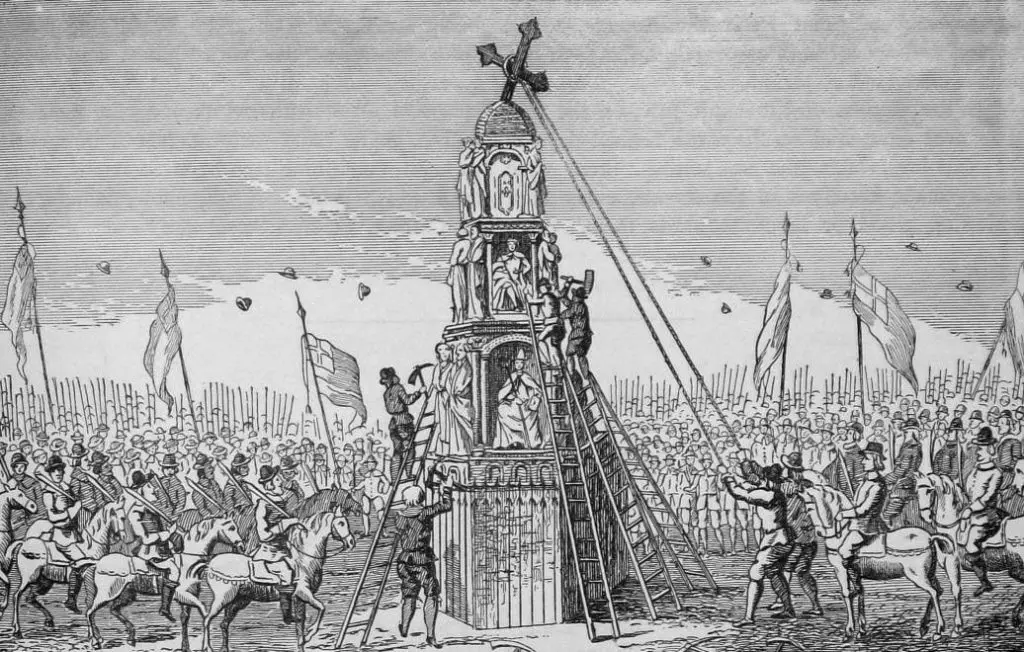

The destruction of Cheapside Cross in May 1643. A huge bonfire was made where the statutes of God, saints, and popes were burnt and melted.

PHOTO: THE EARL OF MANCHESTER’S REGIMENT OF FOOTE.

On the last page of his General Theory, John Maynard Keynes makes a memorable remark about human vanity: “Practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.” He was wrong. The practical men and women to whom Keynes refers are far more likely to be the unknowing agents of deceased theologians than of expired economists. Even in our age of unbelief, Christian theology lies at the root of Western moral life. To a greater or lesser degree, it continues to inform the various views taken up, even by radical secularists, in the political arena.

This audacious idea is defended by the historian Tom Holland in his 2019 book Dominion. Western secular movements, he argues, are not products of pure reason as their supporters flatter themselves to think, but bear the indelible stamp of their Christian origins. Holland struck the same note in a recent lecture about Puritan history and its influence on ‘woke’ activism.

It is useful to think of ‘Wokeism’—a tiresome, overused term—as a sort of neo-Puritanism. No less than early-modern radical followers of the ‘reformed tradition’, the modern Left believes its values to be non-negotiable, insists ferociously on moral purity and condemns monuments to the ‘wrong’ great figures of the past as offensive idols. It also has a tendency to put superficial displays of virtue above real sacrifice, just as John Calvin taught Christians that grace was a gift from God alone, visible only in outward signs that one is predestined for salvation. Puritans rejected the Catholic idea that grace can also be in some measure ‘merited’ by freely performed ‘good works’ as a heretical conceit.

The parallels may be more than coincidental. Indeed, it is striking that the New Puritanism is most contagious in the English-speaking world. It seems to be less popular in historically Catholic countries like France, Italy and Spain. Even the French Revolutionaries, destructive lunatics though they were, did not engage in iconoclasm as such. They were hostile only to icons of the Ancien Régime. After 1789, Jacques-Louis David became the celebrated Michelangelo of la Nation, painting neo-classical tributes to the Revolution’s heroes and martyrs, the new idols of an enlightened Republic. It is also impossible to picture Italians attacking statues of Columbus (the only monuments of the Genoan explorer to have received such treatment are in America) or Spaniards tearing down sculptures of Francisco Pizarro.

