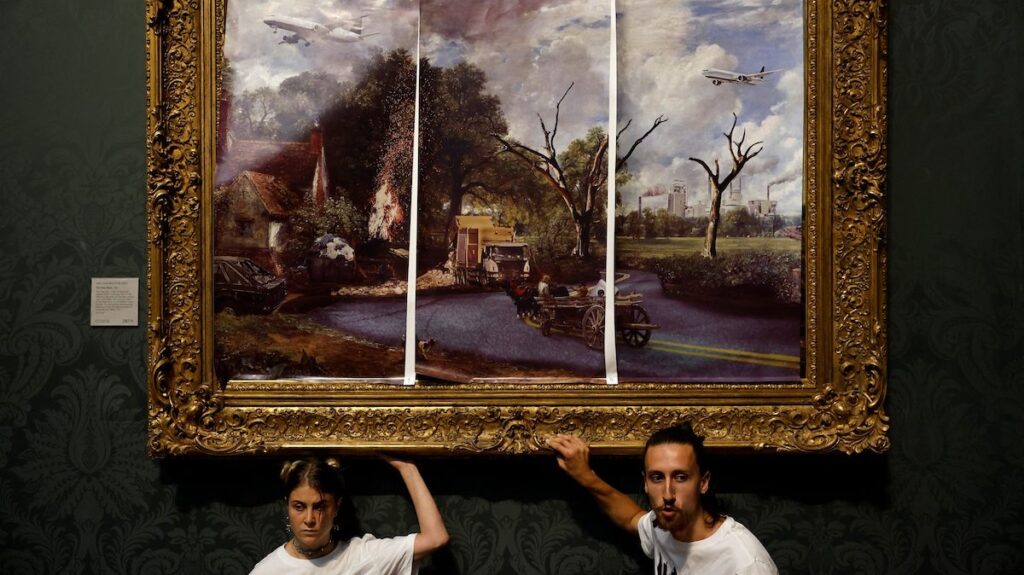

Activists from the ‘Just Stop Oil’ domestic terror group, with hands glued to the frame of the painting The Hay Wain by English artist John Constable to protest against the use of fossil fuels, in the National Gallery in London on 4 July 2022.

Photo by CARLOS JASSO / AFP

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

In the historical struggle over images—iconomachy (Eikonomachía)—there is no doubt that in the Christian West the iconophiles were victorious. That said, Byzantine defenders of holy representation could not possibly have foreseen how, and to what extent, the eikon would lose its moorings. The complexities involved in worship, the fear of slippage between revering what the icon represents and worshipping the icon itself, are, to us, largely a distant debate. Deluged by icons and images of all kinds, our era is without distinction and without judgement. The separation between the holy and profane, let alone the quality of our attention, is eroded to the point of absurdity. Conditioned to respond with numbness and indifference, if only to protect ourselves—of course I can cope with pornography, horror, and whatever demonic amalgams AI throws up!—our own capacity to imagine is stuffed full of outside, and largely hostile, effigies. The era of total, infinite secular representation is upon us—yet the deeper anthropological (and religious) question of how humanity should understand and treat images has never left us. Nor have the periodic, spasmodic desires to destroy them.

What’s worthy of note is how our current moment manages to incorporate iconoclasm within itself, as part of the condition for the production of images itself. While in Afghanistan the Taliban has recently resurrected edicts against images of all living things, in the West there are new outbreaks of iconoclasm—a war on beauty, as well as the more obvious direct political attacks on art and heritage by activists. At the same time, encompassing these movements is a paradoxical iconophilia that carries within it an iconoclasm and a desire to destroy even the possibility of images of the good. This plays out in the erasure of the human face, in particular in ‘flat design,’ the propagandist style of the DEI regime, but also in the continued levelling of sacred images and the ongoing attempt to replace religion by art and culture. As a mode of resistance, new ‘icons’ (memes) have emerged, and have been heavily censored, revealing the fear of their power. As Jean Baudrillard put it:

One can see that the iconoclasts, whom one accuses of disdaining and negating images, were those who accorded them their true value, in contrast to the iconolaters who only saw reflections in them and were content to venerate a filigree God.

We have seen multiple attempts to erase history itself, and begin again at year zero, as highly-motivated activists seek to dethrone reminders of humanity’s past: slave-traders, confederate generals, and other ‘bad’ founders are desecrated and torn down, as if part of a bid to iconoclast history itself. As Harrison Pitt put it in this publication: “There is a politically correct hatred for Western civilisation as its own perpetual forge of human idols, a distinctly Puritan sense that no historical figure is pure enough to merit a statue.” Pitt notes, however, that the earlier so-called Puritans were nevertheless at least “serious people who stressed the relationship of the individual to God” and extolled “virtuous self-rule and ethical responsibilities.” Today’s iconoclasts seek little more than a photograph in the newspaper, if not a prison sentence—think of the media-ready antics of Just Stop Oil, throwing soup on Van Gogh or spraying Stonehenge with orange paint. Any attention they might lend to their cause is smothered in a self-serving narcissistic love of the image of themselves destroying images (or performing destruction, indifferent to whether damage is actually caused).

