On the 24th of April, at a distance of 1618 years apart, two seminal events in the life of the Church took place.

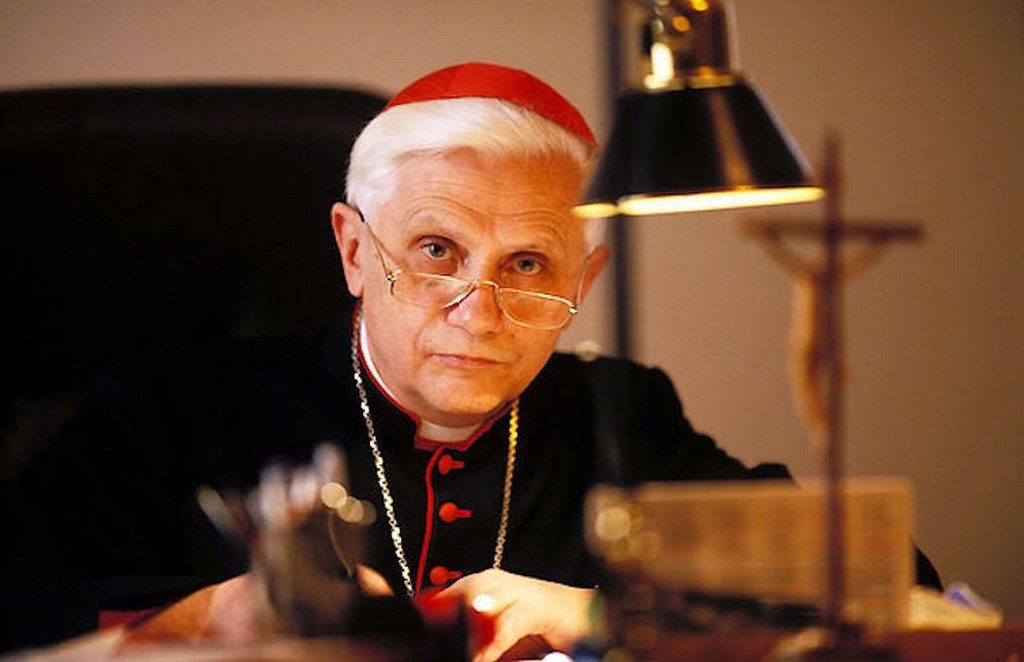

In the year 387, Augustine was baptised and received into the Church by St. Ambrose in Milan. In 2005, the newly-elected Pope Benedict XVI presided over his inauguration Mass.

The day marking the conversion of this saint is propitious. Ratzinger’s affinity with Augustine was prompted by admiration for his penetrating reflection, systematic theology, artistic and literary sensibilities, and the profound quest for wisdom—which came after a stormy youth of polemical exchanges, sexual escapades, and an endless search for meaning.

Both Augustine and Ratzinger were never mediocre. Whatever they pursued, they did so with a certain clarity of mind, openness to dialogue, but firmness of conviction. And both left their mark at a distance of over one millennium. Augustine’s was the most significant conversion since that of Saul on his way to Damascus. Ratzinger’s eight-year pontificate was one long retreat for the Church, helping it to enter an interior cloister of deep reflection and contemplation that, unfortunately, may sometimes be neglected.

An Encounter with Augustine

World War II had, in many ways, unsettled the Ratzinger family, not least the young Joseph. It proved a true test for his vocation and later ministry. After a period of conscription, he deserted the army, and shortly before the end of the war, he was taken into custody by the U.S. army. In The Last Testament, he describes his hardships—having to sleep in the open air, on the bare soil, with no blankets. Moreover, as an aspiring priest, he got a taste of the Church being harassed and, consequently, of also being a possible place of resistance. But, he added, “It was completely clear that after the war, the Catholic Church was first in line to be eliminated by the Nazis, and that she was only still tolerated because they needed all their forces for the war.” After the war, in January 1946, Joseph and his brother Georg could begin their studies in Freising. And it was during this formative period that the encounter with Augustine occurred.

