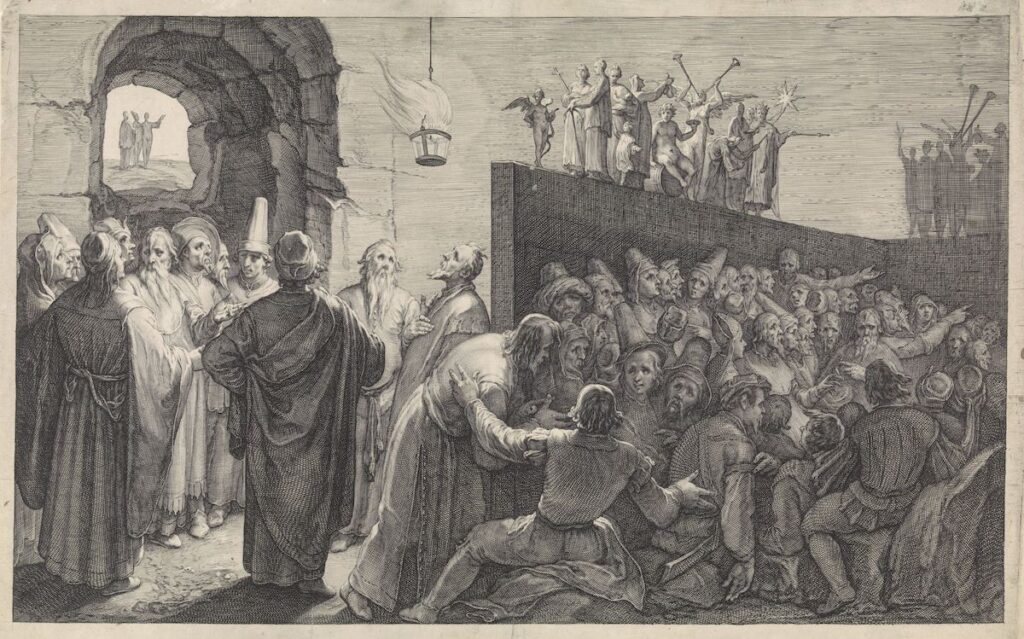

“Grot van Plato” (Antrum Platonicum) (1604), a 16.3 x 26 cm engraving (possibly) by Joseph Mulder (1658-1742), after Jan Saenredam, after Cornelis Cornelisz, located in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

The most famous image in the history of philosophy occurs in Plato’s Republic. Socrates introduces it by saying that it concerns our nature in its education and lack of education. Man is likened to a prisoner in a cave who, because he is enchained, cannot move his head or body away from the wall of the cave, upon which shadows are cast against the light of a fire burning behind the prisoners. A priestly class moves in front of the fire with a procession of objects whose shadows the sorry prisoners regard as the things themselves. If a liberator could free someone from this situation and drag him towards the fire, most slaves would prefer to run back down to the shadows to which they have been accustomed. Supposing anyone could complete his liberation, leave the cave, and look directly at the sun—which, at this point in Plato’s allegory, symbolizes an intellectual act of understanding, not a physical act of seeing—he would need to be compelled to return to the cave: that’s how preferable the higher, contemplative state is to our natural oblivion. If he does return, he is likely to be killed by the prisoners, who want nothing less than to have their comfortable, customary ignorance questioned.

The broader context of the image, its place in Plato’s Republic, concerns the question of whether justice is good in itself or good only for its external rewards. Socrates is asked to make the case that justice is good in itself. He does so over the course of an elaborate argument that culminates in the figure of the philosopher-king: “There will be no rest from ills for the city, nor, I think, for human kind,” unless kings philosophize or philosophers rule. Justice requires the rule of the wise. In order to make any sense of that strange claim, it is necessary first to understand whom Socrates means by the philosophers. It is in answering that question that he introduces his image of the cave. The philosophical state of soul is distinguished from the everyday one just to the extent that it represents a turning around of the soul from what seems to be (the shadows, opinion) towards what truly is, from opinion to knowledge. If that kind of conversion, ascent, and quest for wisdom is possible, a strong case can be made that justice requires the rule of the philosophers, and that it is good in itself. Philosophy helps produce a well-ordered soul, and the well-ordered soul is a natural ruler. (This truncated version of the argument is, of course, unlikely to persuade; for the complete demonstration, the entire Republic is necessary.)

Today, the image of the cave is regarded with suspicion. It seems to call for rule by experts and social engineers, for a tyranny of technocrats: a dubious, if not diabolical, prospect. The masses are interpreted as prisoners subject to the ‘manufactured consensus’ of a class of media high priests gathered around a promethean fire up above. Plato seems to have legitimated the idea that they rule by right of esoteric wisdom. Before too long, it looks almost plausible that high-profile figures in science, technology, and government are a dystopian Platonic illuminati. How can an image as powerful and true as Plato’s original acquire such a sinister aspect and serve no longer as an aspiration towards education but rather as an admonition against rule by experts?

