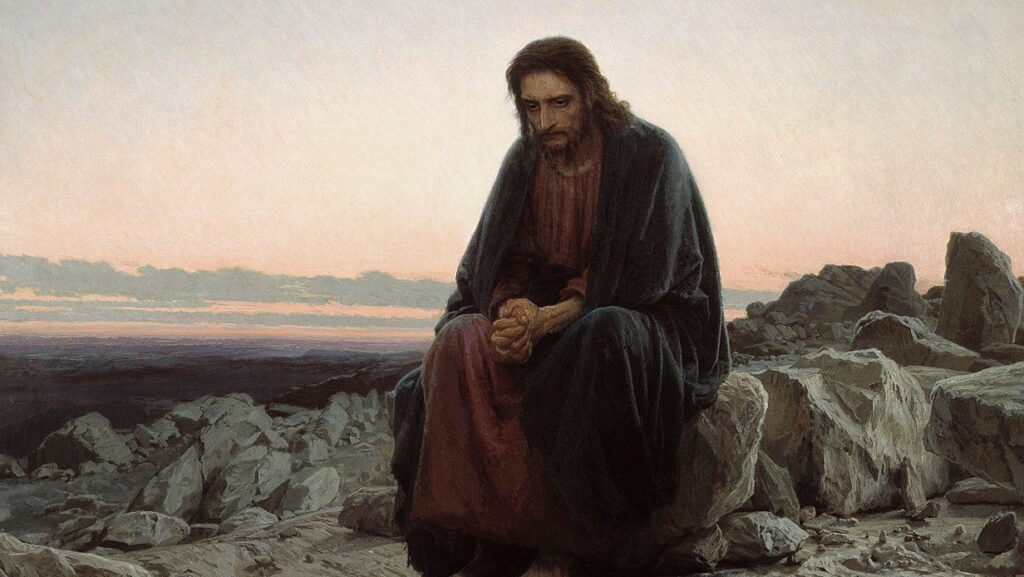

Christ in the Wilderness (1872), a 184 cm × 214 cm oil on canvas, by Ivan Kramskoi (1837-1887), located at the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

History is complicated. Any attempt to provide a swept clearing must, perhaps, transmute its subject-matter into the nodes of an imaginary, lit by the foreign lights of today. However, it would seem altogether more foolish to make no attempt to clear the leaves, since our civilisation does appear to be in autumn. I hope that recognition of the importance of my theme—namely, Christianity—will forgive the anachronism of mono-angular treatment.

The basic intuition of this article is that the Christian religion is in a fundamental sense a minority religion. This is not to suggest that it does not tend towards, or that it cannot form, establishment. Rather, the point is that Christians reflexively assume that they will be in the minority. This means that the Christian does not depend, for the continuation of his faith, upon the assent of others. Jesus says, with myriad analogues:

If the world hate you, ye know that it hated me before it hated you. (John 15:18)

It is not my concern to discuss the veracity or the merits of Christianity. Of importance in this article is the fact that Christianity (and the Christian) presumes a state of alienation in the world. They expect to be aliens, and indeed if anything are concerned when they are not alienated (e.g. Luke 6:26). This is a more complicated position than it might first appear. What, after all, is the world? For the purposes of this article, I simply wish to point out that Christians do not depend upon their neighbours’ good wishes, let alone active support, to remain faithful. The Christian is in this sense, then, an ideal member of a ‘pluralistic’ society.

I want to suggest, in a reversal of this latter statement, that ‘pluralism’ as understood in modern parlance is a kind of post-Christian confusion. The Christian may not only be an ideal pluralistic citizen, but perhaps the ideal pluralistic citizen. On this view, pluralism would be the extension of a Christian consciousness to inhospitable forms of life. That is to say, it would be the transference of an expected social-psychological independence, not insensible with Christian people, to include non-Christian people. Pluralism falsely universalises the very unusual social-psychological qualities of Christian life.

To provide historical support for this claim would require an immense amount of research, which I cannot claim to have done. It is, nevertheless, a lingering intuition which I wish to share and expound.

A basic premise of my position is a conservative one. That is, the natural form of human life is communitarian, not pluralistic. This I will elaborate, before sketching those which I take to be the Christian and faute des mieux liberal pluralistic positions. To argue that human life has natural and inhospitable forms, however, is to impute some kind of purpose to it. I am considering, here, the conditions of personhood, and must first explain just what a ‘person’ is.

