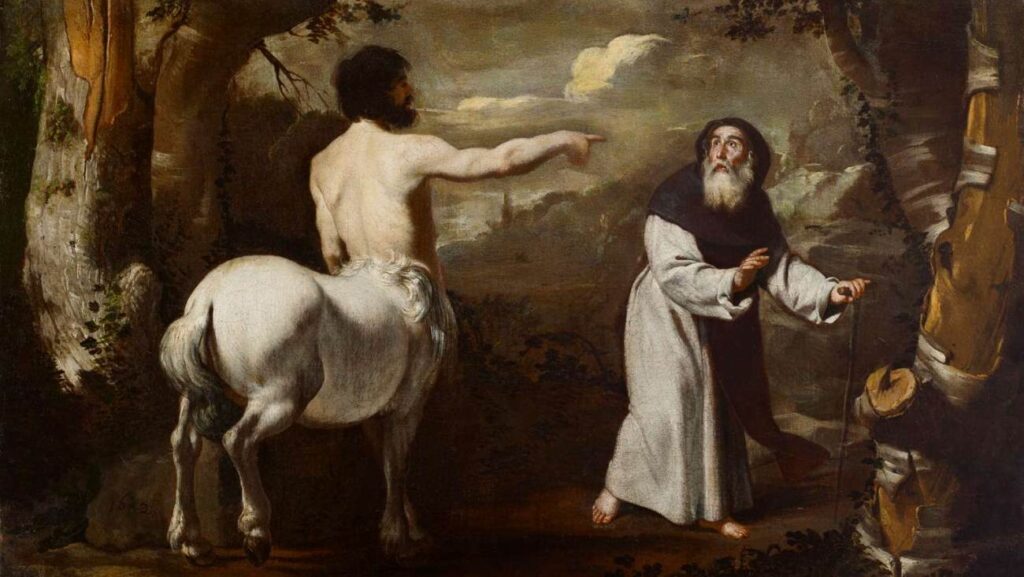

St. Anthony Abbot and the Centaur (1642), a 40 x 66 cm oil on canvas by Francesco Guarino (1611-1654), private collection.

In St. Jerome’s Life of Paulus the First Hermit, written in the second half of the fourth century, we read the following about St. Anthony’s encounter with what seems to have been a Christian faun or satyr:

Before long, in a small, rocky valley shut in on all sides, he sees a mannikin with hooked snout, horned forehead, and extremities like goat’s feet. When he saw this, Anthony, like a good soldier, seized the shield of faith and the helmet of hope: The creature, nonetheless, began to offer him the fruit of the palm tree to support him on his journey and as it were, pledges of peace. Anthony, perceiving this, stopped and asked who he was. The answer he received from him was this:

I am a mortal being and one of the inhabitants of the Desert whom the Gentiles deluded by various forms of error worship under the names of Fauns, Satyrs, and Incubi. I am sent to represent my tribe. We pray you in [Sic] our behalf to entreat the favour of your Lord, and ours, who, we have learnt, came once to save the world and whose sound has gone forth into all the earth.

We often hear that Christianity reduces the unseen realm to either angelic or demonic, having no room for the ‘fairy-folk’ the way, for example, Islam teaches that there are both evil and Muslim genies (jinn). Given the above and similar accounts, it would seem this is not the case.

What is particularly significant about St. Anthony’s encounter, however, is that the form of the faun in question, namely its goat-like appearance, is, in a Christian context, traditionally considered a symbol for sinful inclinations. Indeed, a hoof-footed, animal-legged man became the depiction of choice for the devil himself.

That such a being should exist and retain this form while professing the true Faith and even seeking to entreat itself and its kinsmen to the God of Scripture implies that the chimeral shape in question should receive a different, righteous meaning—should become symbolic for some virtue rather than vice. And even if the shape of the satyr were irrevocably linked to sin, we could yet imagine its redeemed version.

