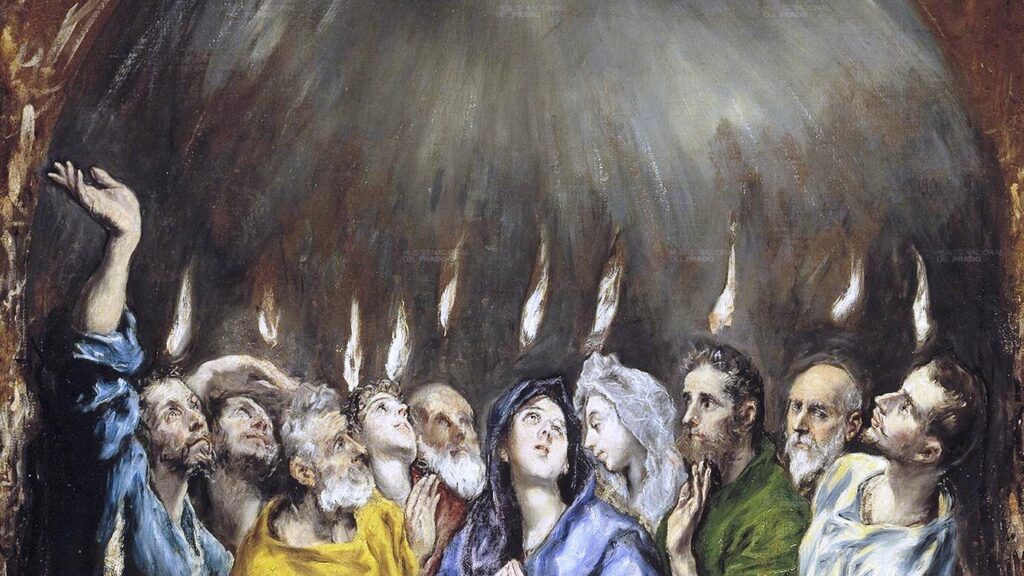

Pentecost (1600), a 275 x 127 cm oil on canvas by El Greco (1541-1614), located at Museo del Prado, Madrid

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

“Whenever the earth shakes, I smell incense,” a priest called Father Anselmo once said to me.

Eventually, I came upon the scripture he was alluding to (I think):

The smoke of the incense, together with the prayers of God’s people, went up before God from the angel’s hand. Then the angel took the censer, filled it with fire from the altar, and hurled it on the earth; and there came peals of thunder, rumblings, flashes of lightning and an earthquake.

—Apocalypse 8:4-5

Apart from his poetic bent, the father—actually an abbot—made an impression on me for his love of Pentecost, which he described as a second Easter.

May 19th will mark the Western Feast of Pentecost this year, when we remember how the ecumene—the human family of nations—was baptised:

And when the day of Pentecost was fully come, they were all with one accord in one place. And suddenly there came a sound from heaven as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting. And there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance … ‘how hear we every man in our own tongue, wherein we were born?’

—Acts 2:1-8

This is said to occur in the upper room of the disciples, which becomes the new Mount Sinai, whence fire from heaven comes to write the law in the hearts of men—not in one tongue this time, but in many.

The number of nations from which those present at the miracle of Pentecost originate can, depending on one’s reading of Acts 2, be tallied as 17. This may be a shorthand for the total number of nations humanity is elsewhere said to consist of, namely 70 (10 + 7 instead of 10 × 7). They stand for the whole human family. The beast that is finally defeated in the Apocalypse, on the other hand, is false unity, the imperial yoke, whence its 7 heads and 10 horns—it parodies the nations. This also suggests that, Biblically, nations are a manifestation of two principles, one represented by the number 7 (the 7 angels in the Apocalypse) and the other by 10.

The apostles are told to “make disciples of the nations.” Thus is the nation the implied constituent of the Church according to the “great commission” in Luke and Mathew. With Pentecost, it comes in greater relief.

We intuitively grasp that cultural diversity has intrinsic value. As St. Thomas writes in the Summa Theologica:

The perfection of the universe requires not only a multitude of individuals, but also diverse kinds … the perfection of the universe … consists in the orderly variety of things … Thus the diversity of creatures does not arise from diversity of merits, but was primarily intended by the prime agent.

And yet, the value of “diversity” is frequently invoked as a battering ram not merely against historical continuity (national identities, for example), but against moral limits (heteronormativity and the like).

We are, in a sense, living a false Pentecost—one that tries to convince us to express the unity of the human condition as uniformity, rather than harmony.

The fragmentation of human community into a slew of “diverse” forms reduces every identity to a consumable product for the atomized individual to wear, and delivers us unto a chaotic uniformity—Hannah Arendt’s “heterogenous uniformity,” which we may understand, symbolically, as the “cup of Babylon” in the Bible and the confusion of those nations with which the whore of Babylon unites.

Pentecost is the assertion of proper diversity, which is taken as an act of violence by forces seeking improper homogenization.

It’s worth remembering that scripture presents Pentecost as a judgement, as well as an exaltation. Indeed, an act of spiritual warfare.

Peter warns as much in Acts 2, following the descent of the tongues of flame, when he quotes the Book of Joel:

And it shall come to pass in the last days, saith God, I will pour out of my Spirit upon all flesh: and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy … And I will shew wonders in heaven above, and signs in the earth beneath; blood, and fire, and vapour of smoke: the sun shall be turned into darkness, and the moon into blood, before the great and notable day of the Lord come.