Loosely speaking, the classical (viz. Platonic, Aristotelian, etc) view is that coherency of orientation is not a given. Consider, for a moment, somebody who is addicted to drugs (or indeed to any substance or behaviour). A feature of their being addicted is that they are not in control. They cannot say ‘I will do X’ and then reliably do ‘X.’ In other words, their words have ceased to be a reliable indicator of their actions, both to others and to themselves. They are self-alienated. In a disturbing sense, they have lost their personhood (although they might regain it).

This is a terrible fate to befall anyone. For Plato (and for many, many others), the human being is a kind of separation of ‘rational’ and ‘animal’ (for the sake of simplicity, I will avoid the ‘passionate’ element of his ‘tripartite soul’; suffice to say, it serves, broadly, as an ally to either the rational or the animal). The animal part, with its drives (e.g., for food, for sex, for sleep, and other such animal needs), threatens to override the rational. In cases of such overriding, the human being becomes, curiously, both completely predictable and completely unpredictable. They are predictable, because they are merely natural. By the same lights, they are completely unpredictable to someone else because, in the total absence of rational powers, their words are not properly speaking words; their speech loses all revelatory quality, because they have no power to override their drives. They do not, in this sense, exist as a person. In this sense, Platonic philosophers say that they do not have “being,” which one can read as something like “coherency.”

It is something like this position that we encounter at the close of Book I of Plato’s Republic. For Plato, the matter of coherency is bound up with the question of justice. To gloss the point, it is impossible to be coherent without being coherent about or towards something. This ‘about-ness’ or ‘towards-ness’ is, for Plato, evaluative, since the regarding of certain objects as worthy of attention requires a value structure; one might even say that it is, or at the very least exhibits, a value structure. In other words, valuation is a condition of psychological order. Personality, in short, is contingent upon valuation. Pluralism, in making claims about the conditions of valuation (in its case, there are none), makes claims about the conditions of personality (which is to say, again in the case of pluralism, that the person exists a priori). To use a slightly different idiom, the ability to say “I”—and to act with the consistency which gives reality thereto—is not dependent upon anything one might call society or custom or family or God. The “I” is simply and categorically the “I,” as Fichte pronounced in 1794. Put baldly, pluralism assumes that man is begotten, not made.

It is often said, with some justice, that while liberals believe that the person exists before society, conservatives believe that the person exists therethrough. The conservative view of the world includes the position that communitarian conditions obtain for the individual’s fulfilment. In different language, the conditions of valuation are communitarian. Personality is, as it were, out-sourced. Put in the reverse, the political order is credited with containing (or as itself being) ‘mind,’ the social substance in which individuals are involuntarily immersed and thereby become themselves.

‘Mind’ here means something like ordered attention. It is in this sense that Hegel, for example, saw the state as Mind on earth and freedom as, therefore, impossible outside of the state. That is, the state—precisely because it furnishes the conditions of psychological coherency (viz. personality)—is itself deemed personal. On an abstract account, the state comes to be thought of in personal terms, and indeed as itself a kind of ‘subject.’ On a less abstract account—speaking internally, that is—it is perhaps not so silly to represent the state as a person: a king, or a spiritual father or mother (Uncle Sam, Britannia, etc). The land, too, becomes spiritously personalised (e.g., Abendland or Tamesis). Pagan ancestor worship, and talk of genius loci, comes to look not so irrational as it first appears to modern eyes. In other words, Hegel is not so dissimilar from Aristotle, who meant something very much like what I have recounted above when he described man as essentially a political animal. Of course, to see God the Father as the personal, universal custodian of the nation is not a difficult metaphysical extension, even if an epoch-making moral shift.

Recognising the personality of the state as a central concept of conservative political theory makes intelligible the central role of piety in the conservative ethic. Piety is the respect considered due to the sources of the individual’s life: family (especially the father); the institutions of the city; and one’s ancestors, both familial and civic. This stance presumes the existence in all these objects of the quality of subsistence through time and the capacity to receive praise and blame. In other words, to think of these objects in personal terms is appropriate. The position perceives the king (or, in modern times, the state) in terms of one’s own father. Authority on these terms is understood as the image of the father. A good ruler, then, is a king (who is qualified by the love of the father for his people qua family) and a bad ruler is a tyrant, who is a usurper, and is not like a father (see Aristotle’s Politics, Book I). The gods, likewise, are considered to be attached to the form of life of a people. They are, as it were, patron gods: gods of an ethnos, or a city, or a household. Ancestors, moreover, are absorbed into the metaphysical self-image of the people, as chthonic deities co-mingling with their divine, patron spirits. Burke’s expression of the state describes, inadvertently perhaps, the pagan world rather well: a transcendent bond between the dead, the living, and the unborn.

