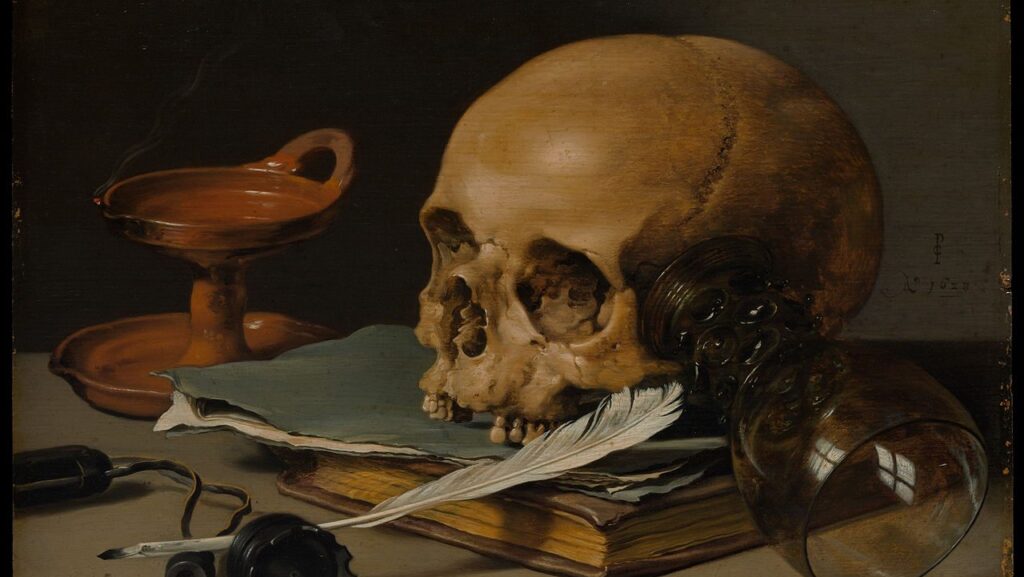

Still Life with a Skull and Writing Quill (1628), a 24.1 cm x 35.9 cm oil on panel by Pieter Claesz (1597-1660), located at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

According to the great Anglo-Irish poet and playwright William Butler Yeats (1865-1939), a man could have either the perfection of his life, or of his work. Evidently, he was something of an exception. In addition to winning the Nobel Prize for Literature one hundred years ago in 1923, Yeats also had a leading role in founding Dublin’s famous Abbey Theatre. He also became one of the first senators in the newly-formed Irish Free State in 1922, where he influenced issues as diverse as Ireland’s educational policy and the images stamped upon the newly-independent nation’s coinage.

Appropriately enough for the season of Hallowe’en, Yeats was something of an innovator in the arena of the occult, which formed a powerful and long-lasting influence upon his life and work. His obsession with such matters began in 1885 when, still only twenty years old and a student at the Metropolitan School of Art, he helped found the Dublin Hermetic Society.

His most like-minded friend at this point was the young George Russell, later to become a talented mystic, visionary, poet, and painter in his own right, under the pseudonym ‘AE’—a kind of minor Irish Blake. In later life, Russell provided an amusing account of one of his and Yeats’ abortive early occult experiments in invoking dark powers. Having first warned those present, with grave solemnity, that the spirits about to be called upon were highly dangerous and had to be treated with the utmost respect, Yeats marched around pointing a ceremonial sword in each direction of the compass whilst muttering what he termed “words of power.” However, just as the demons had been invoked, a knock came at the door. “Oh, here is the tea,” said Yeats cheerfully, and, in Russell’s words, “went off leaving the dread deity undismissed.”

Yeats also made frequent forays into the Irish countryside, often accompanied by his patroness, the aristocratic Lady Augusta Gregory, to record the traditional country-lore of the fast-disappearing Irish peasantry, the poet being especially interested in tales of fairies and peasant-seers. Particularly fascinating to him was the curious fact that these often illiterate and uneducated people had experienced visions of mythological figures and symbols of which it was highly unlikely they could have had any prior knowledge.

