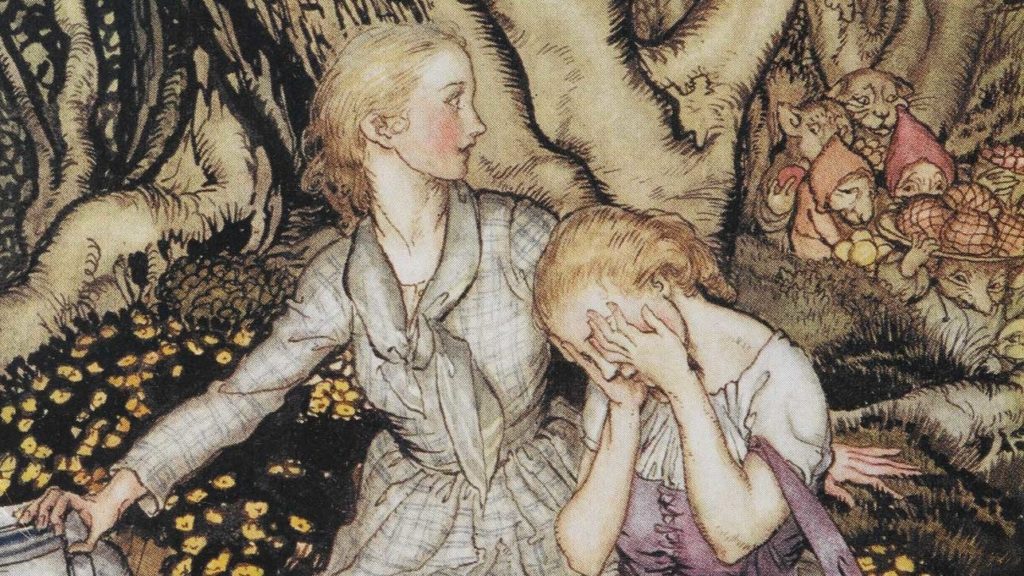

Arthur Rackham’s 1933 illustration of Christina Rosetti’s Goblin Market and other Poems.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

The internet has long been described as the chthonic domain of disincarnate troll personae, who take leave of their human hosts through gates of anonymity and, at the speed of fingers fidgeting on a keyboard, fashion themselves a body of language, of interrogatives concerning the virtue of their interlocutor’s mother and meticulously curated memes, like inspired hieroglyphs laying bear with devastating aplomb the utter vacuity of their fellow forum-dwellers’ personalities.

Through these screeds, we sometimes glean rhapsodic verses of what might be the 21st century’s own beat poetry for, indeed, there is an art to trolling. The press attributes it to sexual frustration, but social alienation is at least as strong a contributor, and more than these, the simple, perennial fact that mirth can come of mockery.

With pickaxes of mockery, teenagers will mine for mirth in the internet’s labyrinthine architecture of fora, but few will dare deploy that irony and edge-humour in the real world.

Beyond URLs,

In realms of IRL,

We see not trolls

But goblins swell.

The term ‘goblin mode’ has recently entered internet-parlance, describing an apparently quarantine-inspired attitude of slovenliness and near-abject embrace of circadian-pattern irregularity, novelty-addicted internet scrolling, and abnegation of hygiene, countering Instagram-curated photography with a defeated, devil-may-care nihilism. Vanity, the succubi and incubi of cyberspace, contend here with Lethargy, the goblin.

I am not really discussing the shamanic, theatrical acting-out of the archetype, whose eccentricity is more akin to a child’s game. Rather, we are discussing the hibernating, hole-dwelling, ‘horizontal,’ comfort and covetousness. This kind of goblin is almost the opposite of the dwarf’s industriousness, nor does it possess the aggressive verve of an orc. Its malevolence, such as it is, remains latent.

Like any species of individualistic gratification, it will tend to be magnetised by some outer force, attracted by gravity. Atoms refusing to be part of molecules, refusing to be part of cells, refusing to be part of organs, refusing to be part of persons, are alone and easily preyed upon, until they clump together into mere mass.

Soon, the conniving creature seeking its own comfort and gain may become (even if only because it lacks the ability to resist) snivelling, slavish. This is true not only in terms of participation in macro, societal structures. It is also true of personhood itself. Certain elements of the psyche will become ‘ingrown’ and weaken the subject if they refuse to be part of a grander personality by becoming subordinated to nobler elements.

