Marcus Rashford. The only problem is that more or less every example given in the song as proof of a hidden black history is false, as the historian Tom Rowsell has explained in a thoroughly informative, entertaining video.

Debunking the BBC Horrible History of an alleged Black Britain pic.twitter.com/TvtCBDrcn5

— Tom Rowsell (@Tom_Rowsell) September 15, 2023

The overwhelming majority of black people living in Britain today are only here because they have ancestors of African descent who arrived in the last half century. When I was born in 1998, the country was still 90% white British. In fact, the genetic make-up of the British Isles has changed more since 1948 than it did in the previous 6,000 years. A geneticist would be hard-pressed finding black Britons who can trace their family history back to anyone of African descent living in England at the time of John Blanke, a black trumpeter in the court of King Henry VIII who has now been given a consecrated place on the national history curriculum. My very intelligent youngest brother, still aged 14, once had a whole lesson devoted to John Blanke; when I asked if he knew anything about Martin Luther, Thomas Cromwell, or John Calvin, he had not heard of the last two and could only give the following account of Luther’s significance: “Didn’t he start his own religion?” The socially transformative demands of racial politics alone explain this distortion of the past, such that even our best and brightest are being forged—without success in the case of my own brother, I am pleased to report—into race-obsessed know-nothings. After all, how many white Tudor players of brass instruments have their own Wikipedia page, let alone one as long as Blanke’s?

A population carefully programmed to be amnesiacs in relation to their own history will be defenceless against further attempts to demolish the cultural character of their country through mass immigration. Whatever the BBC might say, the shifting demographics of Britain are not part and parcel of a long-running historical trend, but the result of an unprecedented social experiment undertaken not only without but in clear defiance of popular consent.

Of course, we should also reassure people less caught up in the minutiae of the ‘Imperial History Wars’ that their love of country is justified and that they are right to feel hurt at seeing its most iconic figures, from Gladstone to Churchill, unfairly dragged through the mud. Nigel Biggar and countless others, especially the distinguished scholars at the History Reclaimed project, have done a vital public service in this respect. A country taught to be ashamed of its roots will lack the self-belief to bind its own people in a shared intergenerational endeavour. But we must also alert others and remain alert ourselves to the fact that a disconcertingly large number of our opponents are not humble seekers after truth who can be engaged in a Socratic dialogue, but sophists with a vendetta against European countries and intent on spreading a foul blood libel against their ancestral populations.

When the argument takes place on the Left’s self-serving terms, we are forced into a defensive posture that at best makes us seem pedantic and at worst signals our weakness. We must isolate and expose the power interests which advance behind the Left’s dubious truth claims, rather than fixate exclusively on the technical errors in these claims themselves. After all, such errors are far from accidental; they are essential to a cynical power grab which regards truth as more of a brute weapon than a spiritual calling.

Let us not be seduced by the libido dominandi ourselves. But failing to recognize it in others will immobilise us, conferring a false sense of security that we are in the midst of a lively Socratic dialogue, rather than a war for the life of our civilisation in which the sophistry of race-based activism and its malevolent motives must be exposed for all to see.