Putting music into words is a difficult undertaking. Even some of history’s greatest authors have left readers with a sort of second hand embarrassment when they attempt to describe music those readers are familiar with. Great music penetrates too far into the realms of the ineffable for even the most poetic descriptions to do it justice. Words are too earthly, and often seem insufficient when it comes to trying to convey higher truths. Where words fail; music begins. That, at its best, is the special power of music and what allows it to rise above other arts.

This power is also expressed in the famous quote attributed to St. Augustine, “he who sings prays twice.” Music is transcendence realised in sound; it is the true language of God, a fact so well expressed in the “Great Music” of the creation story in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Silmarillion.

Mind you, like with all man-made creations, only the best music can live up to this ideal. But they do exist, these pearls of human creativity, through which the divine speaks to us. Some might already be reminded of great symphonies, oratorios, and string quartets, and rightly so! But much of what we consider our canon of Western music is already compromised by countless stylistic boundary-setting and boundary-crossing events.

The starting point of modern listening habits, which shaped the entire occidental music tradition, lies in the time of the Reformation. This, however, includes more than just the contribution of Luther’s followers. The reaction to the Reformation might bear even more historical weight. The reforms of the Council of Trent (1545-1563) gave rise to the music of the Counter-Reformation and thus to the Baroque. It may sound simplistic, but ultimately everything that followed was an inevitable sequence of action and reaction.

The music of the Tridentine period is commonly associated with the work of Giovanni Pierluigi Palestrina, who is often seen as a kind of progenitor of European music. The balance and equilibrium of his counterpoint was stylistically formative and he is still regarded as an ideal example of the Renaissance. It should be mentioned, though, that there was very much a stylistic tradition leading up to Palestrina, and that Josquin des Prez could very well be considered the innovator of many of these forward-looking elements 50 years before Palestrina..

There was, however, also another tradition that came to its end with the Council of Trent. The Council, in fact, emphasized the importance of textual intelligibility; excessive complexity, in which the sung text of liturgical music could no longer be understood (and liturgical music was the be-all and end-all of all music at that time), was frowned upon after the Council of Trent. This was the first musical reaction to the innovations of the Reformers. Following the Tridentine period, music fulfilled a more sensual function for churchgoers, which ultimately resulted in the somewhat carnal splendor of the late Baroque. This means, however, that all post-Tridentine music is de facto reactionary music.

Palestrina’s music, though polyphonic in nature, met the requirements of its day almost perfectly. His themes are intelligible and not exuberant, which has led to his style being taught up to the present as prototypical Renaissance counterpoint.

But there was no musical vacuum before the Council of Trent, even if many contemporary listeners are hardly aware of the tradition that led up to the polyphony of the Tridentine period. Over three centuries, from the beginning of the Notre Dame School, polyphonic music had developed in Europe, reaching a height of expression in the early 16th century that rivals the greatest achievements of the European genius. It was art that didn’t know reactionary thought, unfazed by secular expectations of didactic purposes.

In this pre-reactionary world of music, almost all great music was sacred music, and its authors were mostly priests. This is significant for judging this music not primarily as art, but as sung liturgy, an act purely ordered towards the glory of God. The music of this period should be compared to orthodox liturgies rather than to concert hall music of later centuries—not because it needs to shy away from this comparison artistically, but because we would otherwise deprive it of the intrinsic spirituality which underlies it.

In this purely divinely oriented world of music, after centuries of searching, a breakthrough emerged around the year 1500. A style evolved that was unparalleled in daring and self-confidence, yet was not characterized by human arrogance but by a profound commitment to God. Instead of Josquin’s balanced and poised style, his contemporary Antoine Brumel wrote music that was based on the seemingly endless repetition and variation of tiny musical motifs, motifs piled on top of each other until their microcosmic contributions formed a macrocosm of divine splendor. Nowhere does this become more apparent than in the work of Brumel that literally shook the foundations of the musical world: the 12-part mass “Et ecce terrae motus.”

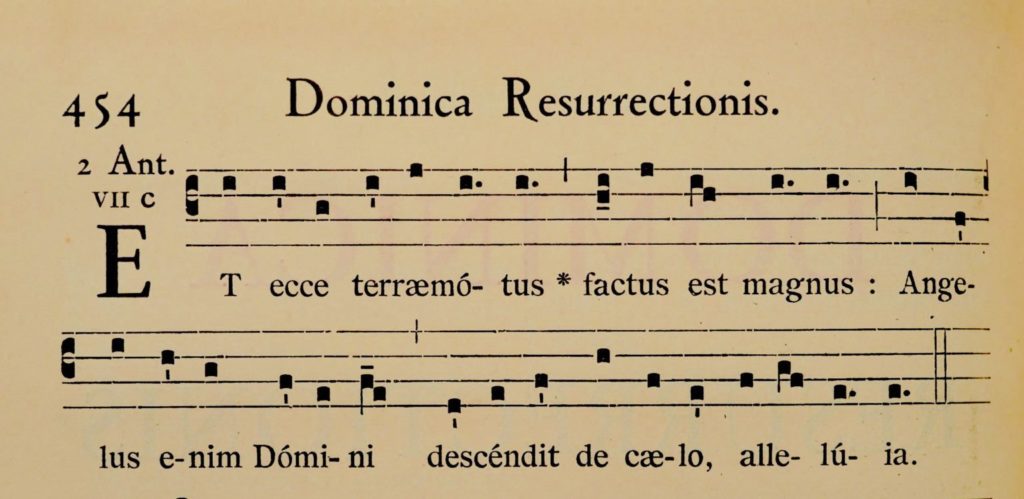

Et ecce terrae motus

factus est et magnus:

angelus autem Domini

descendit de caelo,

alleluia.

