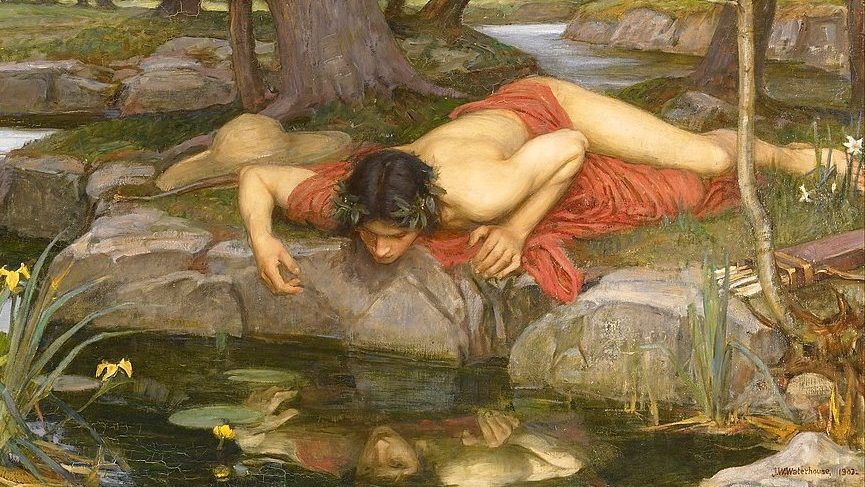

The detail from “Echo and Narcissus” (1903), a 109.2 × 189.2 cm oil on canvas by John William Waterhouse (1849-1917), located in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

The mark of an accomplished intellectual is the ability to formulate some idea or concept that sheds light on a whole constellation of issues, bringing coherence and clarity to something that one might previously have grasped in only a partial and disconnected manner. One such concept is the “entrepreneur of the self,” as formulated by the Korean-born German philosopher, Byung-Chul Han.

Han is proving to be one of the most trenchant and devastating postmodern critics of neoliberalism alive. He deploys the concept of “entrepreneur of the self” in several works where his main critique of neoliberalism is laid out in succinct but comprehensive fashion, e.g. The Burnout Society, Psychopolitics, Topology of Violence, The Agony of Eros, and others. The concept is unique in its ability to explain a whole panorama of social and moral issues that define contemporary society.

In brief: under neoliberalism, we no longer perceive a rigid class division between the exploiter and the exploited. Rather, we are all simultaneously the exploiters and the exploited, for we exploit ourselves, making a life of pure labor the source of our happiness, our self-esteem. Labor is no longer something we perform out of necessity or external compulsion: it is an act of self-determination, an act of freedom. Han writes in The Burnout Society, “Twenty-first-century society is no longer a disciplinary society, but rather an achievement society. Also, its inhabitants are no longer ‘obedience-subjects’ but ‘achievement-subjects.’ They are entrepreneurs of themselves.” Consumption too plays into this dynamic of self-imposed self-production, the achievement of experiences or the creation of an ego-identity. We are capitalist, laborer, and commodity, all wrapped into one—entrepreneurs of ourselves—and because of this we think ourselves free.

As an entrepreneur of the self, the neoliberal subject is concerned with maximizing his or her own functionality within a system of self-exploitation. This is the function served by the variety of self-help programs offered in the realm of psychology, as well as the various modes of physical optimization offered in the culture of fitness. In Han’s analysis, both men and women are subject to this regime of relentless self-optimization, which has no other function than to augment their functioning within the system. Heightened performance is the maxim that drives contemporary society’s obsession with both physical and mental health.

Consequently, the self-entrepreneur is a narcissist who looks upon the world as nothing but a collection of objects for consumption, instruments of the narcissist’s own self-creation and performance maximization. As such, “the world appears only as adumbrations of the narcissist’s self,” as Han writes in The Agony of Eros. What earlier theorists like Adorno and Marcuse identified as the “instrumental rationality” of the bourgeoisie now belongs to everybody: the whole world is instrumentalized for the purposes of the ego and its self-production. Whatever gets in the way of the subject’s maximum performance and achievement is discarded as irrelevant by the ruthless calculation of instrumental reason.

This concept is powerful because it explains so many puzzling things about contemporary society, even beyond the phenomena that Han himself uses it to explain. For example, it is difficult to avoid the obvious implications which this analysis has for phenomena such as identity politics. The identitarianism of late neoliberal “woke” ideology is nothing but the entrepreneurialism of capitalism itself, transferred into the domain of psychology—and extended to all the inhabitants of present-day capitalism. Every person is an entrepreneur of his own identity, and he compels himself to labor incessantly in the service of his entrepreneurial ambitions. This affects everybody regardless of gender differences and explains the rise of feminist and LGBTQ ideology, which proceed under the assumption that one can be whatever one wants to be. Likewise, it affects not only the wealthy and the privileged, but even (in our own day) those who are less privileged, but still imagine themselves through the cultural lens of achievement society.

