The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

It would be implausible to claim that we can learn everything we need to know about the moral status of a political movement from an acquaintance with its aesthetic groove. However sumptuous certain people may find the chiselled sculptures of Arno Breker or the energetic oil paintings of Jacques-Louis David, to meet someone with a high opinion of either man’s artistry is still one step removed from having rumbled a Nazi or a Jacobin. Rather more than a soft spot for the signature styles of these ideologies was required, not least by the fervent ideologues themselves, for full-on membership of the tribe.

Yet it would be equally foolish to argue that morality and style are wholly independent of one another. Their connection is not logically ironclad. Nevertheless, if we define a man’s ‘political outlook’ as a vision of what he believes to be both possible and desirable on this side of heaven, then the moral content of that vision and its aesthetic presentation are bound to overlap. For the most part, ideological conviction exercises a negative effect: it will discipline the artist under its spell with commandments about what not to do rather than bother him with an interminable list of positive instructions. Thus, while the Nazi painter is not forced to indulge in depictions of slaughtered Untermensch, he is certainly forbidden by his creed from painting, say, Jews or Slavs in a sympathetic light, still less an elevated or heroic one.

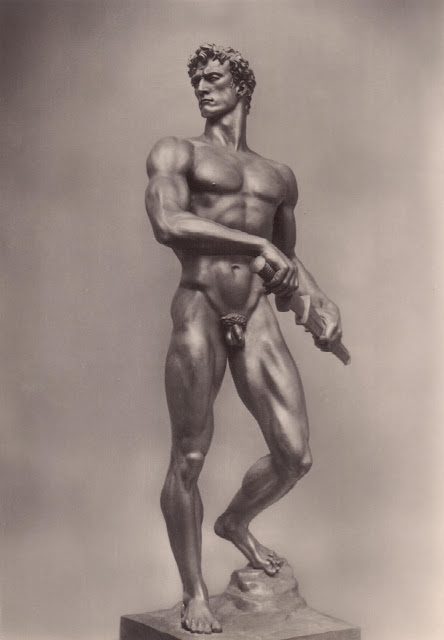

But despite these tedious caveats about the relationship between art and morality, it is rare for even the most loathsome political creed to have no redeeming aesthetic features. Wokeism—that ghastly, ill-defined hybrid of our time—is making a compelling bid to be the first such ideology to win this accolade. Above, I trust readers will agree, is a typical, instantly recognisable example of the woke aesthetic that saturates so much of our public life.

All totalitarian art runs the risk of kitsch. This is because sentimentality is not so much what happens when feelings are “put in the driving seat,” as one philosopher puts it, but when they are made a slave to theatre. Kitsch is therefore incompatible with true feeling, which cannot endure such bondage without dying. And since both the Soviet vision of a classless paradise and the Nazi dream of a racially purified Volksgemeinschaft were either unattainable or attainable only by the most gruesome means, art under both systems had to be conscripted into maintaining the illusion—the false and, over time, one imagines increasingly feigned feeling—that a kind of earthly salvation was being won for the inhabitants of these anti-human hellscapes. If sentimentality is the exhibition of feeling with both eyes on the nearest mirror and none on the feeling itself, the totalitarian experiments of the last century took this self-involved relationship to artistic expression to its most garish extremes.

Still, at least the Soviet aesthetic boasted a triumphant, futuristic starkness, lauding the dignity of labour and the heroism of a society devoted—officially at least—to reclaiming that essential gift. In a similar way, Nazis like Breker paid a spirited homage, albeit with inevitable eugenic caveats, to the potential excellence of the human form.

The woke style of the moment, by contrast, is irredeemably blobby, a saccharine antidote to striving and aspiration, a mawkish tribute to an imagined future in which ugliness and mediocrity slouch supreme.

Nothing can be privileged, so nothing is foregrounded, extolled, or marked out for special attention. Sharply defined breaks in the general pattern or bursts of chiaroscuro lighting might engage the human eye, but at the mortal expense of the basic levelling message: sameness is safest. And in any case, even to think about pursuing beauty, as if that term is unproblematic, would be to inflict violence upon those who suffer from our society’s exclusive, maliciously constructed beauty standards. Likewise, to inject drama into the scene would be to complicate the simple-minded idealism that prevented the content creator (I cannot bring myself to say artist) from producing anything other than a still, vitality-sapping paean to uniformity. Only the colours are permitted variety—for obvious reasons, given the incurable obsession with racial diversity and lurid rainbow flags. Beneath this superficial chromaticism, however, the stuff itself is fundamentally grey in spirit and submerged in a doughy form.

Lack of ambition is a uniquely embarrassing flaw in a utopian. The Nazis and the Soviets could never be accused of it. This is the basic insight behind A.J.P. Taylor’s ingenious comment that, throughout the 20th century, idealists killed many more people than cynics did. Ideological determination is more deadly than even the most unscrupulous Realpolitik. However, one gets the sense from the distinctive woke manner that the activists who revel in it would sooner neuter and extinguish every vestige of excellence in men and women than go to the trouble of killing them. But while making a squishy protest against the ‘inequities’ that result from honouring achievement, the aesthetic manages at the same time to be smugly utopian, with its garishly unnatural colours and its vision of a society in which blood, sweat, and tears have been made obsolete. In a way, of course, there are few things more ambitious than striving for a world so inoffensively ordered that there is no longer any need for ambition at all. The irony is that, in seeking to be inoffensive and unthreatening, the wokesters succeed only in the most pyrrhic fashion, because they necessarily offend the rest of us who understand that denouncing high standards as offensive is itself an offence against human excellence, rather as indulging child-like fantasies of a world without danger is the real threat to any society intent on survival.

Finally, the wokesters’ belief in the social construction of all values means that, in any imaginative protest against what we have created, they are committed to depicting a world in which what we instinctively consider ugly or deformed, such as a bearded woman or an ungodly muffin top, come to be seen in a pristine, post-revolutionary light. Precisely because they regard natural human desires, standards, and tendencies as socially constructed assaults on what could pass for beauty if only we put our minds to deconstructing what ‘beautiful’ means, they are forced to sell the apex of alienation—that which is maximally remote from our nature—as a paradise-in-waiting. At its best, when fantasy is an artist’s favoured mode of expression, the result is J.R.R. Tolkien. But woke fantasy, despite its preposterous conceit in thinking of itself, unlike Lord of the Rings, as an earnest social blueprint rather than a symbolic flight of fancy, is criminally pedestrian: it conjures up a vacuous, surreal, candy-floss dreamworld in which the most spirited aspects of human nature have been surgically removed. The resulting husk is then served up to us as liberation. The dissidents of this future society, if it is seriously tried, may not die in gulags or extermination camps. It seems more likely that we will all succumb to a lethal tedium caused by the combination of compulsory faux-wisdom and a consequent crisis of meaning that spares nobody.

In short, the woke aesthetic represents the shaming of the men who built civilisation and the women who nurtured it by a minority of tenth-rate leeches whose indulgent habits and luxury beliefs would be not only deadly but unthinkable without the sacrifice of their betters.