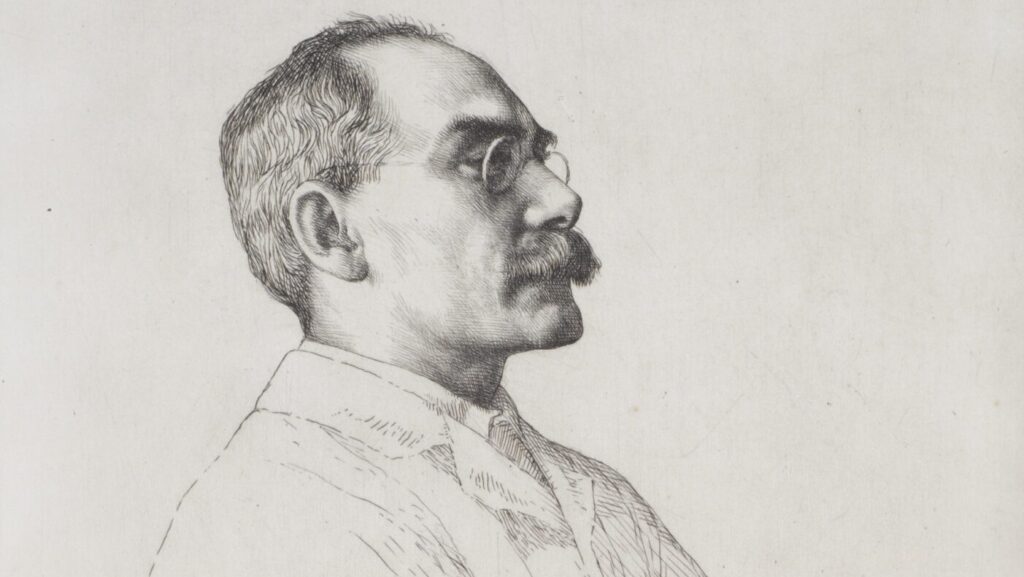

Rudyard Kipling, No. 1, 1898, England, by William Strang. Gift of Sir John Ilott, 1956. Te Papa (1956-0001-17)

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

In Christianity or Europe, Novalis writes that, “What had been lost in Europe, they sought to regain in many quarters of the world.” According to Virgil’s Aeneid, when survivors from the fallen city of Troy settled on Italian soil, their journey’s end was not merely a venture into new lands—it was a return: not an Iliad, but an Odyssey, a homecoming.

Virgil tells us that the Trojans were descendants of one Dardanus, an ancient Italic patriarch who had migrated to Anatolia in antiquity. Once home, the embattled wanderers were instructed to become what they already were: indigenous, adopting the language and customs of their long-lost brethren, the local Latins. They were, however, permitted to bring over certain elements from their centuries-long Asian sojourn. These included the sacred Palladium, a meteoric stone fallen from heaven (according to Dionysus of Halicarnassus), destined to become Rome’s own Kaaba, eventually placed in the city’s Vestal Temple.

Rudyard Kipling was foremost among Britain’s authors of empire: a man born and raised in India who never reneged on the British imperial project. When he arrived at his native Albion, it was, in some ways, as a returning Trojan. Although he is known as the author of “The White Man’s Burden”—a strange text that reads like a satire despite (apparently) being nothing of the sort—Kipling was marked by India. Like the Trojans, that which he brought back, and which he shares with readers throughout his varied works, is a peculiar spiritual imprint.

A committed Freemason (possibly the most prominent Masonic artist after Mozart), he nonetheless did not share the Deism through which many of his brothers interpreted the ‘craft’ during the 18th and 19th centuries. Unlike the Deists, Kipling believed in a God very much present to human beings and history: God is the “dispenser of events,” he writes, quoting from the Quran in his autobiography Something of Myself.

Kipling’s understanding of king Solomon’s Table—of the secret of the original Jerusalem Temple at the heart of Freemasonry’s mythology—was suffused with the traditions of the subcontinent, making for a specifically British imperial compact. Among these traditions, the most prominent is Islam. This is the Asian Palladium Kipling brings into British literature and consciousness. He belongs to that current of modern European authors that expressed admiration for the religion of the Arabian prophet—Nietzsche, Carlyle, Goethe—albeit distinguishing himself for being less spurious than most of them in his treatment of religion.

In a work like “The Enemies to Each Other,” where Kipling is at his most oracular—what we may describe as his myth-making mode—he repeatedly alludes to Quranic images and Muslim theological formulae. It reads like certain texts by the 12th century Sufi ibn-Arabi, or the latter’s modern disciple and father of Algerian independence (and probably Kipling’s fellow Freemason) Emir Abd al-Kader.