In Topology of Violence, Han explains:

men as well as women undergo cosmetic operations today in order to remain competitive on the market. The compulsion to optimize the body encompasses everyone, indiscriminately. It doesn’t just produce Botox, silicone, and beauty zombies but also muscle, anabolic steroids, and fitness zombies. As a doping society, the society of achievement knows no class or gender differences. ‘Top dogs’ are affected by the demand for performance and optimization just as ‘underdogs’ are.

The panorama of cosmetic operations that Han is describing almost certainly include those involved in sex-change, whose logic follows the gender-indifferent demands of a society predicated on self-production and performance, regardless of gender. Similarly, “doping” as a tool of a performance enhancement characterizes both the wealthy and the poor, who both indulge in a variety of drugs and enhancers as a kind of substitute for therapeutic self-optimization. In Marxist terms, these operations serve the purpose of enhancing the worker’s labor power—only the worker in this instance is auto-exploited, rather than exploited by another.

Another potent example that Han himself uses in The Agony of Eros is that of pornography, which he perceives as a narcissistic abuse of sex, and thus the opposite of eros rightly understood. Eros is only possible through a kind of total emptying of the self into the Other. But in a pornographic society, the Other is no longer even perceived as other, but only as an object on display—a commodity—to be used for the ego’s own self-expansion and self-gratification. He writes, “Capitalism is aggravating the pornographication of society by making everything a commodity and putting it on display” In such a society, the Other as such has disappeared and been subsumed into the ego’s drive for consumption, performance, achievement, and self-production.

Pornography is just one example of how the neoliberal subject looks upon others as instruments of its own self-creation. In general, this is how we think in many social contexts: other people are mere instruments to be used, capital to be invested in our own self-creating entrepreneurial endeavors. Alternatively, they are consumers to whom we market ourselves as commodities—not simply as we might market our labor-power to a capitalist; rather, our very identity, our image, our brand, is the commodity we sell and display for the viewing of others—think social media: “In social networks, the function of ‘friends’ is primarily to heighten narcissism by granting attention, as consumers, to the ego exhibited as commodity,” Han writes in The Burnout Society. Or again, other people are waste products, to be discarded like trash when they are no longer useful for our own self-creation or self-aggrandizement. To put the same thing differently, our relations to others are merely contractual and transactional, contingent upon their usefulness to our own self-interest. No relationships are seen to require enduring commitment, and no person is seen as an Other deserving our unconditional love and reverence.

But Han’s analysis also encompasses some issues that he himself does not touch directly. One example that comes to mind is that of abortion. While nowhere addressed directly by Byung-Chul Han (to my knowledge), nonetheless it fits perfectly within the frame of his analysis. Abortion is an accommodation to the entrepreneurial ambitions of women in particular, who no less than men are encouraged to participate in the contest for self-creation and maximum achievement. The pursuit of maximum achievement requires a hyper-active way of life that leaves no room for the enduring commitment that accompanies motherhood. Likewise, it requires a fixation on the self that leaves no room for the self-emptying love that is demanded by the presence of another person, particularly one’s own child. (It should be noted that abortion is also convenient in this way, though perhaps less directly, for men who would rather pursue achievement and success than commit to the responsibilities of fatherhood.)

The logic that informs abortion is exactly that of the “entrepreneur of the self,” for whom other people (as well as oneself) are just objects to be manipulated, consumed, and discarded, according as they are useful or lose their utility for one’s entrepreneurial project of self-creation. Rather than an Other to be contemplated, loved, and revered as a person who is ineffably beautiful, divine, and awe-inspiring, the unborn child is seen as a mere waste product. Rather than something that demands one’s own total self-giving and self-abnegating love, the child is seen as a mere inconvenience, an obstacle to the ego’s project of self-production. Therefore, the child becomes a victim of the ego’s entrepreneurial drive for creative destruction.

Like the cosmetic procedures which the “achievement-subject” undergoes to enhance performance, abortion serves the purpose of maximizing the woman’s labor power. As always, accumulated labor power always translates into accumulated capital as well, but in the case of self-entrepreneurship and self-exploitation, they are experienced as one and the same by a single subject: the neoliberal “achievement-subject.” The violence of abortion directly serves this accumulation of labor power, this feeling of growth or capital accumulation. As Byung-Chul Han writes in Capitalism and the Death Drive, “The economy of violence is ruled by a logic of accumulation. The more violence you exert, the more powerful you feel. Accumulated killing power produces a feeling of growth, force, power—of invulnerability and immortality. The narcissistic enjoyment human beings take in sadistic violence is based on just this increase in power.”

Only a society of narcissists, concerned only with the endless accumulation of their own egos, would treat both the born and unborn as objects to be manipulated, consumed, and discarded in the process of ego-production. The protection of life and of love requires a fundamental shift away from the project of self-entrepreneurship that Byung-Chul Han identifies as central to neoliberal capitalism. It requires a new realization of the significance of self-emptying and self-negation, the prerequisites to a true encounter with the Other as other—the only encounter that can truly make life meaningful.