Pope Benedict XVI’s biographer, Peter Seewald, tells us that Ratzinger first came across Augustine’s work at age 19. His discovery of the Confessions marked the beginning of a long and fruitful engagement by the future pontiff with the great Doctor of the Church.

The Confessions is an interesting place to start. The English theologian Henry Chadwick describes the central theme of this book as that of man being alienated from himself:

The soul that has lost God has lost its roots and therefore has lost itself. For the soul is inherently unstable on its own. Because it is created out of nothing, it is mutable; vulnerable to a loss of coherence and unity, to being pulled in a hundred and one directions and so to becoming unable to see below the mere surface of things. Surrender to the tumult of passions renders the soul insensitive to the spiritual dimension which is the soul’s true destiny.

In this great figure of the Church, Ratzinger encountered someone with whom he could identify. As he put it, “a contemporary” and a “true biography” of a “man who was imbued with the tireless desire to find the truth, to seek out what life is, to know how we should live.”

Parallels

In his comprehensive biography of the late pope, Seewald draws parallels between St. Augustine and Benedict. Both were baptised at the Easter Vigil; both had a brother and a sister; both never shied away from entering the great debates of the day; both were reluctant to adopt, as Seewald wrote, “philosophies that did not reach the truth, did not reach God.”

In retrospect, their parallels become more apparent. Both longed to retire to a life of writing and meditation, and both saw themselves unfit for the office they occupied. Moreover, Augustine had no desire to become a bishop, and Ratzinger was equally reluctant to accept the role in 1977. Nevertheless, both had to defend the faith against the heresies of the day, and both believed the world could be renewed, in the words of Seewald, “through a deepening of faith, theology, and holiness.”

To this list, one might add that both seemed to abhor mediocrity in whatever they did.

In successive general audiences at the start of 2008, Pope Benedict gave an excellent catechesis on the significance of the “greatest Father of the Latin Church” who “left a very deep mark on the cultural life of the West and on the whole world.” He argued that “all the roads of Latin Christian literature led to Hippo.” He is the Father of the Church who left the most significant number of works and, Benedict asserted, “civilisation has seldom encountered such a great spirit who was able to assimilate Christianity’s values and exalt its intrinsic wealth, inventing ideas and forms that were to nourish the future generations.”

Augustine is also the Father of the Church who worked on the subject of faith and reason—a question which troubled the learned professor. Benedict notes that Augustine abandoned his faith “as an adolescent because he could no longer discern its reasonableness and rejected a religion that was not, to his mind, also an expression of reason.” Yet, Benedict highlights that Augustine did so with a certain degree of honesty:

His radicalism was such that he could not be satisfied with philosophies that did not go to the truth itself, that did not go to God and to a God who was not only the ultimate cosmological hypothesis but the true God.

In Augustine, Ratzinger found a thinker who believed that the dimensions of faith and reason “should not be separated or placed in opposition; rather, they must always go hand in hand.” He uses the famous Augustinian formula found in Sermon 43:

‘Crede ut intelligas’ (I believe in order to understand)—believing paves the way to crossing the threshold of the truth—but also, and inseparably, ‘intellige ut credas’ (‘I understand, the better to believe’ ), the believer scrutinises the truth to be able to find God and to believe.

People and House of God in Augustine’s Teaching on the Church

Ratzinger’s intellectual trajectory was undoubtedly influenced and made possible through his studies on St. Augustine. His doctoral dissertation, Haus Gottes in Augustins Lehre von der Kirche (People and House of God in Augustine’s Teaching on the Church), was well-received and attracted the attention of his academic contemporaries. The contents of this study would inform many of his later pronouncements on the Church and lead him to a more nuanced and informed understanding of the state and the role of Christianity in the polis.

The result of his research was ground-breaking. Through re-reading Augustine’s work, Ratzinger concluded that the Father of the Church believed that, as he put it, “the Church lived not of its own accord but through the power and grace of the Holy Spirit … It was this uninterrupted action of Christ’s grace that gathered together one people from all over the Earth and gave that people life as a mystical body.”

