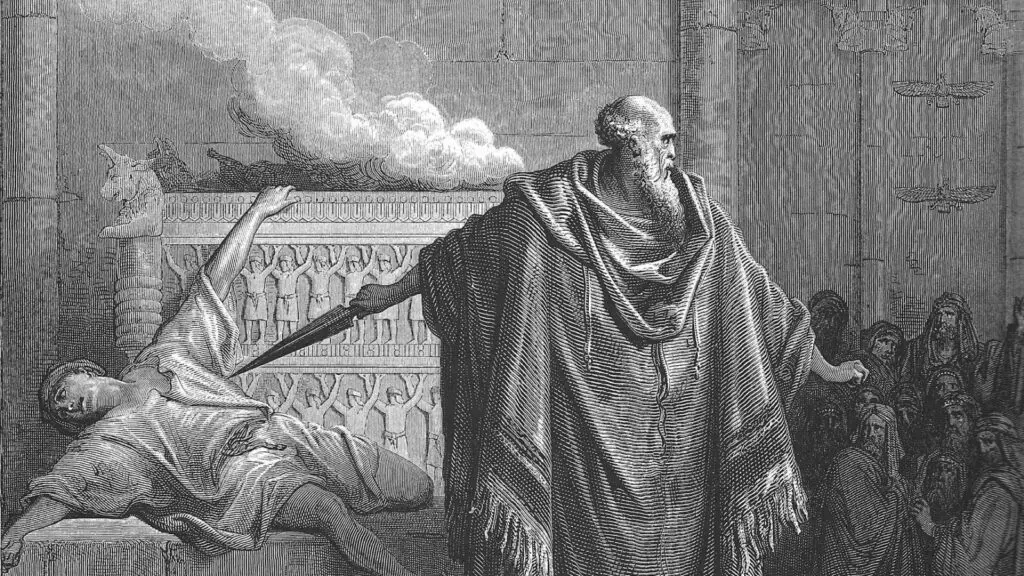

Mattathias and the Apostate (c. 1866), a drawing by Gustave Dore (1832-1883)

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

This essay is an abridged version of remarks given by Fr. Benedict Kiely at the National Conservatism Conference in Brussels on April 17, 2024.

Preparing for this talk, the news came in that, by a large majority, the members of the European Parliament had voted to have the so-called ‘right to abortion’ in the European Union’s Charter of Fundamental Rights. A prophet, Monsignor Knox once wrote, sees the “evils of the day with a clear eye.” To call the right to murder our unborn a “fundamental right” is evil, and any country or continent that enshrines such a right will not survive. God is not only a God of mercy but also a God of justice. Shame on the members who voted for this; there will be a reckoning.

The title of this panel is called ‘Faith and Family in Crisis,’ and who can deny it? The wilfully blind, the ignorant, or those who both wish for the crisis and are actively encouraging it. I do not intend to give an endless list of examples of what has been happening over the last 100 years or so to cause this crisis, which is accelerating rapidly. If I address certain issues, it is to challenge us all who call ourselves conservatives, but most especially the Christians among us, to fight the good fight with all our might. It is also getting more difficult to attempt to give a positive vision for us to work on and not be drowned in the slough of despondency and discouragement.

We know, in the Bible, that apart from being a moment of destruction or calamity, the word ‘crisis’ can also mean a moment of opportunity. Etymologically, the word comes from the Greek root meaning “turning point in a disease”—it can either get much worse or much better. Later, it developed into the word for a ‘moment of decision.’ The patients, both faith and family, are very sick; they are, in fact, inseparable in their sickness. When the faith is sick, inevitably the family suffers, and vice versa.

Interwoven as they are, let us first glance at the sick patient called the family, examine some of the signs of the condition it is suffering from, and propose some life-saving medication that will bring the patient out of this moment of crisis. We must, of course, in all these proposals, have the true conservative virtue of humility, acknowledging that time, when properly managed, can truly be the great healer. A conservative and a Catholic knows that nothing good happens quickly, especially when rebuilding a virtually destroyed Christian culture. I often think, when surveying the West, of what St. Augustine must have felt sitting in his diocese of Hippo, in present-day Algeria, seeing the barbarians destroy all that appeared civilised. In a less elevated vision, I remember the scene in The Planet of the Apes—the good old Charlton Heston version—where, right at the end, the ruins of 20th-century America appear buried under the sand, and Heston almost despairs—we are, in some way, both St. Augustine and Charlton Heston, with work to be done, in faith and hope.