Leo Strauss’s extension of the cave image may help us to answer this question. Strauss provocatively suggested that modern society is in a cave beneath ‘the cave.’ If the cave in Plato’s allegory symbolizes, as Socrates says it does, our nature with respect to its education or lack of education, our natural ignorance and the possibility of overcoming it, then the cave beneath the cave refers to the situation where we have left the natural condition through technical procedures and historical beliefs. These are procedures and beliefs that, for Strauss, do not bring us closer to knowledge of what is, but rather they remove us further from it, exacerbating our slavish condition. If the old solution to the problem of our natural ignorance was to ascend by philosophizing, the modern solution has been to dig our way out through a kind of subterranean inverted ascent, i.e. a descent, perhaps towards the bright light of the earth’s magma core. Contemporary technocratic titanism is therefore so far from Platonic political philosophy that it is practically its opposite. We must try to understand what it means about our situation that we automatically see the Platonic alternative not even through the looking glass but through the black mirror.

Strauss first mentioned his idea of the second cave in a lecture on “The Religious Situation of the Present,” the name of a talk he was invited to give in 1930 (available as an appendix in Reorientation: Leo Strauss in the 1930s, edited by Yaffe and Ruderman). Strauss walks his audience through the title, step-by-step, explaining to them what, in his view, the title actually means to say. He does this so that he can pose the real question more clearly. He argues that to ask about the religious situation of the present doesn’t necessarily mean to ask about religion: rather, it refers to the need for guidance concerning the present situation “in the most important respect,” which is not solely religious, but more broadly intellectual. That’s how Strauss moves from “the religious situation” to “the intellectual situation.” And yet, as he continues, it is not quite right to speak of an intellectual situation: “the intellect is not a thing that is situated.” Strauss’s point here can seem obscure, but he is implicitly referring to an age-old debate about the nature of our reason, our intellect. Is it something ‘in us’ that nevertheless transcends our time and place? Or is it always embedded in the ‘lived experience’ of an historical subject? Strauss favours the former perspective. And he uses it to pivot from the idea of “intellectual situation” to something else. For Strauss, what is characteristic of the intellect is not its situation, but its action, and the main action of the intellect is to question. So we are faced with the issue, not of the religious situation of the present (like in the title of the talk), but rather of the intellectual question of the present or, more simply, the question of the present. In this way, Strauss redefines and refocuses the original theme.

But why the present? At first, it seems obvious: we are here, in the present, and we want to know what concerns us precisely here, and not somewhere “once upon a time, in a land far away.” And yet, as Strauss observes, if you could imagine yourself back in time somewhere else asking a wise man of the 12th century how to free yourself from perplexity and confusion, he would respond by talking about substantive questions, like “creation, providence, the unity of reason and revelation,” questions that are relevant to any present because they are serious questions for all time.

Nothing is more relevant to the present than what is perennially important—questions, Strauss says, like: “What is the right life? How should I live? What matters? What is needful?” Strauss continues: “Thus, our modern topic of the ‘religious situation of the present’ boils down to the old, eternal question, the primordial question.” To speak merely about the situation of the present without raising the primordial question of the right life is, for Strauss, akin to “doing nothing other than the cave dwellers who describe the interior of their cave.”

And yet, we cannot just raise the old, eternal question. Because we are in a cave beneath the cave, we must ascend to natural ignorance first, which is the starting point of philosophizing in Plato. But, according to Strauss, to do this requires “the greatest effort.” It requires that we work against the forces of inertia and gravity, that we are not lured by the delusions of progress, digging ever more deeply into our cavernous, unnatural future.

There is not one way to interpret the cave beneath the cave. In his formulation, Strauss refers to a passage in Maimonides that suggests that biblical revelation has made ascent more difficult, because through biblical revelation we inherit a tradition and come to rely on that tradition—and not on questioning—for guidance. Strauss’s view was that Maimonides’s insight applies to all traditions based on revelation, not only Judaism: revelation as such, and in particular as the source of a religious tradition, is essentially incompatible with philosophy, with the sovereign intellectual activity of questioning. The Enlightenment thinkers had attacked religious belief under the banner of a war on prejudice, but they wanted to replace it with a new kind of scientific knowledge; only Nietzsche, who also attacked the prejudice in favour of science, carried the project through radically enough to make possible a return to old-fashioned natural ignorance, Strauss argues. (Not everyone will share Strauss’s judgment about what Nietzsche accomplished, but Strauss—who famously admitted to being “dominated and charmed” by Nietzsche from age 22 to thirty—was, as Laurence Lampert has argued, one of the most astute and understanding readers of Nietzsche in the 20th century, so we should give some consideration to his account of Nietzsche’s significance.) In 1930, Strauss wrote:

