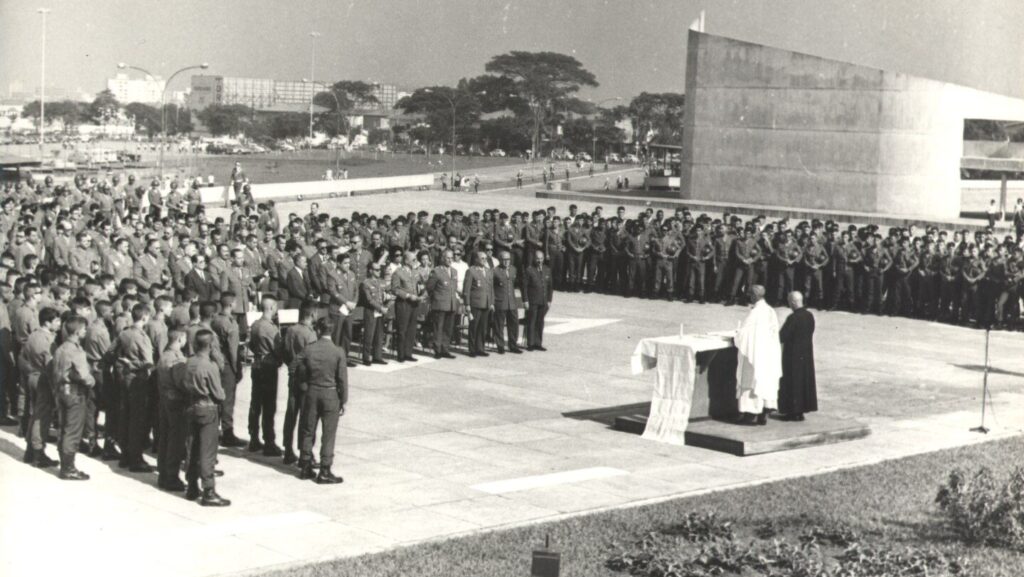

A commemoration of the coup, 1970. Photo courtesy of Brazil’s National Archive

This year, President Lula da Silva has shied away from commemorating or referring to the anniversary of the military uprising. He may not have wanted to be associated with demonstrations that could upset the Armed Forces, which have maintained a legalistic attitude for the last forty years and have not disturbed Lula’s presidency, despite clear abuses against Bolsonaro supporters.

On 31 March 1964, the Brazilian Armed Forces launched a movement that overthrew President João Goulart and ushered in a period of military authoritarianism that would last until 1985. Goulart was Brazil’s vice-president and had taken over the presidency on 25 August 1961, following the resignation of President Jânio Quadros in pre-chaotic circumstances.

Goulart belonged to the PTB—the Brazilian Labour Party, a party of the nationalist Left—and the prospect of his presidency triggered a countermovement on the part of the country’s conservative forces, fearing a drift to the Left. This distrust was shared and supported by important sectors of the armed forces. To prevent a confrontation, a mediation solution was sought that limited the powers of the president, since the Brazilian regime, like the U.S. one, was presidentialist.

Goulart took office on 7 September 1961, but the regime changed to parliamentarianism. The solution didn’t bring stability, and, in 14 months, Brazil had three prime ministers: Tancredo Neves, Brochado da Rocha, and Hermes de Lima. Then it was back to presidentialism.

At the time, the country had a high foreign debt and high inflation. There were also tensions in the countryside in favour of Agrarian Reform. It was the time of the Cold War and, on the American continent, Washington feared the spread of the leftist revolution from Cuba. In this sense, Goulart, who went by the nickname of “Jango,” was seen as too far to the Left. His foreign minister, Santiago Dantas, seemed to be leaning towards a line of third-world neutralism, including rapprochement with the Soviet Union.

In economic policy, the so-called “Basic Reforms” of the Goulart government—agrarian, tax, electoral, banking, and urban reform—determined lines of change that unsettled conservatives and the middle classes, who were fearful of a Cuban-style revolution; this also unsettled Washington.