Yeats speaks of meeting an Irish seer in 1897 who had enjoyed a vision of the ancient pre-Christian Irish goddess Brigit holding out “a glittering and writhing serpent,” a piece of iconography so obscure that even Yeats, supremely knowledgeable about such matters, had never seen it recorded anywhere until three years later when a specialist book was published containing printed confirmation of the ancient association between the goddess and snakes. Time and again, this same mysterious pattern kept repeating itself. Why?

Yeats, an inveterate systematiser of obscure knowledge, soon devised an answer. During a 1901 lecture, he told a London audience he had discovered evidence of some kind of disembodied “great mind” into which all smaller individual minds, both living and dead, flowed, and which in itself possessed an all-encompassing memory that could be magically evoked by certain symbols. He theorised that visions—of Brigit holding a snake, for instance—were not literally true apparitional appearances before mortals by genuine spirit-beings or deities, but were, rather, symbolic psychological representations of the shared unconscious mind of their parent race, in his case the Irish one.

By the time of his essay Magic, also published in 1901, Yeats had borrowed a term from the ancient Neoplatonist philosophers he so admired, the anima mundi, or ‘soul of the world,’ to describe this great mind. He was also claiming that magic itself—defined, for present purposes, as the conjuration of spirits—was only “what we have agreed to call magic.” Yeats believed that “magic” was actually an entirely natural phenomenon, broken down into three key laws:

(1) That the borders of our mind are ever shifting, and that many minds can flow into one another, as it were, and create or reveal a single mind, a single energy.

(2) That the borders of our memories are as shifting, and that our memories are a part of one great memory, the memory of Nature herself.

(3) That this great mind and great memory can be evoked by symbols.

Symbols can be many things, but, as befits a poet, for Yeats the most powerful symbols were words. In his youthful attempt to conjure demons with George Russell, he uttered magical words—“words of power”—to try and achieve his goal. He soon concluded that the most powerful of all words of power were those to be found in his own poetry.

Yeats came to conceive of all truly great poems as something akin to magical spells of conjuration, drawing down “what I must call … spirits, though I do not know what they are” into the very soul of the reader. In his essay The Symbolism of Poetry, Yeats applied this idea not just to poetry, but to all other artistic fields of endeavour as well: “All sounds, all colours, all forms, either because of their pre-ordained energies or because of long association, evoke indefinable and yet precise emotions, or, as I prefer to think, call down among us certain disembodied powers, whose footsteps over our hearts we call emotions.” For Yeats, a poem is now not simply a poem, but also a magical tool; but how would such a thing work? Why would the phrase “red, red rose,” for instance, be able to call up a disembodied ghost in order to temporarily influence the reader’s emotions?

In Magic, Yeats explains further that the power of poetic phraseology has its origins in age-old “racememories” stored in the anima mundi which, due to their presence there, can still influence modern man. According to Yeats, “Whatever the passions of man have gathered about, becomes a symbol in the great memory, and in the hands of him who has its secret [like a poet] it is a worker of wonders, a caller-up of angels or devils.” However, confusingly, “the symbols are of all kinds, for everything in heaven or earth has its association, momentous or trivial, in the great memory, and one never knows what momentous events may have plunged it … into the great passions.”

Consequently, a poet never quite knows which precise words will summon up which precise spirit or vision; combinations of words must be experimented with in order to create that which casts the strongest spell. Those combinations which work best poetically, evoking the most profound or beautiful response in the reader, must also be, by definition, the most magically potent.

Yeats even claimed that the folk-cures of the Irish countryside, with their apparently random combinations of materials, must function in a similar fashion: “Such magical simples [cures] as the husk of the flax, water out of the fork of an elm-tree, do their work, as I think, by awaking in the depths of the mind where it mingles with the great mind, and is enlarged by the great memory, some curative energy, some hypnotic command.”