It is worth emphasising the essentially communitarian (viz. profoundly non-individualistic) conception of life. Individual fulfilment, whilst not a foreign idea to the pagan world, is always conditioned by and inseparable from community. Aristotle’s famous conception of eudaimonia is dependent upon the shared sense of justice which, in his view, constitutes the state. The individual’s reason is essentially an extension of the state’s, much as a flower grows from the in-dwelling vitality of a plant.

This key point about the formation of mind is a useful point of departure for the discussion of Christianity. Reason, from the conservative point of view, is fundamentally out-sourced; and reason, considered in this physical sense, is also personal. It is the person of an authority figure. This, I suggest, is the anthropologically typical form of society.

Christianity, altogether radically, does not depend upon communitarian supports. The Christian believes themselves capable of engaging with God at any time, anywhere, and without others’ encouragement. It is the psychological coherency (one might say, the sanity) of the Christian which proves him right or wrong.

There is a certain analogy, here, between Platonism and Christianity. Platonists believe, also, that an individual has access (contingent for the Christian upon their willingness and for the Platonist their aptitude) to Mind universally. In other words, personality is an effort dependent not upon the state, but an ascent undertaken by the individual. The state, therefore, is dependent (insofar as it is rational) upon the Founder, for Plato the “Guardian class.”

It is perhaps worth making some distinction between statist and anti-metropolitan forms of such a priori rationalism. That is, Christianity has sometimes been expressed as a fervent rejection of civilisation, or at least seen that rejection as a necessary trial or political possibility (see e.g., the Desert Fathers, mediaeval monasticism, St John of the Cross’ Ascent of Mount Carmel and other works of mysticism; indeed, Genesis 4:17 claims that cities, other than Jerusalem, are founded by Cain, who wasn’t very nice). Plato’s Republic finds no equivalent in Scripture, which never approaches the state as designed so much as received. Solitude, nevertheless, is a feature of Platonism as well as of Christianity, and it would be incorrect to assert that Platonism must necessarily receive statist expression. The principal distinction between the two, in my view, is a matter of metaphysical personhood. Platonism does not see reality as fundamentally personal. By extension, it is impossible, in my view, to be a conservative (in the manner I have thus sketched) and a Platonist, because personhood for the Platonist must resolve into abstraction. Of course, a Christian Platonist can be a conservative, but then they are not a Platonist anymore.

The Christian is not dependent upon finding Mind about them, in custom or otherwise, but claims transcendent access. In being dependent upon no horizontal relations, there is no out-sourcing of Mind. Indeed, where conservatism out-sources the mind, we might say that Christianity in-sources it. The Jewish people—out of which religion Christianity claims extension—are distinct in the ancient world for their following neither a tree spirit, nor Odin, nor Arminius, but a book. Authority is not, then, the image of the father, but that which is written. Put differently, Mind for the Jews is conceived not in familial terms, but in abstract terms—except, of course, for the personalised way in which the book is conceived as coming down from a personal God. The wealth of family pronouns in Scripture—Old and New Testament—places a value upon the family structure as a condition of God’s intelligibility. As such, one must not overstate the gulf between Christianity and paganism. More politically speaking, I am saying that I think that Christianity is more conservative than it is liberal. That is, the bible seems to presume the naturalness of the conservative position, by virtue of making familial structures and other intergenerational traditions a condition of Scripture’s intelligibility. Nevertheless, of pivotal significance, the Christian is not dependent upon earthly fathers for his sanity. Christ even says:

If any man come to me, and hate not his father, and mother, and wife, and children, and brethren, and sisters, yea, and his own life also, he cannot be my disciple. (Luke 14:26)

It would be a strange interpretation to suggest that what Jesus is really talking about here is liberal pluralism. Nevertheless, does it not indeed follow? Consider the following verse:

And whosoever doth not bear his cross, and come after me, cannot be my disciple. (Luke 14:27)

The argument made at the very least includes the notion that psychological coherency does not depend upon the acquiescing, let alone the support, of other people. It is sufficient to follow Christ.

Christianity, of course, makes an even stronger claim. Namely, that Christ is not an alternative to the city gods, but the only option, “for without me ye can do nothing” (John 15:5). Until, however, Jonah 4:31 comes to be true, and people cease “to know their right hand from their left,” this is harder to believe.

My argument is that liberalism (viz. pluralism) assumes the possibility of psychological coherency without father, mother, wife, children, brethren, and sisters. It has inherited a Christian psychology but, having jettisoned the Rock of Ages, built its political theory upon the sand. Put in the language of this article, it in-sources the mind. Another way of saying this is that, fundamentally, man can choose his own values. He is, therefore, non-contingent. He exists before society and, if anything, is its condition.