In an open letter addressed to the judge in the sentencing of the Just Stop Oil pair charged with inflicting criminal damage on Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, various professors pleaded that “It is our expert opinion that it would be incorrect to consider this JSO action, and its social message, as an attack on an artwork from without. Instead, it belongs to the well-established tradition of creative iconoclasm.” This cunning argument did not, however, prevent the judge plumping for jail-time for the plucky young creative iconoclasts. Still, the intertwining of iconoclasm with art itself by the letter-writers is enormously revealing. It tells us something we know but can’t always articulate about the modern visual realm, in which the image war continues but under the cover of an apparent welcoming of and supposed indifference to all images. This indifference is, I suggest, a cover-story for a deeper knowledge that there really are distinctions to be made between good images and bad: but the confusion is the point here. Images are bewitching and seductive, and our attention is finite. Restoring awareness of the power of imagery is key to escaping nihilism.

As well as demonstrating the sheer love of destruction for its own sake, it must be remembered that iconoclasm, whether religious or political, has historically generated new institutions, some of which have become revered in turn, in a paradoxical iconoclastic-iconophilic hall of mirrors. In the battle over the Christian control of images and art, the contemporary art gallery and the museum, most notably, are the products of and coterminous with revolutionary and desacralizing activity. When the Louvre opened in Paris in 1793, it was as a dumping ground for what the revolutionary Monuments Commission and the Temporary Arts Commission dubbed symbols of “royalty, feudalism, and superstition.”

Knowing full well the worth of religious and aristocratic objects, the French revolutionaries had to come up with a solution that both protected at least some of the most valuable artefacts while simultaneously depriving them of their religious, genealogical, symbolic, and historic power. As Stanley J. Idzerda puts it: “Regarded in this light, the public museum may be said to have originated as both an instrument of and a result of iconoclasm.” Art becomes a direct rival to the church, and to the forces of conservation and tradition, the moment the ecclesiastical grip on images and their place in the visual and spiritual order weakens. This in many ways is the appeal of the arts: the free-play of iconophilia, but stripped of order, transcendence, and verticality.

A Sunday trip to Tate Modern, which opened in May 2000, to see art that provides moral instruction according to the fashion of the day—that celebrates ‘marginalised’ identities perhaps—provides a very clear indication that secular art and cultural organisations strive to replace religious forms. A silent disco held in Canterbury Cathedral earlier this year rammed the message home: there is no place too sacred for the omnivorous energies of ‘progress.’ Contemplation means gazing at a secular work of art, not sitting quietly in prayer. And churches are simply art galleries in waiting.

As Reverend Jenni Hogan, Chaplain at an art college, noted on the tenth anniversary of the Tate Modern’s opening: “Visitor numbers at art galleries are soaring, whilst church attendance dwindles to dangerous levels.” Her proposed solution, namely that “the church should ditch any fear of the contemporary art scene and make a place for it in hallowed spaces,” is, I suggest, too weak and, in any case, too late. There are of course better and worse ways of doing things, and organisations like “Art and Christianity” are perhaps more attuned to the dangers of making church into simply yet another progressive place where anything goes.

But the issue here is deeper: the new iconoclasm-iconophilia embraces the collapse of any distinction between the sacred and the profane, the holy and the secular, and naturally seeks to create new icons while erasing proscribed groups and sentiments. Here we are dealing with the intra-iconoclasm of the regime itself, indissociable from metaphysical propaganda. This manifests itself in the deliberate replacement of the human as idiosyncratic ensouled individuals with images of bearers of categories of an administrative type.

Visually, we are probably all familiar with a style identified by design critic Eli Schiff as “humans of flat design.” This ubiquitous 2D, often faceless and eyeless, mode of illustration, presents people without character. Often limbs are distended, and multiple colours used to demonstrate ‘diversity’ without specificity. These are ‘every people’ but also ‘no people,’ city-dwellers looped into technology, and superficially diverse but absent any specificity. The absent, and often masked, face is not accidental. As the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben puts it:

Precisely because the face is solely the location of truth, it is also and immediately the location of simulation and of an irreducible impropriety .… Politicians, the media establishment, and the advertising industry have understood the insubstantial character of the face and of the community it opens up, and thus they transform it into a miserable secret that they must make sure to control at all costs.

This administrative worldview as a mode of thinking and representation was manifestly humiliated in the recent U.S. election when many people who were supposed to vote in accordance with their imputed bureaucratic type—race and sex—manifestly and rebelliously failed to do so.