The tradition has been shaken at its roots by Nietzsche. It has altogether forfeited its self- evidence. We stand in the world completely without authority, completely without orientation. Only now has the question [how to live] regained its full sharpness. We can again pose it. We have the possibility of posing it in full seriousness. We can no longer read Plato’s dialogues superficially, in order to notice admiringly that old Plato already knew this and that; we can no longer polemicize against him superficially. And the same with the Bible: we no longer think without evidence that the prophets were in the right; we ask ourselves seriously whether it was not the kings who were in the right. We really must begin entirely from the beginning.

Nietzsche, then, has made it possible for us to begin again, not with any doctrine or dogma, but—and this is the most important thing for Strauss—with basic questions, foremost among which is the question of what is right. That we can still pose this question is evidence that we, in Strauss’ account, “are still in a certain way natural beings” and not yet thoroughly “antinatural, perverse.” “The need to know, and therefore the questioning, is the best guarantee that we are still natural beings, humans—but that we are not capable of questioning is the clear symptom of our being threatened in our humanity in a way that humans have never been threatened.”

As Allan Bloom wrote in Giants and Dwarfs: Essays, 1960 – 1990, summarizing an old argument: “There are two threats to reason, the opinion that one knows the truth about the most important things and the opinion that there is no truth about them. Both of these opinions are fatal to philosophy; the first asserts that the quest for truth is unnecessary, while the second asserts that it is impossible.” Both threats close the door to the kind of questioning that Strauss suggests is the last preserve of our naturalness, our humanity. Philosophy is possible and necessary. Neither nihilism nor dogmatism is inevitable.

Why did Strauss believe we are less capable of questioning? It has to do with the second cave. Our technological society, which believes it solved the problem of our natural ignorance by digging down into an artificial world, is conditioned by a kind of historicism, the belief that all principles of living are historically conditioned, so that there is nothing we could learn from, for instance, dead Europeans, any more than we could hope to revive the institution of the duel or the ball. Principles change along with historical periods. It was that opinion about truth and time, reflected by exaggerated interest in “the present,” that Strauss challenged. If we have started to solve problems technologically and believe, implicitly or explicitly, that all problems have solutions, and, finally, if we think we, living in the modern technological, historical era, are the first to have understood how all these things hang together, then it follows that “we stand at a higher stage of reflection than earlier human beings: we regard ourselves as having progressed.” Under this belief, it goes without saying that we know more than Plato could have known because he lived then and we live now and make use of all progress that has happened in the meantime. This belief that we know more obstructs basic questioning:

[W]e are more incapable of questioning than the earlier generations—since we know more, since we know too much. But we are compelled to question since, at bottom, we know nothing. Being fundamentally ignorant we cannot come to knowledge since we know too much. Since we believe we know too much. We will not be able to remove our radical ignorance until this belief that we know is abolished.

It was the Enlightenment belief in progress that closed off the fundamental questions through the presumption that science is the basis of all the relevant answers. History, in the Enlightenment view, is progressive: it has progressed to this fundamental insight about science and prejudice. Therefore the old questions are closed: they could not have been posed correctly without understanding science and prejudice. Nietzsche, as mentioned above, demolished that presumption, at least for Strauss. If the rational Enlightenment meant replacing religious prejudice through scientific knowledge and the general illumination of all mankind, Strauss’s ‘Nietzschean enlightenment’ means returning to natural ignorance, the realm of opinion and appearance, the starting point of philosophy, the original cave. The Enlightenment led to the belief that we know better than all those who came before us—a hubris that is still with us. But we do not know, and we must therefore seek. With these reflections, it is no longer necessary to privilege the present as the peak of progress.

The question about the present should therefore “awaken in us the willingness to come out of the cave of modernity.” We can’t simply survey the existing positions, schools, opinions, tendencies, trends, and forces, since—to repeat Strauss’s crucial observation—that may well amount to “describing the interior decor of the second cave”—not to mention that all the existing positions might be wrong and even their synthesis, assuming one was available, could be little more than the multiplication of errors rather than any kind of comprehensive wisdom. The important question concerns neither diversity nor a harmonious unity but only the truth.

If the hubris of a technological society is not to destroy the possibility of being human through ever-accumulating soul-destroying perversions, we must become aware of the shakiness of the foundations of the modern world (the second cave) and, through a return to the primordial question of the right way of life, the Socratic starting point, make ourselves free for the god who, according to another great philosopher of the present, alone can save us now.

This essay appears in the Winter 2023 edition of The European Conservative, Number 25: 46-50.