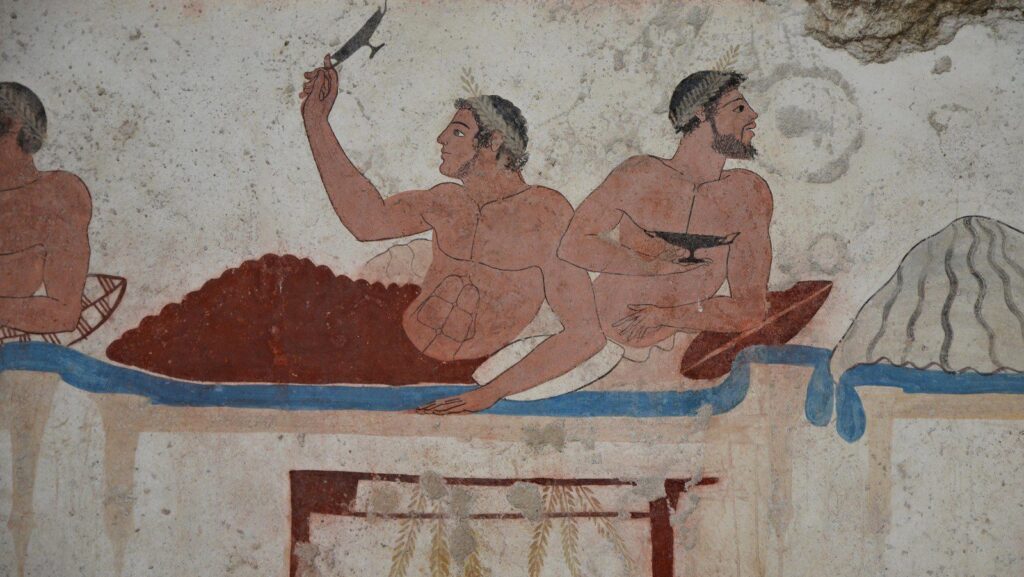

A fresco depicting a symposium (470 BC) by an unknown artist, on the north wall of the Tomb of the Diver in Paestum, Italy. A drinking party of this kind is described in Plato’s most well-known work, the Symposium.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

In his fundamental synthesis, Histoire de l’éducation dans l’Antiquité (History of Education in Antiquity, 1948), Professor Henri-Irénée Marrou demonstrates that, in the Platonic environment, the philosophical life (bios philosophos) necessarily involved the organization of philosophers into fraternities. Marrou uses surviving texts to outline a framework that, although it is specific to the pre-Christian ancient world, nevertheless reminds some authors, such as Antoine Guillaumont and Anton Dumitriu, of Christian monasteries.

Marrou highlights the religious dimension of the Academy, similar to that of the famous Pythagorean fraternity (thíasos) founded by Pythagoras of Samos. As another French historian, Pierre Boyancé, has shown, the school established by Plato and his successors was centered on both the cult of the Muses and the figure of the solar god Apollo. Founded on the friendship (philía) of wisdom lovers, their bond was solidified through festivals organized in a suburb in northern ancient Athens, in the sacred grove of the hero Akademos.

Education of the members of the Platonic school included the master’s discourse, where they imparted their teachings in a gymnasium, and the ‘spiritual exercises,’ (as Pierre Hadot called them) involving the ascetic and intellectual formation of the disciples. Marrou explains that “living in the Academy indeed implied a certain community of life between the master and the disciples, if not simply a collegial organization.” Understanding the communal and dialogic nature of philosophical life within the Academy helps to reveal the profound motivation behind the master-disciple relationship that existed among (neo)Platonic philosophers. Only in this way can we identify the original meanings of the concepts of ‘philosopher’ and ‘philosophy,’ transcending the perpetual confusion in which contemporary thinkers find themselves, as they have failed to propose unambiguous definitions of these terms.

Anton Dumitriu’s reading of Philosophia mirabilis: An Attempt to Unveil an Unknown Dimension of Greek Philosophy (1974) provides a solid starting point regarding philosophical fraternities:

The internal hierarchy of the school, master-disciple, and the methodology of knowledge transmission were, by their very nature, a method of perfecting the disciple, who went through a series of ‘states’ to progress to the state of ‘knower’ and thereby to that of perfection (at which, on the highest step, only very few could arrive).