In Acts 2, Peter identifies the outpouring of the spirit at Pentecost and speaking in tongues as the fulfilment of the prophecy from Joel. But why should the image of disciples speaking many languages be associated with the foreboding elements of the Book of Joel?

Because it is the earthly account of that scene which the Apocalypse (8) describes from its heavenly vantage, wherein an angelic projectile is cast down in judgement.

Indeed, language and national assertion are repeatedly invoked as the means for judging sinful cities in scripture—linguistic attacks marshalled against oppressive uniformity.

It was so during the confusion of tongues at Babel, and again when indecipherable writing appeared mysteriously on the wall at the feasting room of king Belshazzar in Babylonia (Daniel 5), in the context of the stirrings of captive Israelites.

Then, in John’s Apocalypse, we come to a third Babylon. Not the tower of Babel or the historic Babylonian state, but the corrupt authorities of the 1st century: “the great city—which is figuratively called Sodom and Egypt—where also their Lord was crucified” (Apocalypse 11:8). This is the perennial “city of man,” the city that “crucifies the Lord,” that rejects holiness.

Just as the fall of the third Babylon already announced by Jeremiah and Isaiah is set off by a new effusion of tongues—not as confusion this time, but as harmony.

Peter’s quoting of the Book of Joel should also be read in terms of Christ’s Olivet Discourse (Matthew 24 and 25, Mark 13, and Luke 21), that is, as anticipating the destruction of Jerusalem, which came in 70 A.D. Flavius Josephus’ Jewish War (5.5.2.289-300), Tacitus’ Histories (5) and other historians recorded signs in the sky and omens leading up to this event which are consistent with the language used in Gospel and Apocalypse. In fact, Flavius Josephus precisely refers to the feast of Pentecost being interrupted by a man prophesying the coming destruction.

Importantly, the judgement here is also against the Roman Empire, not just the religious authorities at Jerusalem. The Empire (the beast) is also predicted to fall. And again, beyond this, against tyranny and “the city of man,” wherever they might manifest.

The hour cometh when ye shall neither in this mountain, nor yet at Jerusalem, worship the Father … They that worship him must worship Him in spirit and in truth.

—John 4:21-24

Such is the spiritual epiphany that destabilises a corrupt form at Pentecost.

The authorities that claimed a monopoly on the spirit are faced with the (from their chauvinistic vantage) unsettling prospect of a new heavenly dispensation that includes a multitude of languages. Indeed, that the New Testament, as we have it, should come down to us in what seems to be a fruit of Pentecost—a language of pagans, Greek—is a striking, often overlooked sign of this central Christian mystery.

Far from an argument against the originality of the Christian message, an indication of its having been corrupted and of its being fundamentally pseudo-graphic (as some Muslim apologists have claimed), New Testament Greek is an example of an apparently accidental historically contingent medium turning out to be revelatory of the deeper message it conveys.

In Acts 2, the spirit causes disciples to speak in tongues, and that scripture itself is in tongues—in one of those languages that are blessed on the day of Pentecost.

Pentecost, then, is a triumphal declaration of spiritual warfare against that specific catalogue of satanic parodies which the last book of the Bible describes. In particular, we may note two kinds of oppressive uniformity, that of the beast (the Roman Empire in its decadent guise) and that of the whore (Jerusalem in her apostasy).

To Babylon come Pentecostal flames, igniting the embers of a censer cast down from the liturgy of heaven, a missile hurled at the false unity of the Apocalyptic beast and harlot, servants of the dragon, the ancient serpent.

Pentecost resists both the uniformity of political tyranny and of hedonistic cosmopolis, both beast and Babylon, tyranny and mystery, the perverted thymos (θυμός) and eros (ἔρως)—the monoculture of the empire, imposed by military and culture dominance, and the “diversity” of the cosmopolitan society emerging therefrom.

We also read of a false prophet who attempts his own Satanic Pentecost, conjuring “great wonders, so that he makes fire come down from heaven on the earth in the sight of men” (Apocalypse 13:13). This illusion “in the sight of men” is meant to spur up idolatrous worship for the beast, the false unity of tyranny and its ally, false religion.

The history of Christian Europe, then, may be read as bearing the Pentecostal imprint, however imperfect.

It is difficult (for me) to read, for example, Peter H. Wilson’s excellent history of the Holy Roman Empire and not hear an echo of that harmonising choir that began in the blessed upper room, the spontaneous song of praise from the first generation to submit to the One God’s own anointed king, like organs of a body, joyful in themselves and in their contrast, united in their faith.

Wilson describes the territorial demarcation of nations within the Holy Roman Empire as “neither one of progressive fragmentation into ever-smaller territories, nor the steady evolution of existing subdivisions towards sovereign statehood.” Neither the chaos of the cup of Babylon nor the yoke of the beast, but a political order consistent with Christian mutuality:

[The territorial-demarcation of nations] simultaneously embedded the territories more deeply within the [Holy Roman] Empire, because each owed its rights and status through recognition from the other territories. In short, status was mutually agreed rather than self-determined, and thus tied to continued membership of the Empire rather than offering the basis for sovereign independence.

The historic development of nations out of a crumbling Roman Empire, the medieval sprawl of locality, is interpretable as a continuation of Pentecost, as is a certain assertion of the nation against global market-forces and a monoculture breaking with every boundary.

We should pray for Pentecost, I suggest, and remain vigilant against those monsters which are its sworn opponents, according to the scripture.