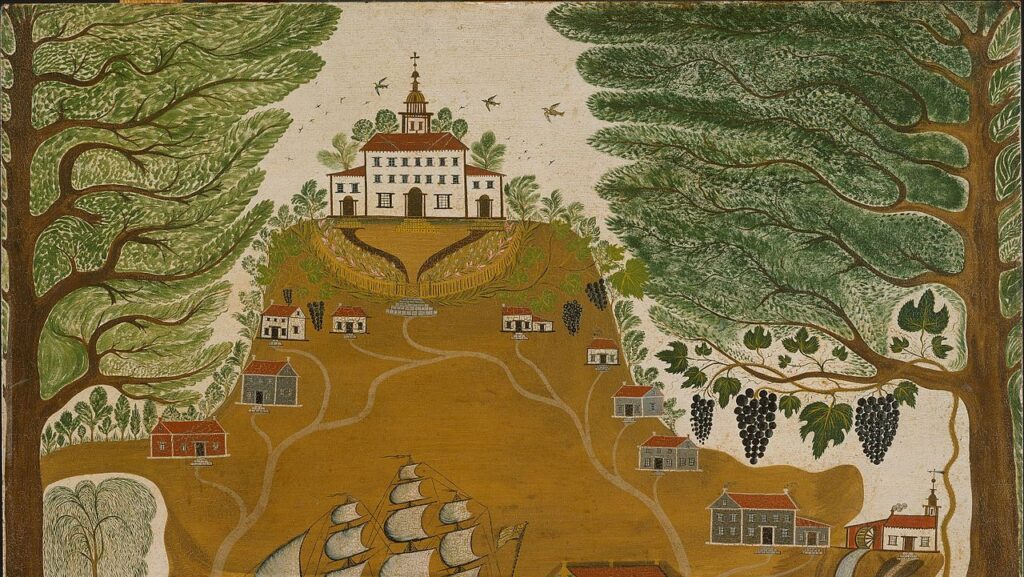

The Plantation (c. 1825), a 48.6 x 74.9 cm oil on panel by an anonymous artist, located at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, New York

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

All human communities have deficits, and thus there have always been people who wanted to split from the majority in order to build a new, ideal society. More often than not, these new communities have failed, as human nature, at least in the long run, seems to be only rarely capable of corresponding to its own ideals. However, some parallel communities have managed to endure and to become the kernel of a new mainstream society. This new series of columns will present a selection of these highly idealistic—but often short-lived—communities, analysing their structure, their flaws, and their development, while also reflecting on their relevance to present-day issues. Some of these communities are well known, although others have been completely forgotten, such as the ‘Vine and Olive Colony’ and the ‘Champ d’Asile,’ which were founded by Napoleonic veterans and refugees in Alabama and Texas.

After the fall of Napoleon’s Empire, a group of Bonapartist veterans and refugees known as the ‘French Emigrant Association,’ and led by General Charles Lallemand, petitioned the U.S. Congress for permission to establish a colony at the confluence of the Black Warrior and Tomigbee Rivers. Permission was granted on 3 March 1817, on the condition that vines and olives be grown there, probably to prevent the colony from devoting itself to paramilitary activities. As early as July 1817, the first 200 settlers—dissidents from France as well as planters who had fled the slave revolt in Saint- Domingue—reached the settlement area of some 373 square kilometres. The first president of the colony was Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes, another former general, who, like so many others, had fled to America in 1815 to escape the Bourbon death sentence.

After a first village called Demopolis had to be vacated as early as 1818 due to a surveying error, the settlers founded three new villages: Aigleville, Arcola, and Marengo (later renamed [Hohen]Linden)—names that clearly refer to the Republican and Bonapartist convictions of the settlers. The settlers initially lived in log cabins with small, attached garden plots and farmland outside. They were gradually supplemented by the arrival of new French and American settlers, especially as lively land speculation soon began.

The colonists soon realised that the allotted land was unsuitable for the cultivation of wine and olives and the desired small-scale farming lifestyle. In 1822, they obtained permission to turn to other activities, especially cotton, with which the settlers from Saint-Domingue in particular had a great deal of experience. The Napoleonic model settlements increasingly became a series of scattered cotton plantations, largely farmed by slaves (among the investors was Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon’s brother). Floods, famine, and conflicts with American settlers ensured that only the largest plantations survived. The colony as such largely disintegrated from 1825 onwards: some veterans returned to France, where Louis XVIII had died only a few years after Napoleon; others resettled to New Orleans; and the remainder quickly merged with Anglo-American newcomers. Aigleville was completely abandoned by the 1830s; Arcola was briefly taken over by American settlers, then also largely dissolved; only Demopolis and Linden still exist today.

