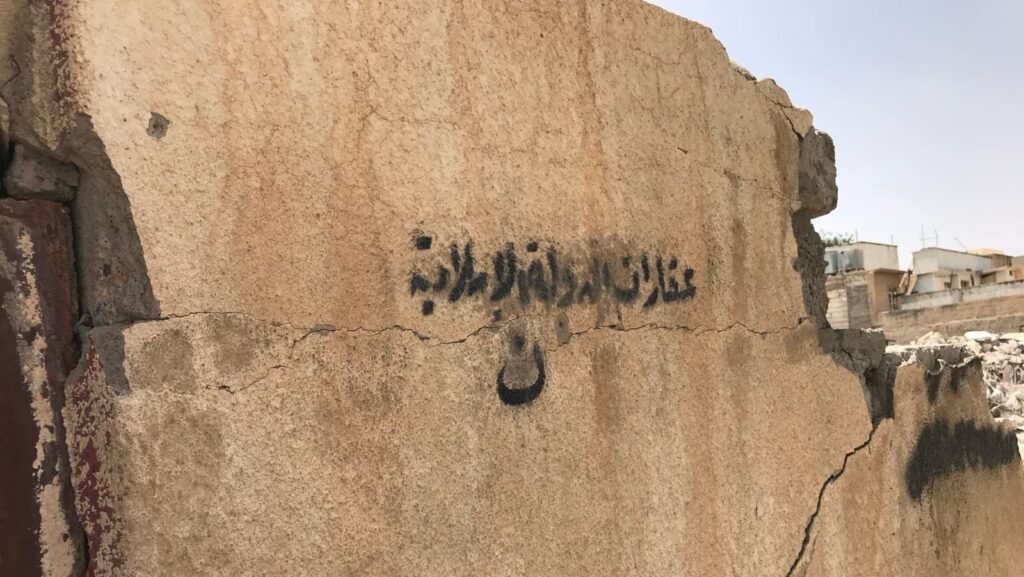

Photo taken by the author of a destroyed church in Mosul with graffiti reading “property of the Islamic State.”

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

Even though it was a friendly jibe as we drove over the oldest bridge into Mosul, being blamed for the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement, and all the ensuing problems that Iraq had endured for the next hundred years was, I felt, stretching collective British and French colonial guilt a little bit, at least in my mind.

As the Islamic State’s Caliphate had just been driven out, it was time, on the latest of my many visits to Iraq to help the ancient Christian community, to see if any Christians could safely return to the city once called Nineveh, where Jonah the prophet had preached.

Accompanied by a journalist friend, and my friend, translator and guide, Yohanna, who had been a university professor in Mosul until ISIS drove the entire Christian community out in 2014, we were being guarded by an Iraqi police commander, known only as “the General.” A benignly sinister figure, with jet-black dyed hair and moustache which, on another visit, had managed to turn orange, the General, who had probably been an enthusiastic and vigorous interrogator in the old Saddam regime, joked in Arabic most of the journey from Erbil to Mosul, and filled the car with smoke from the ever-present cigarette hanging from his lips.

As we approached the bridge, I asked the General if he had a gun. He happily removed it from his belt under his shiny jacket and waved it around the car to show us. “Mosul very good, yes,” he asked as we drove through the streets, with destroyed buildings everywhere and cars, pockmarked with bullet holes, roughly pushed to the side of the road. Mosul was not really “very good.” Taken to the old city, we stopped at one of the first of many damaged churches—in fact, the Church where the Chaldean Patriarch, Cardinal Louis Sako, had been stationed as a young priest. ISIS had used most of the churches in the old city either as torture centres, prisons, or places for target practice.

As became a common sight, all Christian symbols, either crosses or statues, had been defaced, shot at, or, in many instances, burned. Leaning over, I saw a broken statue of the Virgin Mary, and picked up a small piece of her broken image and put it in my pocket.

The General told us to follow directly behind him as we walked down the narrow side streets towards the area where the majority of churches were clustered. With most of the buildings not yet cleared of IEDs and coalition bombs, veering from the path would have been very unwise.

