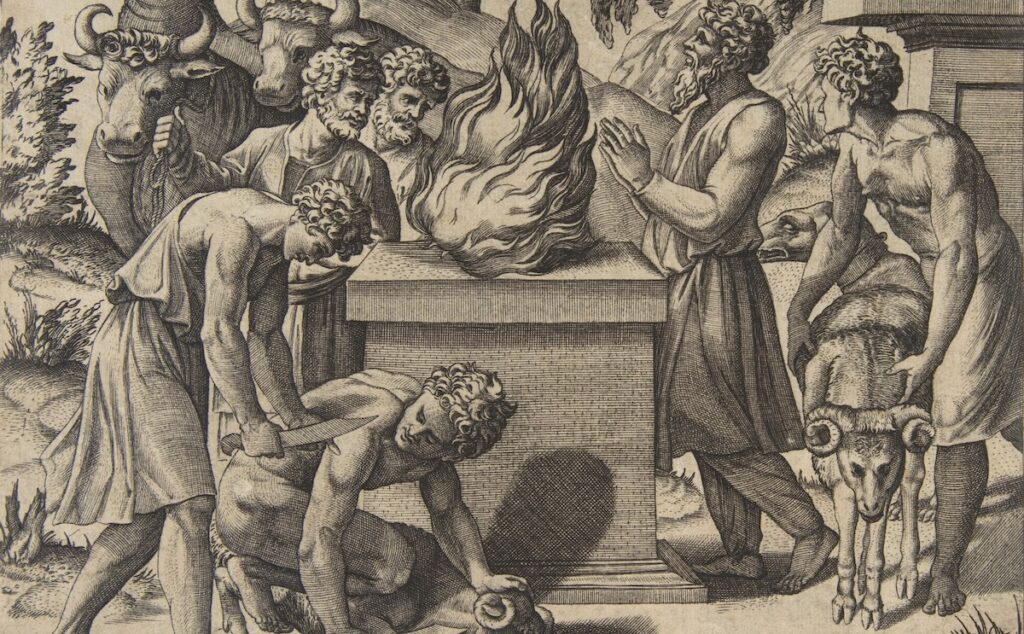

“Noah’s Sacrifice” (1515–27), a 20.4 × 23.9 cm engraving by Marco Dente after Raphael.

The idea of sacrifice has always haunted the human mind. From our earliest days, every society has engaged in deliberate, ritualistic offerings of something dear to its members in order to gain their deities’ blessings. This concept—mystical, often violent and obscure, but also intuitively vital—has many faces and thus remains elusive. What is sacrifice? What role does it play in our mythical thinking? What is its purpose? Is there still a place for it in the modern world? These are but a few questions surrounding these rites.

There are two principal ways to understand sacrifice. The first and more ancient meaning of sacrifice involves a gift to the divine. This meaning is considered mainly by students of anthropology, history, and religious studies. The second meaning belongs to the domain of moral philosophy and concerns the individual’s decision to put his interests aside in the name of a greater good as defined by his own values and principles.

The two are closely connected; indeed, in many myths, a hero or a deity makes a ritualistic sacrifice to a third party (or even to itself in another form) for a higher cause. Christianity provides the most obvious example, Jesus Christ being both a deity and a sacrifice. Alternatively, a man who follows his heart by making a sacrifice may do so based on the ideals he holds sacred. Yet there are also many cases when there is a clear distinction between the types.

There are several theories about the origin of the idea. Each of these focuses on a particular aspect of the notion. The first is that a sacrifice functioned as a gift to a deity, and was an attempt to establish a bond, secured by a subsequent cycle of gifts, with offerings being reliably exchanged for safety and prosperity. This was, and in some cases, remains, a common practice in most religions of the world; from Aztec human sacrifice to Huitzilopochtli, the sun god battling against darkness, to the sacrifice of vegetables that still exists in Hinduism.

The second theory about sacrifice also suggests an attempt at connection, not just between a man and a god, but also between members of a community; this is often the case if the sacrifice is consumed by those who make it. Killing and eating of a totem animal is a good illustration of such a ritual.

The third concerns a deity itself being sacrificed through a person or an animal representing it, often as a means of rebirth or rejuvenation; alternatively, it represents the destruction of weaknesses or sins, symbolically laid upon the victim. The term ‘scapegoat,’ for example, originates from the ancient Jewish ritual of sending a goat symbolically loaded with the community’s sins into the wilderness. There are other theories, including the economic theory, which links the type of sacrifice with the available resources; the Freudian theory based around the Oedipus complex; and the recreation of a mythical event.

What unites all kinds of religious sacrifice—and the word ‘religious’ here encompasses not just traditional faith but also the secular systems built around ideas that substitute for gods—is that it expects an acknowledgement. Mythical thinking views sacrifice as a conjunction of the worldly and the divine, a way of communication and transformation; proper ritual is, therefore, crucial to it. As Moshe Halbertal, a visiting professor at several Ivy League universities, writes in his book On Sacrifice, “[r]itual is thus a protocol that protects from the risk of rejection.” It may be viewed as a safe method of approaching a higher being or a magical binding that, if performed correctly, ensures success. A ritual may also emphasise the deliberate nature of the sacrifice and its importance; it is a powerful tool that provokes an emotional response.