The God of Faith and the God of Philosophy

As the subject of his first lecture at the University of Bonn—delivered on the 24th of June 1959—Ratzinger chose an eminently Augustinian theme: “The God of Faith and the God of Philosophy.” Later, Benedict explained the rationale behind this choice in the book-length interview, The Last Testament. He writes:

Augustine had not at first been able to start with the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. He had read Cicero enthusiastically, particularly the philosophical speeches. There is in these certainly a keenness for the divine, for the eternal, but no cult, no point of access to God. He looked for that, knowing “I must go to the Bible,”but he was so appalled by the Old Testament that he said “it is not safe.” He felt the contradictions very intensely, and indeed to the disadvantage of the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, because these stories seemed to him to be unbelievable and frivolous. He turned his attention to philosophy, then fell into Manicheism, and only after that discovered what would remain his modus operandi for the rest of his life: “In the Platonist I learned ‘In the beginning was the Word.’ In the Christians I learned, ‘the Word became flesh.’ And it is only thus that the Word came to me.

Ratzinger’s analysis is remarkably prescient in the current situation in various quarters of the Church. On the one hand, there may be a tendency to rationalise arguments to the point where God is removed from the equation. On the other hand, there can be a temptation not to engage with reason and only offer arguments which are, at best, banal. Both are inconsistent with Church tradition, which has always stressed the importance of faith and reason, viewed as the “two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth,” as Pope St. John Paul II wrote in Fides et Ratio.

The Community and the Polis

Ratzinger draws his understanding of three crucial communal expressions from Augustine—the ecclesia (which he addressed in his doctorate), the community, and the polis.

Much of Augustine’s work was conceived in the setting of a community. For example, his conversion is best understood in his interactions with others, be they friends or family members. Most importantly, his intellectual development and thought processes throughout his conversion are best understood through the Cassiciacum dialogues. Ratzinger, in a speech delivered to the Catholic Academy in Bavaria in June 1982, commented on the importance of God-centred communities in the life of Augustine:

We can easily trace the story of Augustine’s conversion in the records of his dialogues with his friends, in which the little academy of Cassiciacum groped its way towards the hour when a new word, which had been unknown to Plato, could at last tumble into its midst and become the beginning of a new life. Analysing these colloquies in retrospect, Augustine concludes that the community of friends was capable of mutual listening and understanding because all of them heeded the interior master, the truth.

In terms of the ecclesial dimension, the work of Michael J.S. Bruno entitled Political Augustinianism succinctly sums up Ratzinger’s views. He identifies in Augustine two realities that “clarify the Church’s role and identity in the world: Christian martyrdom and Pentecost.” Martyrdom symbolises the Church in exile since the martyr “overcomes [popular opinion and imperial power] in faith, in the greater power of God.” The martyr remains an important reminder for the Church to stay “oriented to Christ, even in spite of hardship because of its political nonconformity.” Pentecost, on the other hand, “demonstrates that the Church is not limited by national citizenship or even differences of language” since these are united in communion “in love for the Lord.”

His views on the ecclesial element helped inform his view on the polis and the relationship between the “two cities.” Ratzinger warns against the “clericalisation” or “ecclesiation” of the state and, conversely, on the “nationalisation” of the Church. Both are a necessary presence in the world, but it is only through the Body of Christ that man can be truly transformed.

Nonetheless, Ratzinger “sees no contradiction between the secular state and Christian thought” and rejects the idea of a political theocracy. Instead, he argues that Christians should “live together in freedom with those who hold other beliefs, united by the common moral responsibility founded on human nature, on the nature of justice.”

However, Ratzinger’s acceptance of the secular state is underpinned by a caveat against nihilism:

Ethics alone cannot supply its own rational basis. Even Enlightenment ethics, which still holds our states together, is vitally dependent on the ongoing effects of Christianity, which gave it the foundations of its reasonableness and its inner coherence.