Against the backdrop of the regime’s iconoclasm, the reality of human difference, and our belonging to specific traditions and backgrounds, I want to draw attention to a subterranean and paradoxical tradition and simultaneous counter-tradition that constitutes a visual and social resistance to the HRification of our lives.

While we may note with a wry smile a certain difference in the quality and the dedication of labour, both memes and illuminated manuscripts are largely produced by anonymous, unmarried, young men with a belief that the world as it presents itself is not the whole story and may even be quite evil. Opposed to the top-down facelessness of regime ‘art’ we have another kind of image-production where anonymity, or the absence of a name or an identity—of monks and meme-makers alike—is put in the service of a higher truth. There is no doubt that the playful, irreverent power of memes, as well as the counter-worldly values of Christianity, are deemed subversive by the current liberal order. It is clear from Google’s search warning, launched last year, that “memes about groups of people might be disturbing or hurtful” that there are strict rules about which modes of categorising are acceptable. Similarly, if you search for “christcore” or “tradwave” on Instagram, you will read the alarming note that these terms “may be associated with dangerous groups and individuals.” These alarm notices are clear admissions that the liberal order understands very well the power of both the form and the message of non-compliant art, and that Christian iconography, however futuristic in design, is a threat to a world that prioritises desire and identity over self-renunciation and charity.

We are here confronted with what the great art historian Joseph Koerner describes in relation to the notably pseudonymous Hieronymus Bosch as “enemy painting.” As Koerner puts it: “Bosch approaches the point where the symbolism of evil becomes an evil symbolism, where mere pictures of an enemy become enemy pictures … Bosch does something different than disenchant. … [His works] immerse us in what we know to be deception, slander, and false testimony, where nothing is as it seems.” He then elaborates: “Whereas in his other works he painted enemies and their imagery, in the so-called Garden of Delights Bosch created an enemy image, a painting posed—playfully and cruelly— as if it were meant to ruin someone, perhaps especially its beholder.” Battered and distracted by images created by our enemies and designed to demoralise, we can learn from Bosch’s technique and imagine enemy photography, enemy cinema, enemy ballet, and so on, which turn secular propaganda on its head: memes can be Boschian in this respect, forcing a confrontation with the limits of the false world, and provoking the viewer into self-examination as a precondition for resistance (‘am I too an NPC [non-player-character]?’).

Today conservatives are confronted by a further tension that will undoubtedly come into focus in the near future, and that already is recognisable in the visual culture, between a technophilic, Promethean, transhumanist vision and a conservative urge that cautions against rapid change, whether politically or culturally, and that seeks as part of the never-ending image-struggle to oppose bad images with good and aspirational models that flow from the Imago Dei. We see the former tendency in popular online images such as those often made with AI—under the heading of “archeofuturism,” which combine classical and traditional architectural forms with high-end future-tech in a kind of postmodern picturesque.

The French New Right thinker Guillame Faye, who coined the term, describes it as a kind of “vitalist constructivism” which begins both from the break with philosophies of progress and from the image of a “post-catastrophic world.” Here it is not a matter of conserving (and there’s a whole other conversation to be had about heritage), nor of returning to a recent idealised past, but of “regaining possession of our most archaic roots, which is to say those most suited to the victorious life” and to synthesise these roots with “technological science.” A conservative and Christian defence of the priority of sacred images will have to confront more and more the techno-vitalism of a virtual age. But at least the stakes here are clearer, and opponents more likely to engage in true disagreement rather than censorship and slander.

In this regard, it is worth returning to one of most enigmatic images that the Western tradition has produced, Albrecht Dürer’s 1514 woodcut, Melencolia I. To me, the angel, the aspirational part of ourselves, surrounded by tools, codes, symbols, and measuring devices, is both sad and rueful at once, at once painfully aware and amused by our inability—no matter the hubris—to contend with the act of God’s creation. There’s just no competing with a rainbow, no battle to be had with the sun. And yet we continue to try, with all the humility and good humour this revelation should induce.

Art and culture have found themselves in recent years turned into the propaganda wing of liberalism. They have been characterised by literalism, narrow politicisation, humourlessness, and an ugly bureaucratic spirit both in their funding and execution. There is no choice, however, but to travel through enemy images—not only the dominant images of our enemy which confront us but the images that form a counter-faction of every genre and media that indict us, and that force us to become critics of ourselves, in the first place—and, simultaneously, of our age. An iconophilia oriented to the good and the beautiful has always been possible, if generally occluded by those with a vested interest in destroying our imaginative and spiritual capacities. The image war never ended: but as the old regime crumbles under its own contradictions, and we reembrace representation, as if awakening from a nightmare, let us not forget the power of images—and what they can teach us about the good.

This essay appears in the Winter 2024 issue of The European Conservative, Number 33:12-16.