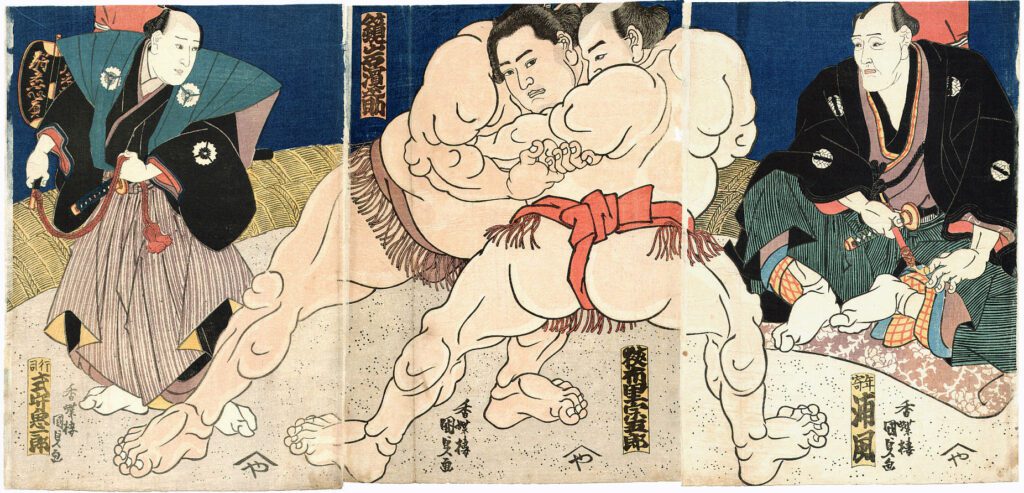

“Sumo wrestling, three pieces, full view: two wrestlers during a bout. left side: a gyoji (referee) carrying a wooden war-fan, right side: a shimpan (umpire)” (1840s), colour woodcut triptych by Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1865), location unknown.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Wrestlers clad in ceremonial mawashi loincloths step into the purified soil of the dohyo. Salt is swung into the arena, banishing untoward influences from the space.

A raised platform of clay is matted down and consecrated under the easy yoke of reverence borne by the warrior-heirs to centuries of tradition.

Shinto priests raise the names of kami spirits so that their ethereal presence might be rendered palpable to the hushed crowd as they invisibly join the human spectators. Drums are pounded.

The wrestlers bow, their every gesture paying homage.

As with the sky and earth gods said to have inaugurated the sport of sumo, the bodies of the wrestlers are meant to balance apparently opposed forces: power and prowess; a frame at once capable of explosive forward advance and the agility of judo-like reversals.

It all began with Takemikazuchi and his earthly counterpart, Takeminakata. These both belong to a lower order of deities in Japanese mythology. Takemikazuchi, for his part, is a thunder god born from the blood of a slain fire god, whereas Takeminakata is also a warrior but is regarded as an earthly deity, presiding over agriculture, wind, and water.

The foundational wrestling match between them is extremely significant, as it relates to the widespread theme of a non-human war that once engulfed the cosmos before recorded history proper. We may think of the conflict from which Takemikazuchi was born, in which the higher gods slew rebellious demons, as equivalent to the war between Olympians and Titans in Greek mythology, Aesir and giants in Norse accounts, and the angelic casting down of Lucifer and his demons in the Biblical worldview.

Following the victory of the angels or gods, however, the earth and nature were in a state of chaos and had to be brought to order. Enter Takemikazuchi, who was deployed by the celestials when they decided to conquer our mortal realm, called “Middle Earth” (Ashihara no Nakatsukuni, like the Norse Midgard).

Crucially, however, such conquest was not to be unilateral but would have to make room for earthly nature and find a way to harmonise apparently conflicting forces—including those of the sky and earth.

When Takemikazuchi descended he asked that a local deity called Ōkuninushi relinquish his realm, but one of Ōkuninushi’s children, Takeminakata, refused. Therefore, the first sumo match commenced between Takemikazuchi and Takeminakata.

The latter, earthly, deity was defeated but received a position of honour all the same. Takemikazuchi then went on to aid Emperor Jimmu in his conquests, helping establish a politically pacified human dominion.

The similarity between the names of Takemikazuchi and Takeminakata points to them representing corresponding principles. Importantly, neither are human. Rather, they are cosmic agents who organise the world and whose balance benefits humanity.

The nature of this balance between celestial angelic forces and earthly natural ones is such that, even when there is apparent conflict, they must acknowledge each other. This is crucial to understanding sumo.

In sumo, both wrestlers have to place their hands on the ground in front of them before the match can begin. This requires some coordination between them, as both want to do so from a position of stability and readiness and know that as soon as their opponent’s hands are likewise placed, they will get only a fraction of a second to react.

A few years ago, Mongolian sumo wrestler Hakuhō Shō—who is considered one of the best of all time—faced off against Takayasu Akira in a match marred by a protracted false start on account of Takayasu hesitating to place his hands down (for an excellent discussion of this, see this video).

The episode provides a good example of how subtle the understanding that must exist between wrestlers in order for their match to start is and how easily it can be disturbed. There is no third party deciding when the two fight—the exact moment at which a match begins is determined by the competitors themselves, through their actions.

Civilised conflict requires coordination and prior agreement. If we consider the origin myth of sumo, we may reflect on how the war between the celestial and earthly realms was tamed by the sport and turned into an arena structured by higher principles.

Like the suggestion that we begin marking the fall of Troy in June in order to remind ourselves that, as a civilization, we are still heirs to Rome and the Trojan exiles who founded her, I would propose the above as material for the sacralization of competitive martial arts beyond Japan.

Mechanically, any modern combat sport would have to be a species of mixed martial arts (we can’t pretend we don’t now know that an average mixed martial artist can defeat most black belts in older, highly limited systems), but the specific rules and overarching ritualism could be tuned to transmit a reverential ethos.

In Europe, Greco-Roman wrestling could be reimagined—its Takemikazuchi and Takeminakata could be Apollo and Python, the solar hero-god and the chthonic serpent-spirit, who struck a balance such that Apollo’s oracle was established at the site of Python’s dwelling place.

As Novalis wrote, all tradition is invented, and Europe and the West are in need of a renewed folklore, as well as of symbols for conciliation through conflict.