For the disciple, the initiation into philosophy implied an ontological leap to another level of existence that is superior to the ordinary human condition, a leap based on a philosophical presupposition known since Parmenides: “knowledge has an ontological character.”

The presence of the master is indispensable for the intellectual adequacy of the knowing subject to the object of knowledge–being (tô ón). Only the ‘knower’ can provide knowledge to those who seek it, for such knowledge cannot be conveyed in writing, as is decisively argued in the Phaedrus (fr. 276e-277a):

When one employs the dialectic method and plants and sows in a fitting soul intelligent words which are able to help themselves and him who planted them, which are not fruitless, but yield seed from which there spring up in other minds other words capable of continuing the process for ever, and which make their possessor happy, to the farthest possible limit of human happiness.

Returning to the necessity of the immediate dialogue between master and disciple, the central elements of this philosophical encounter are the words ‘united with knowledge’ (i.e., ‘intelligent words’). However, according to Plato, these words cannot be in written form; only spoken words can transmit wisdom from intellect to intellect within the sacred setting of the Academy. The interpersonal relationship between philosophers cannot be replaced by the relationship between the reader and the text. Such an axiom of the (neo)Platonic tradition cannot be well understood without knowledge of the soteriological meaning of Plato’s philosophy, a meaning that arises from its central purpose: mystical union.

One of the most important contemporary authors who have discussed the profound nature of Plato’s thought is the German philosopher Karl Albert. In his small monograph, Plato’s Concept of Philosophy (1989), he highlighted the deeply religious character of Platonic philosophy, contrasted with interpretations such as those proposed by Martin Heidegger, who conceived philosophy as a perpetual search for truth, a search that finds its conclusion only beyond death. Presenting the ‘metaphysics of the One’ specific to the (neo)Platonic tradition, Albert defines the purpose of philosophy, emphasizing that its ultimate goal is experiential communion with the One. Through this interpretation, he brings philosophical experience closer to mystical experience.

Karl Albert’s position may be supported by a reading of a quasi-mystical passage extracted from Plato’s Seventh Letter (341c–341d). The passage also addresses the true nature of ancient philosophical schools:

Concerning all these writers, or prospective writers, who claim to know the subjects which I seriously study, whether as hearers of mine or of other teachers, or from their own discoveries; it is impossible, in my judgment at least, that these men should understand anything about this subject. There does not exist, nor will there ever exist, any treatise of mine dealing therewith. For it does not at all admit of verbal expression like other studies, but, as a result of continued application to the subject itself and communion therewith, it is brought to birth in the soul on a sudden, as light that is kindled by a leaping spark, and thereafter it nourishes itself.

This passage synthesizes the mystical experience of philosophers that would be perfected by Plotinus and assimilated, in a Christian context, by Saints such as Dionysius the Areopagite, Augustine, and Gregory of Nyssa. What Plato describes here is nothing other than the noetic illumination (i.e., the illumination of the intellect) resulting from the mystical union between the human intellect and the divine intellect, with the latter ‘kindling’ the former. Only in this way can the metaphysical Ideas or Essences be fully known, whose origin and place, according to Saint Augustine, are in the Divine Intellect itself.

However, illumination cannot be achieved without the assistance of the ‘knower’—the Master whose intellect is already in the ‘active’ state (as Aristotle would say). Such an exceptional status can be reached through the “art of shifting or conversion of the soul” (Politeia, 518d) practiced in the context of the Academy, because this art necessarily presupposes the existence of an immediate relationship between lovers of wisdom.

It is in this way that, thanks to the major contribution of Plato, ancient philosophy takes on an increasingly concrete form. Instead of being a mere conceptual construct based on words (as in the case of modern philosophy), the love of wisdom is presented, against the skepticism of Kant and his followers, as an ascent beyond the world of appearances and towards the original realm of essences. More than a way of speaking, then, philosophy is a way of being that requires a suitable way of life aimed at its supreme goal: theōríā (contemplation). That goal is only achievable through that which transcends ordinary existence and forces us into communion with a greater reality: that of a mystical experience itself.