Chesterton, the apostle of common sense and a worthy patron for all our endeavours, called the family the “one anarchist institution.” He said it is anarchist because it “is older than the law, and stands outside the state.” The family, as those of us who believe in its divine origin know, comes from the direct work of God’s creation—“male and female, He created them,” created in His image. All that violates the family—law, state, culture—ultimately violates both the will of God and the intrinsic (although perhaps not infinite) dignity of the human person made in God’s image and redeemed and given even greater dignity in the Person of Jesus Christ.

Again, Chesterton said that “the truth is that only men to whom the family is sacred will ever have a standard or a status by which to criticise the State.” This is very important, and our first positive proposal—or re-proposal is that the family is sacred. Without listing all the ways we know that the patient known as ‘family’ is in crisis, it is, first and foremost, from those who do not believe in its divine origin, who therefore do not see it as sacred, and who are determined to manipulate it, for either naïve but false, altruistic ends, or far darker ends.

The ”totalitarian state—and perhaps the modern state in general—is not satisfied with passive obedience; it demands full cooperation from the cradle to the grave.” Not my words, but those of the great Catholic historian, Christoper Dawson, written many years ago. How prescient, how prophetic. He had, of course, the horrors of Nazism and Communism in mind, but he was indeed prescient when he spoke of the “modern state in general.” We know the increasing influence of the state over every area of family life, from cradle to grave. Not that there is no place for law or the state, but it must be severely limited, and the present overreach be reversed. “If individuals have any hope of protecting their freedom, they must protect their family life”—the wisdom of Gilbert again. We, conservatives, must be at the forefront to defend what is strangely called the ‘traditional family.’ There is a place for the state—governmental support for marriage and children, for example, as in Hungary—but there must be a vigorous defence of the sacredness of the family, and the spirit of defeat needs to be resisted.

This leads into the second area where we can fight back, defend the family, and resist the forces determined to create something very different. Once again, Dawson wrote something so profound, so true, and so obvious—yet often so neglected by the Church and those who claim to defend the family: “Universal secular education is an infallible instrument for the secularisation of culture.” The communists knew this; anyone with a brain knows this. We see the evidence of this all around us. It is a sign of the sickness of the patient. It is deliberate, intentional, and very successful. Christian, classical education is the antidote, and huge resources, especially from the Church but also from concerned citizens, must be directed to this cause. Parents have the right to educate their children; parents have the right to resist the indoctrination of their children; parents, even with state support, have the right to send their children to schools of their choice; or, and this is very important in Europe as the state continues to seek to eliminate this right, parents have the right to home school their children.

Closely linked with education, but also part of the intersection of the crisis of both faith and family, is culture. We know the etymology of that word. Dawson writes that the “challenge of secularism must be met at the cultural level, if it [is] to be met at all … otherwise Christians will be pushed, not only out of modern culture, but out of physical existence.” Welcome to the West. Here I challenge the Church.

Dawson writes:

Now the Christian world of the past was exceptionally well provided with ways of access to spiritual realities. Christian culture was essentially a sacramental culture which embodied religious truth in visible and palpable forms—art and architecture, music and poetry and drama, philosophy and history were all used as channels for the communication of religious truth. Today these channels have been closed by unbelief or choked by ignorance.

Obviously, this is primarily and principally the work of the laity, but the encouragement and commitment of the clerical caste, and particularly the hierarchy, is essential. The redemption, or recapturing of culture, is the work of beauty, truth, and goodness. This is not dilettantism or aestheticism; it is part of the cure for the crisis of faith and family. I managed to get through six years in the seminary without taking one course on art, music, sacred architecture, or indeed culture. I suffered two semesters on Gaudium et spes, torture worse than being flayed alive with a blunt knife. We need clerics who care more about Gaudí than golf and who fervently believe in and promote beauty in all its forms in the Church. Dawson says that because the culture is now post-Christian, we have what he calls a “double task”: to recover our own cultural inheritance and to communicate it to a “sub-religious or neo-pagan world.” That recovery is most certainly part of the work of the institutional Church; it is positive and exciting, and it must be seen to be of critical importance.

Similarly, the communication of that classical Christian culture is the work of the Church, one of the reasons St. John Paul II wrote his beautiful letter to artists. It is, as said, principally the work of the laity, supported by the Church. It is being done, and, I have to say, much better in the United States than in Europe. It costs money, and we cannot penny-pinch with the restoration of Christian culture. I was just in Florida visiting a parish that had just built a beautiful, and indeed, very expensive, new church. Beauty is a far more evangelical tool than PowerPoint presentations or parish programs. Dawson says that the second task—that communication of our restored cultural inheritance—is not as difficult as we think because, he says, “people are becoming more and more aware that something is lacking in their culture.”