Rather than poets casting their beautiful magic on the spirits through the medium of the anima mundi, maybe the spirits were casting their magic on the poets via the very same means? Yeats’ poem “The Cap and Bells,” originally published in 1893, is upon first glance a confusing tale about a jester walking in the garden of a beautiful lady’s house, divesting himself of both his heart and his soul. Clothed in “quivering red” and “straight blue” garments respectively, he sends them both flying up towards the maiden’s window, whereupon she rejects each of them. However, she then gladly accepts the jester’s traditional hat—the cap and bells—and all seems to end happily ever after with the pair.

Yeats claimed that he did not understand the meaning of “The Cap and Bells” because, rather than having written it himself, it was instead written for him, by ghosts. He had “dreamed this story exactly as I have written it” one night, and he remained puzzled by its content ever afterwards: “The poem has always meant a great deal to me, though, as is the way with symbolic poems, it has not always meant the same thing. Blake would have said ‘The authors are in eternity,’ and I am quite sure they can only be questioned in dreams.”

Eventually, Yeats questioned if any poet had ever truly written any of their own poems, speculating whether Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale” had already pre-existed its earthly writing by having been stored somewhere within the anima mundi, meaning the poet himself had been little more than an unconscious medium for the spirits’ authorship. Yeats even went so far as to say that, “If Homer were abolished in every library and in every living mind the tale of Troy might still appear as a vision.”

Yeats therefore became naturally predisposed by his occult researches to the whole idea of taking seriously the practise of automatic writing (when psychic mediums claim to enter a trance, allowing spirits to control and communicate with the living via their pens). Indeed, by 1913 he was actively seeking ghostly advice about his personal life.

Yeats had then been conducting an affair with a 38-year-old actress called Mabel Dickinson. In late May, she wrote to tell him that she was pregnant. Seeking advice, Yeats visited Bessie Radcliffe, a favoured medium. When asked for advice about Dickinson’s apparent pregnancy, Radcliffe’s spirits replied through her pen that the poet would do well to be cautious in the matter: “Deception, Deception, Deception, you have said; you are right—Refrain, Refrain, Refrain.” The spooks were right, too: Dickinson was not pregnant at all, just desperate for marriage with a famous man. Yeats broke off the relationship and began trusting the scripts from beyond to an ever greater degree. This was presently to have some very odd repercussions when he married a young woman named Georgie Hyde-Lees.

Yeats married Hyde-Lees in 1917, when he was 52 and she only 25. Theirs was not, initially, a happy union. The love of Yeats’ life had been Maud Gonne, a well-known Irish nationalist and famous beauty, who had ultimately rejected him. He seemed to have more luck with Maud’s daughter, Iseult, who, in 1915, at the age of 20, suggested to Yeats they should marry—yet her unspoiled youth was not Iseult’s only attraction to the older man.

Iseult had been conceived by Maud Gonne in some very strange circumstances with the French anarchist, Lucien Millevoye. Their first child together had died in infancy; therefore, in a bizarre and macabre attempt to reincarnate the baby, the couple had sex in the vault under the dead child’s grave. Maud became pregnant with Iseult, and Yeats, with his esoteric bent, would have been only too glad to marry such an unusual, supernaturally created being. However, by 1917, Iseult had decided that Yeats was simply too old for her. Yeats’ marriage to the only slightly more mature Hyde-Lees, a sometime fellow-experimenter in occult matters, was performed very much upon the rebound.

Predictably, things soon went wrong. Yeats plunged into a psychosomatic depression and felt too weak to consummate the union; all seemed over before it had even begun. But then, in October 1917, not quite a week after the wedding ceremony, Georgie suddenly felt an uncontrollable need to take up pen and paper—whereupon she found that she too could practise automatic writing, just like Bessie Radcliffe.

Yeats was delighted. All of a sudden, his wife held a new interest for him, and entire evenings were now spent side by side, with Yeats asking Georgie’s ‘Instructors,’ as they called themselves, to impart valuable information from the ‘Other Side,’ drawing the newly-weds closer to one another and creating a strange spiritual bond between them. In the words of Yeats’ biographer, R.F. Foster, “It is clear that through this strange process the principals were getting to know each other for the first time.”