“That’s human hair,” said my journalist friend, as we moved through various buildings. I assured him that those strange clumps on the ground were actually bits of carpet. As I entered one darkened room, where the remains of an ISIS fighter had just been removed leaving a rather greasy mess on the floor, I saw that my friend was right. There, on the floor, was a pile of beard hair. Apparently, in the rush to escape and not be recognised, many of the fighters had quickly shaved off their beards; under the Caliphate, the longer the beard, the more devout and dedicated a fighter they obviously were.

Where were the Christians? There were none in the city; no bishops and no priests. It was not ISIS who had begun the mass exodus of Christians from the city in 2014, they merely completed something that was well under way. Following the invasion of Iraq in 2003, and the subsequent chaos, murders and kidnappings, life became increasingly more dangerous for the community in Mosul, with both clergy and laity being targeted for death. In fact, by 2014, there were only a small number of Christians in the city—possibly a few thousand. Most moved to the most populous Christian town on the Nineveh Plain, the town of Qaraqosh. However, on the fateful night of August 6, 2014, the ten year anniversary being commemorated this week, ISIS fighters swept across the Plain, attacking Qaraqosh and other villages, forcing some 120,000 Christians, who had lived on the plain of Nineveh since the time of the apostles, to flee with barely the clothes they were wearing, to the relative safety of Iraqi Kurdistan.

Seeing the altars of these churches used for target practice, and a noose hanging from the bell tower of another, was a very powerful riposte to those who said at the time, and still do, that this had nothing to do with religion, or was a corruption of faith. It was raw, visceral hatred for the doctrine of Christianity, and in particular for the image of the cross. An early issue of one of the glossy magazines that the PR department of ISIS produced (yes, they had one) had several chapters on “Why we hate you,” and most of the reasons were theological.

The caliphate was destroyed, but the ideology and persecution has continued unabated across the Middle East, Africa, and even in Europe.

The year before that first visit to Mosul, I had been close to the city, in the town of Karamles, close enough to hear the coalition bombs dropping on the Old City. Karamles had also just been liberated from ISIS occupation, with many buildings still booby trapped, including the priest’s rectory. Entering the Church, burned out and also used for target practice, the priest took us out to the graveyard where ISIS had dug up the bodies of the Christians and thrown them away. This was not just mindless hatred—it had a purpose—the eradication of memory. The Islamic State wanted to pretend that Christians had never been there, despite their presence since the time of Christ’s apostles.

Ten years later, the Christian community in Iraq, although not being persecuted to the point of death at the moment, is decimated. From more than 1.5 million Christians before the invasion in 2003, there are probably fewer than 100,000 Christians in Iraq. When I was last there, I was told that the Church was working on a number of 50,000 Christians becoming the stable number. An Iraqi bishop described to me, what he called a “silent persecution” of Christians, with their status as second-class citizens undermining all aspects of their lives. Added to that, demographic pressure in Nineveh by Shia militia groups controlled by Iran buying property, affecting local government and, in many instances, trying to close Christian businesses, has made life after ISIS, at least on the ancient Nineveh Plain, a great struggle. The current instability and fear caused by the war in Israel, and Iran’s powerful influence in Iraq, makes those who were hoping for a better future, increasingly fearful.

However, there are small seeds of hope. The majority of those Christians who felt the need to leave have already left. Some are even returning, if there are economic incentives. Charities, such as my own—Nasarean.org—which mini micro-finances small family businesses, are helping Christians stay, start a small family business, and build a future for their children. It is the answer to migration and to the lie of ISIS that Christians were never there. Rather than encourage migration, although Christians were never among the large numbers of those allowed to migrate to either the United States or the U.K., governments ought to be supporting organisations which help the communities stay in their own lands.

Finally, at the end of that first visit to Mosul, we arrived at the ruins of the Great Mosque, where Abu al Baghdadi proclaimed the caliphate. Rather like the “thousand year Reich,” it reminded me of Hitler’s bunker in Berlin, the only difference being the Islamic State is powerfully resurgent, especially in Africa.

Surveying the scene, I asked the General what he thought would happen to the ISIS fighters who returned to Europe. Laughing, he said they would receive jobs and a new house, and then start there what they had done here. Then he lit another cigarette.