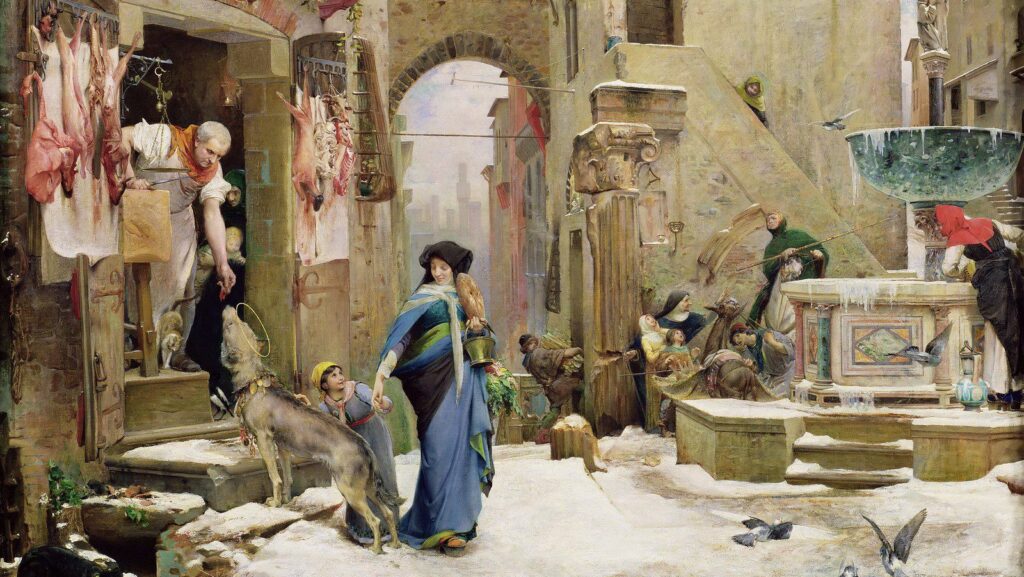

The Wolf of Gubbio (1877), an 88 x 133 cm oil on canvas, by Luc-Olivier Merson (1846-1920), located at Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille, France

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

To many casual observers, politics has become an entirely secular force. The political theologians who once predominated in the history of political philosophy are now amusing vestiges of a bygone era, mythical dressings for the scientific arguments lying beneath. However, venture a little further and it is plain to see that religion continues to exert its influence on political thinkers around the world, including in the West. The prevalence of this theopolitics is not something to be celebrated, confusing as it does the duties of both religion and statesmanship, and doing a disservice to both. To naively ignore this is to open oneself up to all sorts of hidden religious and political agendas.

One such agenda can be uncovered in a series of Facebook posts entitled “Finding Our Religion,” written by the notorious founder of Extinction Rebellion and Just Stop Oil, Roger Hallam. In these posts, he makes explicit that the absence of a public religion in the modern West is a weakness which movements such as his may exploit, and he goes so far as to describe the foundation of a new world religion as the centerpiece of his entire political project. The mythic framing of his planned climate revolution finds its heart deep in the symbolism of a conflict between man and nature under Heaven, lending credence to otherwise distasteful (at best) and extreme (at worst) political demands, which are being accepted and supported by increasing numbers of people. Throughout the Catholic tradition of Europe and stretching right back to the myths of ancient Mesopotamia, the power of this symbolism has proven timeless, and its exploitation should ring alarm bells in the conservative mind.

The tale of St. Francis and the Wolf of Gubbio is one of these examples. It follows Francis after he was robbed by marauders and taken in by the citizens of Gubbio for shelter and comfort. In Gubbio, Francis learned of a wolf that had been terrorising the town, forcing the people behind walls and curfews lest they, and their cattle, be devoured. Untroubled by this seemingly invulnerable beast, Francis corralled a party of townspeople to join him in confronting the wolf unarmed. Using only a prayerful bravery and poetry, Francis not only escaped unharmed, but was able to convince the wolf, after crossing himself, into a contract with the townspeople. It was agreed that the people would feed the wolf everyday, and in return it would cease to threaten Gubbio. After this miracle, Francis departed and the wolf lived among the people for two years until its death, upon which it was buried in a tomb that remains to this day. (Incredibly, archaeological work at the site has uncovered a peculiarly large wolf skeleton there, dated roughly to Francis’ time.)

There are striking similarities—and important differences—between this tale and the Mesopotamian myth of Gilgamesh and Huwawa. This myth, famous for its antiquity, follows Gilgamesh, the King of Ur, and his man-beast companion, Enkidu. The pair ventures into the forests of Lebanon to fell a cedar tree growing there. Using the cedar wood as a devotion to the gods is recognised as a mark of great bravery, strength, and piety, for which Gilgamesh hopes to be immortalised. The king receives the blessings of the sun god, Shamash, as he sets out beyond the city walls. Upon reaching the forest, however, Gilgamesh’s party is magically put to sleep by the forest guardian Huwawa, a ferocious and powerful beast.