We may gain further insight into the goblin spirit possessing lockdown-habituated comfort-seekers by way of Christina Rossetti’s poem The Goblin Market.

Second edition of Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market and other Poems with Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s frontispiece and title page designs, 1865.

Here, two sisters, Lizzie and Laura, are beckoned by animal-like, chimeric goblin men selling exotic fruits. As the poem’s title suggests, the first feature of goblinhood is full-spectrum mercantilism, to the point, as we will see, of commodifying the human body.

One of the two sisters, Laura, decides to answer the fiendish call. She cannot pay for the fruit in cash however, as she has none, but the men happily accept a lock of her blonde hair. A physical attribute is now compared to a commodity (“You have much gold upon your head … Buy from us with a golden curl.”) This causes her to shed a precious tear, “more rare than pearl.” Indeed, we know from folklore that goblins like shiny things. They are visual creatures and, to them, value is in appearance. Laura’s tear is part of her payment, while also signalling that she is aware and mournful of the fact that she is selling herself.

The quarantine, the precariousness of the job market, rising utility prices, the erosion of social mores, and the ease with which one’s image can be shared in an age of instantaneous virtual reproduction, have all led to the rise of platforms like OnlyFans, on which the goblinized may consume one another other.

For Laura, the fruit itself is immediately addictive, causing her to consume it compulsively and lose track of time, just as addictive fruit (amenities like food delivery, but mostly entertainment media like Netflix shows, YouTube videos, pornography, etc.) is the whole draw of modern, goblinic hermitage. The Goblin encourages compulsive consumption. Goblins inspire gobbling (as in ‘gobbling up’).

Specifically, the fruit, or Laura’s consumption of it, is described in quite clearly sexual terms, which strengthens the parallel with our cultural moment, in which eroticism is used to advertise everything, providing the primary aesthetic language of the market.

Indeed, the fact that Laura is going down a dangerous road on account of sexual transgression is made explicit with the recollection of a cautionary event involving an acquaintance of the sisters:

She thought of Jeanie in her grave,

Who should have been a bride;

But who for joys brides hope to have

Fell sick and died.

Laura, for her part, has begun her fall, which is internal, psychological. She describes the feast she received in terms alike those of the goblins themselves. The fruit, she says, was “Piled on a dish of gold, Too huge for me to hold.” Writes one, very insightful, critic (to whom my analysis is indebted on a few points): “The descriptive language employs the same pleasing aural qualities we hear in the goblins’ own descriptions of the fruits they ply. Laura has essentially adopted the language of the market.”

Just as the market may become tired of a product, or in this case, a person, indulging in a vice eventually becomes more chore than pleasure, as we become desensitised to it. Laura, therefore, stops hearing the goblin call, which Lizzie, who did not heed it, does. This causes Laura some distress, as she can no longer enjoy the fruit. The goblins, it seems, having used her, have moved on to pursuing her sister. Laura will try to plant a seed she took from one of those terrible fruits, but it does not grow. Like Monsanto’s genetically-modified seeds, these are sterile. The Goblinical economy is unproductive and tends to centralise its platforms, to consolidate its offer.

Corresponding to this bareness, Laura begins ageing prematurely, and enters what is recognizable as the modern ‘goblin mode,’ with its lethargy and incapacity for edifying labour:

She no more swept the house,

Tended the fowls or cows,

Fetch’d honey, kneaded cakes of wheat,

Brought water from the brook:

But sat down listless in the chimney-nook

And would not eat.

Now Lizzie is spurred into action. Her sister was heedless, but the solution to the consequences of this heedlessness is not to remain at home. Indeed, heedlessness has led Laura into near paralytic hermitage. To redeem Laura, Lizzie will have to venture out and face the goblins herself. The paradigm is a Christian one.

When she finds them, the goblins do not want to give Lizzie fruit in return for silver coins, because their aim is to commodify the person. They want to bring her into the exchange, as they did her sister. It is in the moment of symbolic prostitution that fruit would cease to be fruit and would become imbued with the goblins’ libido dominandi, lust to dominate. Prior to this, a legitimate exchange would have been possible. When Lizzie refuses their snares, they insult her by imputing a lack of virtue: “One called her proud, Cross-grained, uncivil.” They invoke social propriety against her, just as they refuse her money.