“The Enemies to Each Other” is, among other things, a quirky meditation on how marital bickering is a blessing, for, by means of it, men and women keep each other honest and away from self-worship. A crucial point in its narrative comes when Adam, having set himself up as a god, abandons his pretence following an argument with Eve, who had done likewise (in part to spite him):

Then by the operation of the Mercy of Allah, the string was loosed in the throat of our First Substitute [Adam] and the oppression was lifted from his lungs and he laughed without cessation and said: ‘By Allah, I am no God but the mate of this most detestable Woman whom I love, and who is necessary to me beyond all the necessities.’

Beyond the work’s immediate context, the rejection of worship of a ‘visible god’ might be a reference to Christianity. We may consider a letter sent to Miss Caroline Taylor, dated December 9, 1889, in which Kipling reveals his creed (such as he held to at the time, at least):

Chiefly I believe in the existence of a personal God to whom we are personally responsible for wrong doing … I disbelieve directly in eternal punishment … I disbelieve in an eternal reward… Summarized it comes to I believe in God the Father Almighty Maker of Heaven and Earth and in one filled with His spirit who did voluntarily die in the belief that the human race would be spiritually bettered thereby.

Leaving aside his disbelief in an eternal reward, what we have here is a unitarian theology and a low (possibly Arianist) Christology. In fact, low Christology turns out to be of a piece with his concept of empire and with his ecumenism. Kipling seems to understand God’s transcendence with respect to created forms as making it impossible to identify the Divine presence with any one particular historical event (such as the Incarnation).

“Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,” writes Kipling in the opening line of “The Ballad of East and West,” which has been read as a sort of acceptance that the stereotyped categories of Western rationality and Eastern mysticism are not synthesizable. And yet, in “The Two-Sided Man,” we have an invocation of Him who made both halves. Kipling does not champion Western rationality, nor oriental mysticism in some oneiric sense, but wants instead to invoke the Maker of both, for whom he settles on the name of Allah:

Much I reflect on the Good and the True

In the Faiths beneath the sun,

But most upon Allah Who gave me two

Sides to my head, not one.Wesley’s following, Calvin’s flock,

White or yellow or bronze,

Shaman, Ju-ju or Angekok,

Minister, Mukamuk, Bonze—Here is a health, my brothers, to you,

However your prayers are said,

And praised be Allah Who gave me two

Separate sides to my head!

Here, divine transcendence is the principle according to which all earthly religions can be arranged on a plane, equidistant from the divine One, so to speak. And this, I would suggest, is not unrelated to his affection for empire.

It could be that, in Kipling’s mind, the relativizing of different traditions (“… my brothers, to you / However your prayers are said”) within a wider harmony of the common worship of God could be satisfactorily manifested in a political project like the British empire. Although, to honour such an insight, such an empire would need to be decentralized and not privilege one cultural or national community over others. This would be consistent with the affectionate way in which he treats all the various ethnicities depicted in the novel Kim, in which a Lahore-enculturated European boy ultimately finds that he cannot cease to be European.

Although the West and the East will not meet (that is, they will not cease to be opposite poles, opposite sides of one head), iron can nonetheless sharpen iron, even as Adam and Eve kept each other from self-worship. Kipling’s point seems to be that, by virtue of a certain British way of being (including European rationality), the empire will influence the cultures it touches into shedding spurious elements.

Towards the beginning of Kim, we find the following warning concerning the tendency of religion to accrue superstition and speculation: “I come here alone … it was in my mind that the Old Law was not well followed; being overlaid, as thou knowest, with devildom, charms, and idolatry … So it comes with all faiths.” As I read him, it is in correcting this “overlay” of “devildom, charms, and idolatry” that Kipling finds the British imperial enterprise resonant with the simplicity of Islam.

Kipling understands empire as a coordination of different cultural spaces, an ecumenical harmony between faiths that helps them shed their idolatry through the contagion of a rationality that is not ultimately materialistic or utilitarian but metaphysical and unitarian. And the Masonic lodge, as a non-religious—yet religious—structure, whose central image is that of the construction of a temple through practical, technical knowledge (the symbol of the compass, etc.), becomes the vehicle for advancing this project.

Of course, the British Empire didn’t actually function according to Kipling’s poetic vision; it’s up to each reader of his work—and each student of the empire’s ambiguous history—to determine how much of this constellation of ideas is positive and can be integrated with one’s own political and religious convictions. But it is worth remembering the point gleamed from Kipling’s work: that empire always transforms the culture (in this case the literature) of the conquering people, that colonies often lead to Trojan return, and that Trojans often bring a Palladium.