This echoes the words of Walker Percy, who said that at some point, young people would be so sick of the culture around them that they would come to the Church. We better have something for them, and part of the crisis of the Faith is the failure to see that in the liturgy, ancient and modern, beauty must captivate before it converts. Benedict XVI wrote that “Christians must not be too easily satisfied. They must make the Church into a place where beauty—and hence truth—is at home. Without this, the world will become the first circle of Hell.” To the extent that beauty, and hence truth, is not at home in the Church, the Faith is in crisis.

We now turn to the final area where the sickness of faith and family coalesce and where, perhaps, the crisis, the moment of recovery or destruction, is most acute—the very meaning of what it means to be human.

Six years ago, in a book review in First Things magazine, the Cambridge theologian Richard Rex gave us the perfect reason why we are discussing this issue today. Rex said, correctly, that, so far, in the life of the Church and hence Christianity, there have been three crises—moments when things could have gone very badly. The first crisis, dealt with over a couple of centuries, was the question of ‘What, or who is God?’ answered by the Oecumenical Councils, particularly Nicaea and Chalcedon. The second crisis, brought on by the catastrophe otherwise known as the Reformation, was the question, ‘What is the Church?’ Rex wrote that we are now living in the third great crisis in the life of Christianity—‘What is man?’ This, sadly but appropriately for our discussion, is not a crisis that we can afford to wait centuries to cure; the survival of the human race depends upon it.

Benedict XVI wrote that the modern state in the West, with its “radical manipulation of man and distortion of the sexes through gender ideology … opposes Christianity in a particular way.” Rex writes that on a whole host of issues—abortion, IVF, euthanasia, to say nothing of human sexuality—Western society is “moving in a very different direction from Catholicism …. the new moral consensus,” he says, is “utterly irreconcilable with Catholicism.” This is indeed a crisis of faith and family, and it is extremely serious. Why? Benedict says that modernity, which is independent of the truth, “makes man his own creator and disputes the original gift of creation … and manifests a will to recreate the world contrary to its truth.” This will, he says, “necessarily lead to intolerance.”

That, I might say, is a rather gentle way of putting it. It will, and has already, led to cancellation, the loss of employment, imprisonment, and, perhaps on the horizon, worse. Christians, who uphold basic doctrine on human creation, the distinction of the sexes, and the right to life from conception until natural death, are already the equivalent of dhimmis in the Muslim world. Rex calls them “subaltern groups,” who, he says, “learn their position in society.” How many Christian doctors, nurses, and teachers are now in those “subaltern groups?” Know your place, go with the flow, do not speak, and, above all, do not bring your faith into the public square. This crisis calls for the Church to be robust in the defence of God’s plan for humanity, but it is the very essence of this demonic corruption of the human person and their calling as children of God that demands we be more active.

Rex reminds us that the “duties of conscience apply just as much to our relationship with the Church as with the State … if they need to be reminded of the truths that have been entrusted to them,” he says, then “it is our duty to remind them.” In a time of confusion, as Michael O’Brien wrote many years ago, we need clarity from the Church. Despite the recent document, which Babylon Bee amusingly headlined “Breaking news … Church teaches Catholic doctrine.” This crisis needs robust, vigorous, joyful preaching and teaching. This is a message of hope for a lonely and confused culture. The Church that marries the spirit of the age, as Dean Inge said, will be a widow in the next one. But also the Church must not flirt with the spirit of the age, engage in a dalliance with the spirit of the age, or the Church will be cuckolded and the spirit will not be faithful.

Not long before he died, Pope Emeritus Benedict wrote something extraordinary. Looking at the story in the Old Testament of the Maccabees, those faithful Jews who refused to deny their identity and their fidelity to the God of their ancestors, Benedict points to the figure of Mattathias, who prefers to die rather than obey falsehood. Benedict writes, and these are, I think, stunning words: “The attitude of Mattathias (who said) ‘we will not obey the king’s words’—is that of Christians.” In brackets, he wrote next to “not obeying the king’s words,” “modern legislation.”

We are now in apostolic times. The Faith and faithful families changed the culture and created Christian civilisation in the past. The Faith, witnessed by fervent preaching and living, told men and women, the poor, the downtrodden, prostitutes, and slaves, that they were sons and daughters of God. Families lived that faith, changing a culture of death to a culture of life. They were a creative minority with a message of hope. God, wrote Cardinal Mueller, is the “origin and goal of human beings. He Himself is the goal of our infinite quest for truth and happiness. Forgetting God, we miss our true being.” Preaching and living that makes this crisis an opportunity.