Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 is not a nude, as French cultural theorist Paul Virilio points out. It’s a prickly blur. We see no body, but a sequence. Neither is it a sequence as we remember it—the moment when someone looked down from the top of the stairs, their hand resting for a moment on the rail half way down, etc. It is the sequence all in one abstract sweep.

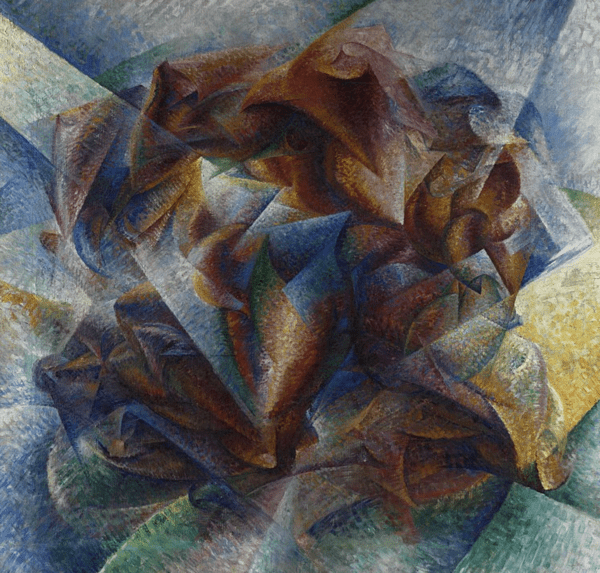

Boccioni’s Dynamism of a Football Player is different. The Calabrian futurist also abstracts the human form, more so than Duchamp, but he takes those fragmented angles and assembles them into something like a sphere. His Dynamism is a single entity with a centre. A football player, usually so directed, is presented in place and yet, in movement. If we were to imagine a martial artist displaying his skill without need for an opponent, it would be something like Boccioni’s vision. Here, dynamism is truly a noun, an entity, rather than a verb. Neither are its many vectors of movement sharp, jagged edges. They are rather like wind-swept fabric.

Paul Virilio, author of Speech and Politics among other works, wrote that “if time is money, speed is power.” We may suggest that the success of a political order (inclusive of the fourth estate) to utilise speed depends on its ability to generate novelty. In order to keep a population’s attention on something, there must be the appearance of consistent objective signals indicating the, preferably escalating, urgency of that issue. News has to be continuously circulated and some measure of bombast is required if desensitisation is to be avoided. The succession of crises in which Schmidt’s state of emergency takes precedence over legally and socially established norms, as observed by Agamben, is precisely relevant here. We find politics requiring momentum, fearful that if it should sit still, it might not be able to get up again (to once more manufacture consent).

Concerning the farther reaches of the damage this political use of speed can have on a population, we may reflect on the appearance which continuous novelty by the roadside takes from inside a speeding car. It tends towards the blur. This is something Paul Virilio notes. For our part, we may relate it to the blurring of human differentiation, to the point that a civilization may so intoxicate itself with the propulsion of “progress” that it feels capable not only of abolishing borders, but even legislating away realities like gender. It no longer sees them—everything is a blur.

With regards to geopolitics, one sense in which “speed is power” is in terms of logistical agility. The ability to transport goods from China to London, for example, produces the impression of a real, permanent presence. The Chinese items stocking shelves are always new, but one can conceive of them as permanent features of one’s shopping cart because they are reliably restocked. The speed and stability of logistics—in this case supply chains—creates presence. China is present in London, because it can quickly and consistently send itself out. The centre from which this sending occurs is only conspicuous when it fails to do so, and shoppers are forced to reflect on that background whose workings they are usually as unaware of as the inner workings of an iPhone.

Speed produces reliance, therefore, and reliance may be understood as a power dynamic if the entity relied upon has access to alternative markets, whereas the dependent one does not. This being the case, it stands to reason that rising powers will seek to inherit not only the material, but also the momentum, of preceding structures. When Jan Huyghen van Linschoten and Cornelis de Houtman discovered Portuguese trade routes, these were taken up by the Dutch East India Company, and as British dominance over global sea trade declined, the Japanese began servicing the Pacific trade routes Britain was abandoning. But delays in this handoff will provide time for alternative trade relationships to be established. Therefore, power vacuums must be momentary; transitions seamless.

An often-overlooked implication of this, is that it is not always political actors who determine the ideological content of world order. The fact that an actor’s power relies on becoming the new guarantor of existing needs will deeply condition that actor’s project. Today, it would be absurd for China, for example, not to insert itself into existing global structures in order to forgo the task of constructing alternative arrangements (except where necessary). What is more interesting, however, is that China is not only maintaining the structure of world order, potentially including a petroleum-pegged currency (at least in the medium term), but also its direction.

The United Nations’ 2030 Agenda is relevant here. It is worth highlighting that this ambitious transformation of the world economy is taking place at the very moment when we seem to be witnessing the definitive decline of U.S. hegemony (although not necessarily prominence). In his opening address to the World Economic Forum on January of this year, the Chinese President Xi Jinping emphasised the importance of that organisation’s various policy priorities, from COVID-19 vaccines and new technologies like 5G to achieving carbon neutrality, but he specifically referred to the need to keep the world economy’s pace from slackening. It must press forward because the alternative is to risk derailment: “If major economies slam on the brakes or take a U-turn in their monetary policies, there would be serious negative spill-overs.” And yet, it is also a force of nature, a historically determined fact, which cannot be stopped:

Economic globalization is the trend of the times. Though counter-currents are sure to exist in a river, none could stop it from flowing to the sea. Driving forces bolster the river’s momentum, and resistance may yet enhance its flow. Despite the counter-currents and dangerous shoals along the way, economic globalization has never and will not veer off course.