Perhaps the couple should have done this before they got married, but never mind. The ‘Instructors’ wisely advised Yeats to stop brooding upon his lost love Iseult, to take more exercise, and to give poor Georgie some children to brighten up the place. They even ordered him to stop bothering his wife for more spirit-communications when she was menstruating! It is reasonable to suspect that Georgie was the source of these messages, an idea given more credence by the apparent existence of a separate breed of spirits from the ‘Instructors’ called the ‘Frustrators.’ These ghosts, whenever Yeats asked his wife questions about matters she had no direct knowledge of, would conveniently step in and say “No, I may not speak of these mysteries.”

Yeats’ superstitions were a noted public joke: supposedly, he once cut a hole in his unworn coat rather than disturb a black cat sleeping on top of it in order to avoid bad luck. Was Georgie’s automatic script all simply an act of manipulation upon her part, a cry for affection from a distant husband? Not according to Yeats, who reported odd paranormal flashes of light, disembodied whistling, music and spirit-voices, strong scents of flowers coming from nowhere, and sightings of apparitions during his shared spousal séance sessions.

Furthermore, there was the extreme complexity of the bizarre yet internally coherent philosophical system the spirits spent much of their time communicating through Georgie’s hand, whose basic central tenet was that good and evil ages, known as ‘gyres’ with their corresponding figureheads (chiefly, Christ and Anti-Christ) alternated and ruled over mankind in periods lasting for two thousand years apiece. This ghostly philosophy, as later systematised by Yeats in two different major versions of his book A Vision, was to become a central theme of his poetry; many of his key works, like “The Second Coming” and “Leda and the Swan,” two of the most famous poems of the twentieth century, simply cannot be properly understood without knowledge of it.

Many of Yeats’ modern readers do not have any knowledge of his philosophical and occult beliefs, however. W.B. Yeats is, of course, still remembered, but he is increasingly often viewed as Ireland’s national poet in a purely political sense (not without some good reason, given that he obviously did write about political themes in many of his greatest works, such as “Easter 1916”). As one who helped conjure up the modern Irish Free State, creating a sense of anti-imperial consciousness amongst the locals to inspire them to cast off the yoke of unwanted rule from London, he fulfils a convenient anti-colonialist role to today’s tediously over-politicised cultural gatekeepers. Even Jeremy Corbyn is an enthusiastic fan.

Today’s left-leaning literary academics, with their usual Marxism- and scientism-derived materialist philosophies and views, seem rather embarrassed by Yeats’ occult connections and concerns, and so they frequently avoid writing about them whatsoever. When considering the fact that these unorthodox beliefs helped influence his idea of nations and peoples having innate ‘racial memories,’ it is a wonder that Yeats has not by now been cancelled by academia altogether. But how deadening a prism through which to view such a great poet. This Hallowe’en, even those who do not believe a word of Yeats’ strange, sublime philosophies might wish to enter into a state of temporary disbelief, and re-read some of his works anew as if they were true.

Does it matter, in the end, whether Yeats’ wife’s automatic writing, together with her spooks, were genuine or not? The most significant result of Georgie Hyde-Lees’ spiritual scrawling was not simply to trick a credulous old man into being a better husband, but to spur that same man on into creating some of the greatest lines of verse ever written. As the dire political pseudo-poetry pumped out today by blatant agitprop ideologues like Ka(t)e Tempest, Benjamin Zephaniah and George the ‘Poet’ [sic] so capably shows, it is difficult to write poetry of genuine worth without belief in some kind of invisible realm beyond the human to inspire the feat in the first place, the occasional exception like Philip Larkin notwithstanding.

When asked by Yeats why it was, exactly, they had chosen to communicate with him, his unseen ‘Instructors’ memorably answered, “We have come to give you metaphors for poetry.” If so, then they certainly succeeded—and what poems they were, too.