In September 1963, the situation worsened: a bad economic climate, inflation, worker and peasant unrest. For conservatives, such as the governor of Rio de Janeiro, Carlos Lacerda, the “communist danger” was imminent.

A counter-revolution was also underway in the army, not least because of the Cold War atmosphere and a continental situation in which the threat of Castroism was a major concern. Since the end of the Second World War, Brazil had been a firm ally of the United States. The country had sent the CEB, the Brazilian Expeditionary Corps, to Italy, and in 1949 the Escola Superior de Guerra was created as a military teaching institute open to civilian elites from the public administration and the economic sector. Generals and senior officers attended its courses. The themes and doctrine were realist, anti-communist, interventionist, and security-orientated.

At the same time, the United States was also debating strategies and policies between ideologues and realists, liberals and interventionists. The cases of Bolivia and Guatemala offered opposing examples; in Cuba, the two lines—liberal and hard—had been followed alternatively and successively, but it had gone badly.

John F. Kennedy and his advisers closely followed developments in Brazil. The American ambassador in Brasilia, Lincoln Gordon, advised Kennedy to let the Brazilian military know that Washington would not be hostile to their intervention, should it become necessary, adding that the members of the officer corps were “very friendly to us, very anti-communist, very suspicious of Goulart.”

From the meeting at the White House, it was decided that it would be appropriate to appoint Colonel Vernon Walters, a senior American officer, as military attaché at the American embassy in Brasilia (I met Vernon Walters in the 1980s, a great polyglot who spoke Portuguese really well, with a slight Brazilian accent). He was the right man in the right place, because when he was a lieutenant in Italy, in 1944-1945, he had been a liaison officer with the Brazilians and had met General Castello-Branco and other officers. But Walters always played down his role in the events, beyond the good personal relationship, saying with a sense of humour that the Brazilian military didn’t need the Americans to carry out “coups d’état.”

In developing the alternative policy of le bâton et la carotte, Kennedy had his brother Robert talk to João Goulart, who meanwhile seemed to be increasingly in the hands of the radicals, supported by Leonel Brizola, governor of Rio Grande do Sul. Brizola was Goulart’s brother-in-law, having married his sister, Neusa Goulart, in 1950. But the military conspiracy was underway, with support and impetus from civil society, particularly Catholics and the middle classes of Rio and São Paulo, who were frightened by the radicalisation to the Left. The plans for the uprising were being coordinated by senior officers. The link to the generals was articulated, as in other military revolutions, by civilians. Adonias Filho, a conservative writer and literary critic, told me, in 1975-1976, during my Brazilian exile, the details of this civilian plot that brought General Humberto Castello-Branco, head of the Army general staff, into command of the 31 March coup. Adonias himself, the author of Luanda, Beira, Bahia, had acted as intermediary.

Tensions were rising in March of 1964: on the 13th there was a huge rally in Rio’s Central Station, with Goulart, ministers, union leaders, and sergeants and soldiers present in open rebellion against their bosses; on the 19th there was a response from the Right, with the March of the Family with God for Freedom in Brazil’s major cities; on the 25th, in Rio de Janeiro, it was the turn of the sailors to clash with their commanders. On 30 March, the president tried to calm the situation, but it was too late, and the trump card was now swords. On 31 March, the troops from Minas Gerais, under the command of General Mourão Filho, gave the signal to revolt and began their march on Rio de Janeiro. Throughout the day, the commanding generals of the various armies and military regions exchanged phone calls, but in the late afternoon, General Amaury Kruel, the military commander of São Paulo, abandoned the president and joined the military movement.

Goulart retired to Rio Grande do Sul, while Congress met, declared the presidency vacant and swore in the president of the Chamber of Deputies, Ranieri Mazzilli, as interim president of the republic.