A certain kind of bastardised ‘civility’ and limit on her ability to purchase (on account of being a woman), is, thus, an instrument of the goblins. The hypocrisy with which they invoke civility may constitute a general social ill. The poem says of what the goblins sell, that “Men sell not such in any town.” Of course, these goblins are not in town. The sisters are being lured by perverse ghouls outside of ordinary human community. Indeed, the very fact that no parents are ever mentioned, despite the sisters being young, implies society has left these two women to fend for themselves, for which reason, perhaps, they are being visited by the goblin men, constituting a vulnerable target.

When Lizzie refuses to enter into their arrangement as Laura did, to sit with them and eat with them, the goblins become violent. Lizzie’s resistance, however, is steadfast, and she remains chaste throughout the assault, “Like a royal virgin town:”

Arthur Rackham’s 1933 illustration of Christina Rosetti’s Goblin Market and other Poems.

White and golden Lizzie stood,

Like a lily in a flood,—

Like a rock of blue-vein’d stone

Lash’d by tides obstreperously,—

Like a beacon left alone

In a hoary roaring sea,

Sending up a golden fire,—

Like a fruit-crown’d orange-tree

White with blossoms honey-sweet

Sore beset by wasp and bee,—

Like a royal virgin town

Topp’d with gilded dome and spire

Close beleaguer’d by a fleet

Mad to tug her standard down.

Having failed, they return her money and leave her be. The exchange which they would not accept on Lizzie’s legitimate terms, she refuses on their, illegitimate ones, and so is free of all entanglement and pollution:

At last the evil people,

Worn out by her resistance,

Flung back her penny, kick’d their fruit.

The juices of the fruit which the goblin tormentors throw at Lizzie have no power over her because she never embraces them. Indeed, her inner state of resistance turns these into a substance fit for an altogether different purpose. She returns home to Laura, who kisses her. By this kiss, Laura partakes of the residue of goblin fruit upon Lizzie, so that “Her lips began to scorch, That juice was wormwood to her tongue, She loath’d the feast.”

In the Apocalypse (8:10-11), a star called Wormwood falls from the sky, turning a third of the waters of the earth bitter and causing many to die. This would seem to be an analogous chastisement. What English language Bibles render as “Wormwood” is a translation for the Greek Apsinthos, which is likely a reference to a plant of the Artemisia genus (of which wormwood is a common variety). Their bitter taste, connection to Biblical trials, and medicinal qualities are all consistent with Rossetti’s use of the word “wormwood.”

This chastisement of bitter taste is a fire that overcomes the older fire of sin (fighting fire with fire):

Swift fire spread through her veins, knock’d at her heart,

Met the fire smouldering there

And overbore its lesser flame.

Its nature is repentance, regretting old transgression:

She gorged on bitterness without a name:

Ah! fool, to choose such part

Of soul-consuming care!

Sense fail’d in the mortal strife:

Like the watch-tower of a town

Which an earthquake shatters down.

And so, as with the cross, comes “Life out of death.”

Lizzie has turned the “goblin pulp and goblin dew” into its own antidote, and so Laura’s pitiful state is overcome. The idea of extracting a remedy for poison from the poison itself is perennial. Again, “wormwood” can be medicinal, as well as poisonous. In this case, Lizzie has undergone a scourging like that of Christ, who entered death to remove its sting (to reveal its illusory nature), for her sister’s sake. The Eucharistic element is explicit when she says to Laura, “Eat me, drink me, love me,” for upon her, “forbidden fruit,” as Laura calls it, has turned to medicine. The connection to the Biblical forbidden fruit, then, is clear. The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, whence the fall of Adam and Eve, is reversed by the Eucharistic sacrifice. (Rossetti herself was known to be religious.)

To understand the alchemy at play here, we may refer to the 3rd century Egyptian pagan Zosimos of Panopolis, who was acquainted with, and favourable to, Hebrew scripture. In his writings, Zosimos contrasts the “daughters of men”—who exchanged sex for hidden knowledge from fallen angels in Genesis and The Book of Enoch—with “the Prophetess Isis.” Isis, he tells us, was approached by lustful spirits, but refused their advances, and in this way, was able to command them and so gain secret knowledge all the same, but in a chaste form, rather than a form that overtakes. A thing may be good only if approached well.