Puritanism is not as integral to continental Europe as it has been to the bloodstream of the Anglosphere since the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This likely explains the special ferocity of woke Puritans in Britain, North America and Australasia. The only exception is Switzerland, home to the Geneva once ruled by a Calvinist dictatorship. I was tempted to explain away this seeming anomaly with the get-out that modern Swiss people are just too sensible to re-live this austere, iconoclastic episode in their history. Then I came across a reported outbreak of neo-Puritanism in the country: a campaign to tear down the statue of a Swiss benefactor with ostensible links to slavery.

Before pushing the analogy further, it should be said that ‘Puritanism’ is a contentious term with a nuanced history. In Elizabethan England, it was used as a catch-all tag for extreme Protestants who took their intellectual cues from the most radical theologians of the sixteenth century. These were people who rejected hierarchical ‘priestcraft’ in favour of Luther’s ‘priesthood of all believers.’ They felt that the Church reforms of Elizabeth I, by keeping a prescriptive liturgy, traditional vestments and a clerical hierarchy, had not gone far enough in cleansing the English Reformation of ‘Popery.’ Mockingly dubbed ‘Puritans’ by their opponents, most radically Reformed Protestants preferred in fact, and unsurprisingly, to be called ‘the faithful’ or ‘God’s elect.’

Following Calvin, the Puritans preached that since human beings are inherently fallen, all attempts to commemorate human virtue—be it with statues or saints’ days—were a theft of God’s glory. Calvin proclaimed that the minds of men and women, daring to compete with divine sovereignty, were a “perpetual forge of human idols.” To keep such idolatry in check, Puritans emphasised scripture as the authentic voice of divinity, and condemned the Catholic reliance on sacraments, liturgies and images as supplementary mediators between man and God. Today’s firestorm of iconoclasm is powered by beliefs that Luther and Calvin would surely recognise. There is a politically correct hatred for Western civilisation as its own perpetual forge of human idols, a distinctly Puritan sense that no historical figure is pure enough to merit a statue.

Once some of the more overt Catholic danger was seen off with the defeat of the Spanish Armada, Elizabeth turned on Protestant radicalism within England and Wales, issuing an Act Against Puritans (1593) that came to suspend hundreds of clergy with non-conforming Calvinist sympathies. While this kept the more threatening elements at bay, a Puritan sub-culture continued to flourish in England, particularly in Cambridge, both within and outside the Church (and from the sailing of the Mayflower onwards, in America too). So much so that Puritans later became prominent in the Parliamentary rebellion against King Charles I’s personal rule. Indeed, one reason why Puritans suspected Charles of ‘popery’ was his connoisseurship of flamboyant continental art, much of it religious in a Catholic sense, especially painting and sculpture. (His great collection, deemed idolatrous, was sold off after his execution in 1649.)

However, the puritanically-minded were more alarmed by the King’s appointment in 1633 of William Laud—already Bishop of London—as Archbishop of Canterbury. To the Puritans, Laud’s ecclesiastical reforms—striving to achieve ‘the beauty of holiness’ in places of worship and moving the Communion table to the east end of parish Churches—looked part of a Romanist plot to undo the Reformation. This was made worse when Laud started cracking down on Puritan practices within the Church, forcing vestments on all clergy and requiring laymen to kneel to receive Communion.

Once the Puritans rose to power, they set about putting their iconoclastic ideas into practice. Parliament ordered Churchwardens in 1641 to reverse ‘Laudian’ innovations by removing communion rails, altars, crucifixes and icons of saints. Two years later, a parliamentary ordinance stated that “all Monuments of Superstition and Idolatry should be removed or abolished.” One man who took this especially seriously was William Dowsing, a Puritan provost in East Anglia. In one of his diary entries, dated January 1644, Dowsing records an honest day’s work as a religious vandal: “We broke down about a hundred superstitious Pictures; and seven Fryars hugging a Nunn; and the Picture of God and Christ; and divers others very superstitious; and 200 had been broke down before I came. We took away 2 popish Inscriptions with Ora pro nobis and we beat down a great stoneing Cross on the top of the Church.” There are no doubt many wokesters today who will recall their own destructive exploits, be it against Churchill or Columbus, with a like sense of pride (though old-school Puritans would never have used that word).

But as one probes deeper, the shortcomings of the analogy begin to seem more illuminating than its merits. There is plenty to admire in the old Puritans. They were serious people who stressed the relationship of the individual to God. They emphasized virtuous self-rule and ethical responsibilities. These evidently Christian aspects of the early-modern Puritans are conspicuously missing from the half-educated rantings of their woke successors. The New Puritans are holier-than-thou, they worship appetite at the expense of self-restraint and any notion of personal responsibility gets lost in neo-Marxist rhetoric about ‘systems of power’ and ‘oppressive structures.’