And behold, there was

a great earthquake:

for the Angel of the Lord

descended from heaven,

alleluia.

This inconspicuous antiphon from the Lauds of Easter consists of two lines of syllabic Gregorian that revolve primarily around a central tone; Brumel took this antiphon as the basis for writing a mass that surpassed anything ever written before in terms of scope and daring. He only used the first seven notes of the antiphon as a thematic motif—a simpler motif is hardly conceivable—and from this he created a mass that more than lives up to its nickname, the “Earthquake Mass.”

Written around the year 1497, it is symptomatic of the changing world of its time. For long, it was assumed that this mass was heard in 1519 as part of the Leipzig Disputation, during which Martin Luther defended his theses and after which the final break with the Catholic Church took place. More recent conjectures, however, assume that the then Leipzig Thomaskantor had a far more mediocre piece for 12 voices sung at that time instead of the famous work by Brumel. The rest is history.

Instead of relying on refined and balanced voice leading, Brumel created a work whose tonal effect can hardly be described without slipping into platitudes. The best description of this work that I know of comes from musician and author Jeffrey Tucker, who once wrote in a review of this Mass:

What we hear in this stunning work is the musical equivalent of the most elaborate and majestic cathedral… We can easily overlook the music of people like Brumel, which shows no sign of intimidation by the didactic demands of reformation ideology. We find here a freer and more completely unleashed search for God.

Anyone who has heard this mass will undoubtedly understand the analogy of the cathedral. The interplay of the smallest motifs, which are repeated and varied seemingly ad infinitum, with the archaic structure of the Gregorian chant, which forms the architectural pillars of this cathedral of sound in almost seismic shifts, indeed awaken associations with the transcendence of the greatest Gothic cathedrals.

As soon as the first notes sound, it is obvious to the listener that this is not about him and his listening experience, but about God. Far removed from any feelings of envy, we are compelled to fall to our knees in thanksgiving to the Lord for being allowed to participate in this wonder. Every note, every phrase, is an expression of self-forgetting glory, a waterfall of divine grace, opening out to an ocean of paradisiacal sound that crashes upon us in waves over and over again. A “more completely unleashed search for God”—indeed! This is a musical marvel that enraptures our senses, but whose sensual pleasures we never misunderstand as being of our own origin. Our joy comes from participating in this sung praise, allowing for an insight into the infinite glory of God, whose presence is all-encompassing, conveyed in sound from the smallest Gregorian motif to the 12-part giant mass resulting from it.

“Et ecce terrae motus” lets us experience the holy shudder that results from God’s words to Job when he asks him:

Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth? declare, if thou hast understanding.

Who hath laid the measures thereof, if thou knowest? or who hath stretched the line upon it?

Whereupon are the foundations thereof fastened? or who laid the corner stone thereof;

When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy? (Job 38:4-7)

Over the 50 years following Brumel’s composition, a number of composers wrote expansive works for similar large ensembles; Thomas Tallis’s 40-voice “Spem in Alium” is certainly one of the best-known examples of comparable “walls of sound,” but they were mostly parts of a mass or motets. No pre-Tridentine composer other than Brumel ever ventured on a project of this magnitude. After the Council of Trent, music like that of Brumel became unthinkable, and soon the first glimpses of the Baroque appeared on the horizon.

I began by noting how difficult it is to write about music. In turn, I have focused less on the music itself, and more on its function as sung prayer, as a mediator between man and God. This is the true purpose of sacred music, and there are few, if any, works in the history of Western music that fulfill it more radically and uncompromisingly than Brumel’s “Et ecce terrae motus.” It is a musical earthquake, and an earthquake of faith. It shuts off everything egomaniacal in us and focuses us on the divine. It does not want to be admired for its own sake, but to invite us to partake in the eternal praise of the celestial realms. And for this purpose, it could find no better theme than that little Easter antiphon which presents us with the central significance of this, the greatest of days for all Christendom.

Just as Christ redeemed us from our sins by his death on the cross, musical miracles like “Et ecce terrae motus” redeem our situation amidst all the present depravity of our culture. This remarkable achievement comforts us, as it reveals that the adventure of the West was worth embarking upon after all, for it yielded works like these, that shall remain an everlasting tribute to the best in us, realized only when we search for God without ceasing.

Christ is risen! He is truly risen! Happy Easter!