The lesson is the same as that of Christian theologians (such as St. Ephrem the Syrian) who maintain that Adam and Eve would have eventually been mature enough to eat the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil and not fall from Eden as a result, if only they had resisted the serpent. Then they would have understood the Knowledge in question, put it in proper context, and applied it righteously.

In Rossetti’s poem (as in Zosimos and the Bible, up to a point), the fruit itself relates to Eros. In the case of Laura, this is wielded by the animal-like, market-goblins, and so takes a vicious form. The antidote is simply Lizzie’s example: learning that sexual pleasure need not be an all-powerful imperative and that resistance to goblinic insistence is possible.

In the Apocalypse, the Tree of Life from Genesis reappears, but not that of Knowledge. Knowledge will never again be sundered from Life. After Genesis, the Bible consistently connects ‘Knowledge of Good and Evil’ to kingship (1 Kings 3:9, 2 Samuel 14:17), presenting it as a virtue. Monarchical imagery is likewise associated with Lizzie. Thanks to her overcoming, she is “Like a fruit-crown’d orange-tree,” and “royal.” When the kings of the nations enter the Holy City in the Apocalypse, cleansing their robes and eating of the fruit of Life, therefore, they are subordinating that Knowledge: it is no longer a distinct tree. The Edenic prohibition, then, was on Knowledge as separate from (as taking precedence over) Life.

The prior duality of these trees is now contained within the Tree of Life (which is described as being on both sides of the banks of a river of living water, and is preceded by two trees, usually interpreted as the law and prophecy—Moses and Elijah—in Apocalypse, 11:4).

Here, we have a necessary reconciliation or balance between opposites: the propriety of Lizzie and the adventurousness of Laura (analogous to law and prophecy), both of which Lizzie must integrate in order to engage the goblins and resist them. Lizzie gains knowledge but does not lose virtue. She redeems Eros by resisting its unworthy form.

That Lizzie turns the goblin fruit into medicine (‘wormwood’) for Laura relates to the medicinal function of the Tree of Life in the Apocalypse 22:2 (“the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations”). We read that the fruits of that tree are for food, whereas its leaves are for healing. In addition, leaves are sometimes connected to pages, that is, scriptures, teachings. The healing would seem, therefore, related to Lizzie’s teaching, that is, the restraint she preached to her sister from the beginning of the poem.

Elsewhere, we learn that the Tree of Life is feminine (Proverbs 3:18). We also read that “the fruit of the righteous is a tree of life, and he who is wise wins souls” (Proverbs 11:30). All of this is perfectly consistent with Rossetti, for Lizzie has been righteous and has won back the soul of her sister, whose “tree of life droop’d from the root” following her encounter with the goblins.

Now, Eros can be properly engaged, always outside the market, whose perverse incentives are a bribe in return for ceasing to perform one’s natural and social duties.

Days, weeks, months, years

Afterwards, when both were wives

With children of their own.

Laura and Lizzie become reconciled to masculine sexuality, receiving fruit from a husband rather than a goblin, rendering themselves fertile rather than entering a state of sterility, as Laura did for a time.

Crucially, Rossetti does not describe this latter. The true fruit of marriage is contrasted to the Goblin Market in that it is not presented to the reader. Its consequences, however, are.

The poem tells us that the lessons they learnt concerning family and striving for one’s sibling’s sake get passed on (just as, in Zosimos, Isis passes on her knowledge to her son, the legitimate king of Egypt, Horus).

The poem believes in redemption. It rejects the idea of permanent defilement that elements of the society in which Rossetti lived (again, a bastardised “civility”) might have upheld. Whatever Laura did, and whatever was done to Lizzie, the sisters do not deny themselves husbands and motherhood.

In this, they correct the sin of a society that left them to fend for themselves, parentless. Having overcome, the sisters end the poem not with their own story, but with the lesson which they have learnt and which they, as matriarchs,pass on to their progeny.

The cure for lethargy, for the depletion that comes from passive (entropic, formless, promiscuous) pleasure-seeking, is active abstention, dominion over pleasure, and the reward for such is pleasure in a form that will not deplete us, being compatible with our spiritual anatomy and human flourishing.