But the story does not end there. In 1818, some of the inhabitants of the Alabama Colony—later joined both by other veterans from France and by French-born inhabitants of the U.S.— broke away, under the leadership of General Lallemand, and moved to Texas, which was then a disputed border area. With the permission of Congress, they began to establish Champ d’Asile, a colony not far from Galveston, the base of the local, French-born corsair, Jean Lafitte. To this end, Lallemand wrote a proclamation that was distributed as far as France, in which he advertised for settlers and subscribers and advocated an enlightened romanticism entirely in the spirit of Rousseau. Although his proclamation refrained from making any political statements, it was clearly written in the spirit of modernity and Masonic deism:

Brought together by a series of misfortunes which exiled us from our homes and scattered us abroad in various countries, we are resolved to seek an asylum where we can remember our misfortunes to profit thereby. A great country stretches out before us, uninhabited by civilised man, given over to Indian tribes who do naught but hunt, leaving idle a territory as fertile as extensive. In adversity, far from being subdued in courage, we are exercising the first right given by the Author of Nature, that of settling on this earth, to cultivate it, and draw from it the products which nature never refused to the patient labourer. We are attacking no one, and we have no hostile intentions. … Here it is our desire to live in a free and honourable way or here find our grave.

It was also expressly emphasised that only soldiers of the ‘Grande Armée’ and native Frenchmen should have citizenship. The history of this short-lived colony is described in a brochure (printed in Paris in 1819) by Hartmann, one of the participants, with much pathos but suspiciously few details: political questions, as well as important information known from other contemporary sources, are concealed. A cautious reconstruction would suggest that the entire colony was tightly organised with the settlement protected by four small forts and eight cannons, and the population of around 400 men was divided into four ‘cohorts’ and subjected to strict military organisation. The chronicle of the colony repeatedly describes the disciplined and soldierly simplicity of life, albeit under a thick layer of Rousseauian—even proto-socialist—pathos that suggests the core of the settlers might have been heavily involved not only in the Empire, but also the first Republic:

There was no jealousy, no unworthy ambition among us; corrupting luxury did not tempt us. Our arms were our jewels; our land, homes, and gardens our wealth. The fruits the earth gave us and our farming instruments were all means of diversion. Everything was shared among us; and if sickness happened to strike down one of our brothers, he was given the most prompt relief that solicitude, attention, and aid could afford. Interchange of sympathy, reciprocity of delicate actions, proofs of friendship, interest, and attachment strengthened moment by moment the bonds binding us to each other. Such, in general, are all early societies. Why are they not still in their dawn?

Why had this contingent broken away from the main colony and possibly (at least in demographic terms) fatally weakened the latter? One reason could be Lallemand’s dissatisfaction with the more ‘liberal’ course taken by the Alabama colony, which was rapidly dominated by the cotton planters. Another reason may have been that Champ d’Asile was located in the no man’s land between the U.S. and Mexico, and may have raised hopes of the permanent establishment of a proper state, even more so as this territory had only recently belonged to France. Added to this was the fact that Joseph Bonaparte had also emigrated to the U.S. in 1815 and, as former Spanish king, cultivated excellent relations with revolutionary Latin American circles: in 1820, Mexican revolutionaries were even said to have offered him the crown of their country. It is possible that Champ d’Asile could have formed a certain preparation for such a manoeuvre and therefore explain Lallemand’s astonishing move. Still others speculate that the aim was rather to gather a small army there, in order to liberate Napoleon from St. Helena at the right moment.

Be that as it may, Champ d’Asile was never to fulfil any of these functions. Some settlers drowned in storms; others fell ill and died due to their ignorance of the local flora; the agricultural output was unsatisfying; the hundred slaves that had been bought all managed to escape; and the memoirs show that the colony was populated almost exclusively by men. Soon, the Mexican authorities, still under the Spanish crown, heard of the colony’s existence. They considered it the vanguard of a larger Bonapartist destabilisation plan. A military detachment of around 600 soldiers forced the colonists, ill- equipped and without sufficient food, to retreat to Galveston Island. The island was devastated shortly afterwards by a severe storm, after which the colonists lost most of their possessions to local speculators, much to the indignation of the chronicler:

The vices of civilisation penetrate everywhere; in the heart of cities, in the midst of deserts, and in Texas; as well as on the banks of the Seine, one meets with degraded beings, who, to accumulate a little gold, will speculate on the misfortunes of their fellows.

That was enough for most of the colonists, who then scattered to the four winds.

What lessons can be learnt from the events in Alabama? The most obvious is the danger posed by a lack of economic preparation: while the original model—olives and wine— would have allowed a lifestyle quite similar to the French one, the geographical reality forced a plantation model on the settlers that made a closed smallholder economy impossible. Another problem was the gradual takeover of the land by non-French people—a weakness that Champ d’Asile wanted to correct with a very restrictive citizenship law. Finally, there were the historical conditions: the calming of the situation in France after the death of both Napoleon and Louis XVIII gradually eroded the cement that had originally held the settlers together.

The Texan colony, although shorter-lived, is better documented. Here, the military and patriotic aspect obviously outweighed the economic, and the surviving descriptions illustrate the strong ideological underpinning, which was not only Bonapartist and patriotic in flavour, but apparently drew heavily on Rousseau and early socialists. Economic issues and, most importantly, the general absence of women would have quickly caused serious problems is the political uncertainty in the no-man’s land between the U.S. and Mexico had not brought a military threat onto the scene, against which the settlers proved to be powerless.