Once awake, Enkidu pleads with Gilgamesh to leave the forest, but Gilgamesh declares that he will slay the beast in revenge for daring to strike fear into his companion’s heart. Gilgamesh and Enkidu travel on through the forest, eventually discovering Huwawa in its recesses. Yet, rather than impulsively charging at the beast, Gilgamesh attacks it with a sharp tongue. He humiliates Huwawa for its inhumanity, and then offers it a way out of its wretchedness through marriage to Gilgamesh’s nonexistent sister. Having thus gained the beast’s trust, ridding it of all aura of terror, Gilgamesh strikes. Huwawa is beheaded in a fit of violence—and for this disturbance of the cosmological balance, the gods punish Gilgamesh.

Whilst today the world of beasts, kings, pious men, and their gods may seem a thing of the past, the underlying messages of these two stories is as pertinent as ever. The existential dread of the metropolitan man, surrounded by his un-creaturely comforts, is symbolised in both stories by the wilderness. For Gilgamesh, equipped as a king with the tools of war and subjugation, manipulation and violence seem the adequate course of action. St. Francis, by contrast, responds to the wilderness as a faithful follower of Christ, sewing peace and concord between the world of men and the world of nature through the power of his God.

Today, Roger Hallam seeks to establish a new myth within the public consciousness, in which the members of his various organisations use revolutionary tactics to build higher walls and re-establish curfews to keep the people safe and afraid of the apocalyptic terrors from the natural realm. Hallam’s new world religion holds the perpetuation of the human race as its core dogma. Hallam’s definition of ‘love’ substantiates his thinking: “Love is the process of creating a connection that comes through the disruption of Evil, through the struggle with Evil. True love is manifested as disruption and struggle–it is militant and uncompromising.” Thus love becomes, through this arithmetic, a form of violence. Whilst this argument is by no means unique to theologians, rooted as it is in the ubiquitous concept of a spiritual war between good and evil, it is interesting to note that the act of violence itself (uncompromising militancy) seems to be“the essence of what it is to be human.” Hallam holds his views within a Hegelian framework, but as he himself admits, “To Act is [his] Religion,” so we ought not worry ourselves too much with the finer details.

Indeed, as pagans like Julian the Apostate noted of Christians looking after “not only their poor, but ours as well,” so we might note of climate revolutionaries and their methods: manipulating people with fearful propaganda, demanding lockdowns, aiming to take control of the state, imposing authoritarian rule in the name of the soteriological mission of averting climate catastrophe. Seeing this, I should join Edmund Burke in saying of our preacher, utinam nugis tota illa dedisset tempora saevitae (I wish he had devoted to nonsense all the time he had to spare for violence).

The theme of marriage, and so of love, is of a great significance to both of the stories we have discussed. Gilgamesh offers the hand of a nonexistent sister to Huwawa, recognising the power of love as a rhetorical tool. Francis ‘marries’ the wolf to the people of Gubbio, a contract into which both parties enter willingly and which sees the love of both grow exponentially. More abstractly, the stories depict Francis securing a victory over death through love, whereas Gilgamesh, confronting death with fear and anger, becomes its slave, beheading the beast which ought to have been covenanted with. Our existential fears are ameliorated by the soothing graces of true love, but they exacerbated by the violence of the false ‘love’ of Gilgamesh. Hallam’s ‘religion’ follows in the footsteps of Gilgamesh, aiming this time not to behead Huwawa, but to achieve the freedom of Ur.

It should be clear that Hallam is no more a religious man than Gilgamesh is a loyal servant of the gods, and that the two share the blinders of a political worldview that simply do not exist for a man of faith such as St. Francis. Now more than ever, we are wedded to the wilderness in extreme intimacy. However, this marriage has taken a sour turn and we have grown resentful of each other, doing violence unto one another and forgetting the love that unified us. The duty of religion, not politics, lies in fixing this marriage. Politics speaks the language of violence and control, a language serving its singular aim of preserving the polis. Religion speaks the language of love for the aim of serving God. It is only through this language that we can, as St. Francis did, bring humanity back into harmony with nature. The faithful of the modern world must wake up to the trappings of political theologians and theological politicians, as new ‘religions’ fuse what is Caesar’s to what is God’s. Guilt, fear, and self-hatred, coupled with a love of ‘disruption and struggle,’ cannot fix a marriage. Faithfulness, spiritual guidance, and true love can.