Reason, that purest pursuit, can be a kind of comfort from mortal dross. In times of darkness, one may withdraw into an inner light, much as gaining perspective, and somehow remain unscathed of trauma. Hannah Arendt makes the distinction—following, I think, Karl Jaspers—between loneliness and solitude, where the former is the truncating (a depersonalisation in the sense of a dulling) of mind by isolation and the latter is a kind of transcending. More bathetically, Sherlock Holmes in the series Sherlock withdraws into his ‘mind palace’ where one finds not only the vantage point for clear thought—that is, thought cleansed of the moment—but also warmer objects, namely the dog of his youth, lit by the ostensibly eternal light of contemplation. Reason, as every man’s upper room, is a source of moral power, much as ringing a friend on a bad day. In this home, untouchable from the change and decay which in all around one sees—above the confused alarms of struggle and flight—a choice selection of the living and the dead serve a daily bread amidst ordinary suffering.

Harry Potter provides the same sort of argument. Harry gains courage, in the final moments before the giving up of his spirit—before, of course, their poetically-necessary absence, when the garden breaks into the clearing of decision—from the real ghosts of his parents and friends. Or again, consider how the Jewish man in hiding, Max, in The Book Thief, speaks fondly of the power of music and, more especially, how nobody can take it away: for it exists in here. Mind is in-sourced. This is the liberal view.

This is a politically-loaded position to adopt. It is perhaps worth mentioning that, for all the in-sourcing, viewers of Sherlock, Harry, and Max, are expected to affirm and support the leading protagonists. Their values are generally inoffensive, insofar as they are discernible. Put more forcefully, it may simply not be, as it were, a fair test. If one seeks to uphold such positions as Harry does (e.g., Voldemort is evil) then one is unlikely to encounter much moral opposition, not least because he doesn’t have a nose and looks like a pickled egg. The matter is quite different if one supports hyper-controversial positions, such as not giving sex-change hormones to children under 16.

Those who opposed the Nazis did so not from the strength of music or the love of dogs, but from—to an historically astonishing degree—the love of Christ or a fervent belief in Marxism which, whatever one says about Marxism’s moral poverty, imparted real courage to some of its adherents. The political prisoners of the Nazi camps testify to the moral purpose and physical strength born of in-sourcing the mind under a regime in which opposition to Nazism carried the highest social cost. It is liberal propaganda, I want to say, to suggest that Nazism was opposed for love of “music” or other such empty vessels. There are, of course, exceptions, but I am interested in the normal. It is propaganda because, if this is true, then pluralism is possible. Or rather, this must be true, for pluralism to be possible.

It is my part prediction, and part (rationalised) experience, that the natural person (which is to say, the normal person) craves affirmation from others. The upholding of values, which is a condition of psychological coherency, requires either a communitarian context or real belief in a God (in this sense, those so possessed by Marxist doctrine that they would go to work-camps for it, ought to be called religious, their protests notwithstanding). Pluralism is built on the falsehood that either one can pick one’s own values or, more sophisticatedly, that everyone is possessive of an inner light like Sherlock, Harry and Max. This latter position, though appealing, is I think fanciful. It pretends to the psychological strength of Christian faith, whilst removing all of its substance. The fact is, man’s mind is cold, and he needs and craves warmth.

One can expect, with some sadness, that the illiberality of liberalism will only grow worse. Pseudo-communities will form, made up of dissenters who, having rejected the communitarian position (viz. the orthodoxy), will recruit for the purpose of mutual assurance and thereby psychological coherency. The LGBTQ ‘community’ is a project of reassurance, as the proliferation of rainbows is an attempt to coronate certain desires as values, by their affirming reflection all around. It is a doomed attempt, having left home, to feel at home in the desert.

The cost of the epidemic of psychological incoherency is depression and suicide. It is increasingly common for liberals to choose their friends according to whether they voted for Hilary (or newly, Biden), or Remain (in the Brexit context). Conservative thoughts are rapidly becoming not only unacceptable but illegal and the targets of real hatred. This is to be expected, and it is nothing short, in my view, of the natural, in many ways deeply conservative tendency towards establishment for the sake of forging the conditions of personhood. Natural man cannot abide disagreement, and only unnatural men (see 1 Corinthians 2:14) can make pluralistic societies. Homelessness leads, as a drowning man pushes down his compatriots, to mortal violence.