This accompanied a familiar lionising of global economic integration as a moral good in terms of floating signifiers like “openness,” “togetherness,” and “vitality:”

We should remove barriers, not erect walls. We should open up, not close off. We should seek integration, not decoupling. This is the way to build an open world economy…to make economic globalization more open, inclusive, balanced, and beneficial for all, and to fully unleash the vitality of the world economy.

To this end, existing structures should remain in place, and those new technologies to which these structures have already committed should continue to be pursued:

We should … uphold the multilateral trading system with the World Trade Organization at its centre. We should make generally acceptable and effective rules for artificial intelligence and digital economy on the basis of full consultation, and create an open, just and non-discriminatory environment for scientific and technological innovation.

These structures ensure global unity:

A common understanding among us is that to turn the world economy from crisis to recovery, it is imperative to strengthen macro-policy coordination. Major economies should see the world as one community, think in a more systematic way, increase policy transparency and information sharing, and coordinate the objectives, intensity and pace of fiscal and monetary policies, so as to prevent the world economy from plummeting again.

China, it seems, is determined to maintain the momentum of current, UN-directed, trends in the world economy in the face of COVID-19 and, we might add, in spite of the possible power transition from U.S. hegemony, of which Xi Jinping’s speech at Davos is an indication. We noted that the Chinese president refers to the dangers both of putting on the brakes and doing a U-turn with respect to current developments in the world.

There is nothing remarkable about this rhetorical emphasis on growth, historical determinism, the virtue of openness, and global unity of action. Again, these articulate the inherent logic of those institutions through which global power manifests, and will therefore be the mainstays of any actor who seeks global prominence principally by making use of such institutions.

We are used to thinking of prevailing power structures as ideologically committed in ways that respond to a specifically western sensibility, but this risks obfuscating the degree to which global initiatives like the 2030 Agenda represent an economic opportunity to create, promote, and establish a priori dominance over new industries—the so-called “fourth industrial revolution.” (Whether associated technologies represent added value from the perspective of human flourishing is an entirely different question—they could likely be used in ways that are edifying, if this use were selective, but we are discussing their projected mass deployment.)

Many of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals are clearly geared towards accomplishing feats of social engineering in conformity with a specific worldview, but the stark economic opportunity of 5G roll-out, Internet of Things, or self-driving vehicles is an incentive unto itself. If we were to attempt a neutral assessment of the impact which the mass application of these technologies to a host of everyday activities is likely to have (whether helmed on the world stage by Biden or Xi Jinping), we might refer to the radical expansion of surveillance and data gathering capacities, or—more subtly—to an atrophying of relational and reflective human faculties.

Additionally, it may be suggested that specific elements of western postmodernity (such as sexual libertinage or the appeal to mass migration as an exercise in collective charity and historical justice) transcend the genealogy of ideas that gave rise to them, having value as technologies of social control, given specific conditions. It doesn’t matter that the West’s more eccentric innovations in deconstructing tradition were arrived at through a specifically western intellectual current—if they help atomize society and increase state or corporate control, there will be an incentive for them to get picked up by elites in very different cultural spheres.

This being the case, we can imagine their surviving the political elites that currently champion them, and being tactically deployed by some rival elite. Besides this, the blurring of human categories may be intrinsic to the use of sensorily-overburdening novelty-generating technology in mass media (‘internet-addicted Zoomer-brain’), and therefore to the power these allow their wielders to exert on a population.

The question posed by the above is how to bring politics, or the deliberate exercise of virtue-ethics at the collective level, back into world affairs, be it by 1) interrupting present momentum without inflicting those “negative spill-overs” Xi Jinping warns of upon vulnerable populations, or 2) making selective use of existing momentum in ways that might ultimately transform it.

If we return to our futurist portrait of a football player, the key here may be to ensure that dynamism (rather than distortion) acts like a veil for an entity that is clearly located, resembling Boccioni’s fabric-like curves around a centre, rather than merging together forms on a spectrum. This is likely inseparable from the rejection of growth and innovation as portals through which we might receive a vision of the good—it will not come in the blurring image of space curving around us, but in perfecting a dynamism that’s fixed in place. We will have to determine how technology might best be integrated into a clearly defined sense of social health. Alternative structures conforming to such an ethos, providing resilient local production and supply chains, will have to be established so that changes in global trade do not hurt communities.

In international relations, this may translate into the emergence of blocks of countries in whose interest it is to “change gears” on globalisation, as Ha-Joon Chang puts it,

The biggest myth about globalization is that it is a process driven by technological progress …. However, if technology is what determines the degree of globalization, how can you explain that the world was far more globalized in the late 19th and the early 20th century than in the mid-20th century? … Technology only sets the outer boundary of globalization … It is economic policy (or politics, if you like) that determines exactly how much globalization is achieved in what areas.

There are, of course, very clear positive pressures in this context. Recent crises around the COVID-19 pandemic and medical equipment shortages, or the vulnerability of Europe’s energy supply on account of the war in Ukraine, may lead governments to favour a shortening of supply chains and moving in the direction of relative autarky. This would compromise the architecture of existing world-order and the ability of any world-power to profit and exert influence through it, which is why China was trying to dissuade policy-makers from that option at the World Economic Forum. Conversely, however, it could lead towards an economically sturdier version of what we already have.

Positive developments could be served by the attractiveness of explicit ideological commitments in the face of technocratic appeals to the neutral good of progress, the galvanising power of rebellion against the power dynamics those appeals conceal, and the soft-power exerted by a culture that disengages from the ever-increasing speed of politics. For now, however, we should be clear that this sort of alternative, if it is on the horizon, has yet to arrive on the stage of world affairs.