It is also common for sacrifice to be associated with violence, and not unreasonably, since violence is a powerful legitimising factor. It is easy to agree to experience pleasure; but acceptance of pain, either suffered or inflicted, is proof of conviction and a sign of the importance of the moment. The significance of the violence increases if the victim is innocent—as the victim often is in a sacrifice, since sacrifice is about giving something away and not about meting out just punishment. The brutality of the experience may vary, from short symbolic fasting or loss of a small portion of wealth to actual blood and death.

All this is relevant to the first kind of sacrifice: religious. Moral sacrifice, on the other hand, is based on a principle rather than an acknowledgement or an attempt to build a relationship. Self-interest and potential gain are of no consequence to it. There is also no need for ritual, since moral sacrifice is a complete act in itself rather than an attempt to establish a connection. The two types are not mutually exclusive: martyrs, for example, enter a grey area where deity merges with principle. At the same time, if religious faith is involved, the martyr typically believes that he will be rewarded for his loyalty in the afterlife, while the only personal gain a secular martyr hopes for is the survival of his legacy.

A moral sacrifice is ultimately an act of self-denial that expects nothing in return. Even the gratification one might feel as a result is only a by-product, not a primary purpose. However, as Halbertal points out, the self-transcendent nature of moral sacrifice does not necessarily make it morally right. He notes that crimes committed for a higher cause are often far greater than those committed for personal gain; a murder may be motivated by greed or passion, but a genocide requires an idea. The nobility of a sacrifice depends on what it was made for, and not the other way around.

Yet it also should be remembered that different cultures may have very different opinions about what is considered noble, desirable, and worthy of defending. To those who share the ideals it was made for, sacrifice serves as a source of inspiration (or righteous anger if its circumstances were tragic rather than glorious) and cohesion. Such a moral sacrifice may galvanise society and push it to achieving the ideal it glorifies. The sacrifice takes that ideal and makes it intuitively understandable to everyone. And even after the ideal is achieved, some of these sacrifices live on in the memory of many generations, transforming into legend, forging traditions, and contributing to the creation of an ethos.

War is always particularly rich with the stories of sacrifice, both moral and religious, and unsurprisingly so. It is a time of intense passions, radical views, and ever-present fears, a time when the future is uncertain, the law is often silent, and death is no longer a distant possibility. But it is also a time of opportunity, if one is willing to take it. As it has been said many times, war tends to bring out the best and the worst in people; some murder and pillage indiscriminately, while others fight honourably and give away all they can spare. War also breeds propaganda, an artificial and vastly powerful amplifier that provides guidance for the nation’s fervour—and perfectly utilises the impact of sacrifice. In fact, propaganda is often responsible for creating myths, especially if reality lacks the necessary dramatic structure.

An example of an inspirational sacrifice is the death of Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, who died valiantly at the very moment of his triumphant victory in one of history’s most famous naval battles. Nelson was already a hero to admire, and his words upon receiving his mortal wound enhance this heroic image further: “Thank God I have done my duty.” Lord Nelson became a legend of the Royal Navy; however, because he risked his life willingly in service of a higher cause, his death caused sorrow but not rage.

As an example of an innocent victim who suffers terrible injustice and becomes a symbolic representation of virtue and suffers terribly, we can turn to the Indian Mutiny of 1857. In a town called Cawnpore, the rebels broke the terms guaranteeing the safe evacuation of the garrison. They took prisoners and executed them; more importantly, they captured and later butchered around 200 European women and children. The British public was horrified and infuriated by the massacre, which led to retribution on a massive scale.

Major-General Charles George Gordon defended Khartoum in 1884-1885 during the Mahdi uprising. The situation he found himself in was entirely his own doing, as he conducted his campaign in Sudan according to his view of Britain’s interests but against government orders. The government was reluctant to help him and only sent a relief force due to public pressure. It arrived too late: General Gordon was killed, along with his men and countless civilians. His death was certainly heroic, yet the nation also felt he was betrayed—a sentiment shared by many officers, notably General Wolseley, the relief force commander. The scandal cost the government its office, and though years had passed before another expedition to Sudan was launched, General Gordon was ultimately avenged.

All this is as relevant today as it was two centuries ago, because in every society, in every time, we tell each other the same stories and assign them the same meanings. Acceptable forms of sacrifice may change, especially within the realm of religion, but its essence remains. It is based on the deeply rooted sense of something larger, more important than oneself: a deity, a family, a nation, or the entire world.

Modern man, obsessed with asserting his uniqueness and seeking pleasure, still instinctively wishes to be a part of a community. However, he is unsure what to make of sacrifice. Contemporary philosophers echo these doubts; Johannes Zachhuber, professor of historical and systematic theology at the University of Oxford, offers the following description of “somewhat conflicting” current approaches to the concept:

[O]n the one hand, there is a critical view for which sacrifice is associated with violence and, therefore, cruelty. Sacrifice is the wasteful loss of human life for a supposed gain in some public good. … The other strand in contemporary references to sacrifice is focused more on the potential loss of communal cohesion that is indicated by the receding willingness of individuals to give up something precious to them for the good of the group. Sacrifice is encouraged or even demanded as a symbol of people’s commitment to their class or nation, as a token for the person’s awareness of the value they gain from their integration into a functioning social whole.

Rediscovery of the importance of sacrifice may save Western civilisation. There is more to life than comfort; there is duty, honour, knowledge, love, and beauty, all of which have a price. Our ancestors have worked, created, fought, and bled to leave us the best possible inheritance. The world was theirs, and they gave it to us, at great cost. It is our obligation to do the same for our children.