Old Puritanism was not always sophisticated. One recalls Daniel Defoe’s remark about the intellectual calibre of many Puritan types: “the streets of London are full of stout fellows prepared to fight to the death against Popery, without knowing whether it be a man or a horse.” The same can be said against many of the New Puritans, who wrongly equate slavery with colonialism and would no doubt struggle if invited to guess who said the following in 1906: “We will endeavour… to advance the principle of equal rights of civilized men irrespective of colour.” It was that notorious racist psychopath, Winston Churchill.

But the New Puritans take stupidity to new heights. It could not be clearer, for example, that for all their fighting talk against moral impurity, the radical left is more than happy to kneel before idols, so long as they are the ‘right’ ones. The most recent case involves a school in Richmond, which decided to remove ‘Churchill’ and ‘J.K. Rowling’ from the names of their school houses. Luther and Calvin would certainly applaud this attack on two monuments to human pride—except that the houses were then renamed in honour of the ‘more diverse’ progressive icons, Marcus Rashford and Mary Seacole. The woke Puritans lack the moral consistency of their Christian forebears. They make for a very frivolous new elect—lack of seriousness being the last thing conveyed by Oliver Cromwell’s ugly visage.

Moreover, the old Puritans viewed themselves as traditional warriors on behalf of the early Church and Old Testament laws against idolatry. Woke activists are nothing like this. Their battle cries are not situated within a clearly defined moral framework or tradition. G.K. Chesterton defined heresy as “a truth taught out of proportion.” By magnifying certain bits of the Judaeo-Christian corpus at the expense of others, old-fashioned Puritans could at least be attacked as heretics. Lacking any such tradition or an authoritative source of truth, the New Puritanism cannot even be paid this half-compliment of heresy. It is not a re-run or even a selective distortion of Christian principles. Rather, woke ideology acts as a parasite on core Christian doctrines, like equality and the law against idols, which it then turns to a vaguely Marxist end: the struggle for political power in this life, so that History can progress to full enlightenment.

Crucially, Puritans believed original sin to be a serious problem, universal to mankind, and subjected themselves as much as anyone else to a rigorous examination of their moral shortcomings. For the New Puritans, fed on neo-Marxist theory, other people and identity groups—or more vaguely still, invisible “power systems”—are the real problem. Shallow declarations of privilege or victimhood, depending on where one lands in the intersectional hierarchy, are all it takes to join the ranks of the elect.

This fuels a fundamental intolerance, which Holland in his lecture suggests may be partly explained by the woke Puritans’ embrace of Pelagianism. Pelagius was a fourth century theologian who took issue with St. Augustine’s view that sin is a brute fact of the human condition. Pelagius argued instead that it was within our power to rise above original sin to achieve self-perfection. Redemption in Christ was replaced by a human striving to create Heaven on earth, in rather the same way advocated by Marx and other political idealists.

As for the absence of forgiveness from modern cancel culture, Holland says: “If you can redeem yourself from sin,” as Pelagius taught, “that means there can’t be much sympathy for those who fail to do it.” If sin is not integral to our nature, but can be overcome by putting the right words in a Twitter bio, then it is easy to spit on the flawed heroes of history and to condemn people who, even today, refuse to limit their thinking to authorized progressive slogans. St. Augustine was both more pessimistic and yet more charitable. Sin was not an external thing to be casually denounced, but an inner reality for every individual to contend with—the line between good and evil being one that runs through every human heart, as Solzhenitsyn later put it. Ultimately, our fallen nature requires a salvation that we cannot generate for ourselves. But liberal culture has thrown out Augustine’s reliance on Christ’s mercy in favour of Pelagian self-perfection. One of the results is a neo-Marxist lookalike of Puritanism, full of simple-minded intolerance for anyone who fails its purity tests.

The New Puritans feign an aversion to pride and idols only insofar as it serves their political ends. They should be rejected as menacing imposters. But we should also reject a more sincere application of Puritan principles. Most people are sensible enough to understand that celebrating great deeds does not mean making men into false gods. Puritanism leads to bland public spaces and less inspired national lives, emptied of their most important characters and memories. If the neo-Marxist version is indulged, we will soon discover what happens to cultures which benefit from the lives of dead heroes, but refuse to acknowledge their debts.