The Book of Enoch (8), congruent with Genesis 6, tells us that weapons of war originated with the Nephilim, agents of corruption that taught our distant ancestors to forge blades and the like. Yet the prophet Jeremiah will reveal that there may be an armoury in the heavenly realms when he appears to Judah Maccabee and gives him a shining paradisiacal sword with which to wage his campaign (2 Maccabees 15:15-16).

In fact, much of the knowledge dispensed by unclean spirits in the Bible, we later discern, was problematic on account of coming to us during the wrong season and in the wrong way, but is, in itself, part of mankind’s birthright and can be used in the service of God.

This idea comes through in scriptures like “Ye thought evil against me; but God meant it unto good” (Genesis 50:20) and “for those who love God all things work together for good” (Romans 8:28).

Even the “knowledge of good and evil” is ultimately the cause of the fall because that knowledge is obtained through disobedience and through a tree perceived to be separate from the Tree of Life in the Garden of Eden. Later in the Bible, however, such knowledge of good and evil is praised, considered necessary, and appears ultimately to be rectified by the New Jerusalem in John’s Apocalypse, where there is only the Tree of Life.

The forms that develop through the fall and sin belong to a righteous end: there is no such thing as a righteous murderer, but there is such a thing as a Christian soldier, just as there is no such thing as a friendly demon, but there is, apparently, such a thing as a Christian satyr; there is no sinless fornicator, but we have a model for pious eros in the Song of Songs; demons may have taught us to forge, but Judah wielded a heavenly sword.

Just before Halloween, my two-year-old niece spontaneously began playing a game in which she would have me pretend to be a fearsome wolf, run away excitedly, and then, girding her courage, offer the wolf an invisible morsel of human food. At this point, the wolf would be free of hunger and, specifically, it would be liberated from the impulse to munch on humans.

Alternatively, she would pretend to hear the howling of wolves outside, in the nearby forest, when the sun went down, and offer them some food through the window, observing that the wolves had, thereupon, become friendly.

The meaning of the ‘trick-or-treat’ ritual may be found here. It is not only that the ‘trick’ (of being eaten by a wolf, in this case) is avoided through a ‘treat’ that wards off the beast.

Rather—crucially—the ‘treat’ transforms the ‘trick.’

The wolf becomes part of the human circle after partaking in human food (specifically “focaccia”—my niece is Italian, but the significance of bread in this transformative meal should be highlighted).

Thereafter, the howling outside is not a sound from beyond the bounds of human community but is reinscribed as the perimeter of that community, with the wolf being a guardian rather than a besieger. We have in this child’s game a recapitulation of the foundational domestication of the wolf.

No more wolf, but dog; no murderers, but warriors; no fornication, but the garden of the Song of Songs; no demons, but Christian satyrs; just as in the New Earth, there is no more sea, but rivers and lakes (Apocalypse 21:1; c.f. Ezekiel 47:9).

We may describe the supernatural beings whose costume likenesses clamour about on Halloween as the ‘fay,’ ‘fairy-folk,’ or ‘spirits.’ Apart from denoting a kind of ordinarily invisible creature, however, the traditions dealing with the many shapes and behaviour patterns of the “fairies’ are also clearly describing parts and potentials of the human personality itself. Separately from the existence of unseen intelligences, we are also dealing with projections of our own human soul.

To have a tribe from among these come in search of guidance in orienting itself towards the proper worship of God, per St. Anthony, or to have a ferocious entity from that realm come to us for food and so transform from dangerous wolf to guardian dog, per my niece, is to expand the human circle. The dominion of the righteous will, the hearth as spiritual polity, widens to integrate parts of ourselves that have grown unruly, even quasi-demonic.

Such, then, is one meaning of Halloween (and Carnival) and of the fairies in folklore in general.

Before discounting Halloween as pagan or devilish, we should attend to its deeper significance.

In fact, I would suggest that the image of St. Anthony and the satyr (or his other encounter with a centaur, of which we are also told in Anthony’s hagiography and which is depicted by painter Francesco Guarino) is one of those images waiting to be reclaimed, an emblem of repressed orthodoxy by which believers might refresh, recover, and (in a certain sense) radicalise the culture at large.