It is through this prism that Ratzinger views the great crisis of the West. This crisis is cultural and is born out of a reluctance to engage with its roots inspired by its classical heritage and Christian tradition. To divorce the West from these roots is to endanger its future. He posits, “The reference of the state to the Christian foundation is indispensable for its continuance as a state, especially if it is supposed to be pluralistic.”

The Purification of the Polis

Most importantly, Ratzinger emphasises the link between truth and tradition. The two should inform one another. This train of thought comes alive in some of his earlier lectures, later translated and printed in the book of collected speeches titled Faith and Politics.

Drawing his examples from classical civilisation, Ratzinger notes that in Rome, “what was contrary to the truth was acceptable for the sake of tradition.” He adds that the “concern for the polis and its well-being justified the violation of truth.” The state, therefore, became self-referential, and its continuation was valued more than the truth. According to Ratzinger, Augustine distinguishes between the Roman and Christian view of state and religion. For Rome, “religion was an institution of the state and, hence, a function of the state. As such, it was subordinate to the state.” Indeed, he adds, “its value was dependent on its serviceability vis-à-vis the state, which was the absolute.”

The Christian understanding, on the other hand, turns this on its head. Custom is subordinate to Truth, and this cannot be instituted by the state. Instead, a community embracing everyone living in God’s truth is formed regardless of the state and its customs. Ratzinger sums it up eloquently: “For Augustine, becoming a Christian essentially meant going from a scattered existence to unity, from the Tower of Babel to the upper room of Pentecost, from the many peoples of the human race to one new people.”

In Augustine’s account of the relationship between the Church and politics, Ratzinger does not see a state dominated by a church or a church dominated by a state, but rather, “in the midst of the structures of this world,” the Church offers “the new power of faith in the unity of men within the body of Christ as an element of a transformation whose ultimate form would be shaped by God himself when history had finally completed its course.”

In other words, Augustine correctly understood the saeculum as time bracketed by God. More importantly, he recognised the limits of the state and the polis—the state cannot encompass the whole of human existence, nor can it hope or aspire to become a totality of things. Ratzinger observes:

The Roman state was wrong and anti-Christian precisely because it wanted to be the totality of human possibilities and hopes. A state that makes such claims cannot fulfil its promises; it thereby falsifies and diminishes man.

By recognising the limits of politics and the state, public officials are in fact unburdened from unreasonable expectations and invited to engage in a politics that does not seek to reach beyond its remit of competence.

Conclusion

Echoes of Ratzinger’s reading of Augustine can best be summed up in his speech at Westminster Hall in September 2010. The limits of the state are implied in the fact that it cannot be the totality of things. Ratzinger, however, adds that religion may have a role to play despite the fact that it is often deliberately excluded from political debates. He maintains that the two cities remain separate: “the role of religion in political debate is not so much to supply these norms, as if they could not be known by non-believers—still less to propose concrete political solutions.” Yet he contends that the role of religion is “to help purify and shed light upon the application of reason to the discovery of objective moral principles.”

On the other hand, religion also requires the purifying role of reason if it is not to be manipulated by ideology and descend into sectarianism and fundamentalism.

Pope Benedict XVI suggests that “the world of reason and the world of faith—the world of secular rationality and the world of religious belief—need one another and should not be afraid to enter into a profound and ongoing dialogue, for the good of our civilisation.”

Over a decade after this speech, it is pertinent observing that his call to a fruitful dialogue of faith and reason was not heeded. Instead, religion is perceived as a “problem for legislators to solve” and has been relegated to the margins rather than seen as a “vital contributor to the national conversation.”

The secularist approach to the complex dialectic of faith and reason, and by extension religion and politics, is not likely to preserve the spheres of the ‘two cities’ but, rather, cause unnecessary friction between the two. Revisiting Augustine and Ratzinger, and studying them side-by-side, shows why such a course is not advisable.