The military movement had triumphed without blood or resistance. João Goulart left the country and took refuge in Uruguay on 3 April. The military assumed power, inspired by a model of authoritarian nationalism; they did not personalise the exercise of that power, as would happen in Chile with Pinochet, but maintained a succession of protagonists from the ranks. General Castello Branco was president from 1964 to 1967; he died in a plane crash and was succeeded by General Artur da Costa e Silva from 1967 to 1969. When Costa e Silva left office due to illness, his successor was General Emílio Médici, who remained in office from 1969 to 1974, being the first military president to serve the full five-year term. He was in turn succeeded by General Ernesto Geisel, who also served the full term and who, with Golbery do Couto e Silva, head of the National Intelligence Service (SNI), began the so-called opening up or distension, despite resistance from the “hard line.” Geisel was succeeded in 1979 by General João Baptista de Figueiredo, who had also previously been head of the SNI. In 1979, Figueiredo decreed an amnesty that allowed many of the exiled politicians to return to the country, re-established the party system—but, of course, exempted the regime’s military and police from blame for abuses.

The Brazilian military regime was justified by its founders and supporters, including former President Jair Bolsonaro, as a state of necessity in the face of what was then seen as the danger of a communist coup. Movements of this kind would be repeated in the subcontinent, in Chile in 1973 and Argentina in 1976: they were seen as an anticipatory defence against what their authors and leaders considered an extreme risk of a communist revolution. In Brazil and Chile, it was a revolution by the Left, with the support of the State’s own leadership: in Argentina, it was radical far-left terrorism, directed specifically against the Armed Forces.

In other words, the military response—and the harshness of the repression—had to do with the radical nature of the threat. The communist danger was, at this time, a real danger, and military action in the bipolarised climate of the Cold War was seen as an exceptional solution, in the manner of the Roman commissarial dictatorship. But the truth is that, in the cases of the large South American countries, the regimes of exception lasted for many years, although in Brazil and Chile they ended by decision of the military themselves.

In the Brazilian case, however, the repression was less brutal than in the Chilean and Argentinian cases. And, at least in the first part of the military regime, it was accompanied by great economic and social progress known as the “Brazilian miracle,” with annual GDP growth rates of more than 10%, major infrastructure works, an acceleration in industrialisation, and the growth of the middle class. The economic miracle ended with the First Oil Shock, which froze many of the benefits acquired and brought Brazil and other South American economies to record levels of foreign debt.

Post-Marxist historiography has insisted on the role of the outside world (the United States, the CIA, and Vernon Walters himself) as the driving force behind the coup, devaluing the national, popular, and religious components. The Marches of the Family with God for Freedom brought together many hundreds of thousands of people in the big cities; Catholics felt offended by Goulart and Brizola, while the military were shocked by the appearance of subordinates and soldiers at demonstrations. Although Washington discreetly supported the military coups, their genesis was national and nationalist.

In politics, the military governments practised authoritarian developmentalist nationalism; in economics, they adopted dirigiste capitalism, with a large public sector and giant public companies like Petrobras. It was a security state, very much centred on preventing and repressing the radicalism of the armed Left. There were some serious abuses which varied from state to state. For example, in São Paulo, home to the 2nd Army, there was more violence than elsewhere. In any case, the list of victims drawn up by the National Truth Commission for opponents killed between 1964 and 1985 puts the number of people killed and disappeared during the military regime at 421. Among these were 70 guerrillas from the so-called Araguaia guerrilla, an armed struggle led by the Communist Party of Brazil, a dissident party of the PCB (Brazilian Communist Party); the latter, the orthodox party, loyal to Moscow, was critical of the armed struggle.

During the military regime, two political parties were allowed between 1966 and 1979: ARENA, with government supporters, and MDB, the tolerated opposition. In 1979, however, an amnesty for politicians was approved, which not only freed and allowed opponents of the regime to return from exile, but also opened up a principle of amnesty for military and police elements involved in repression. To have done otherwise would have jeopardised progress not only towards the democratic transition, but towards civil peace itself.