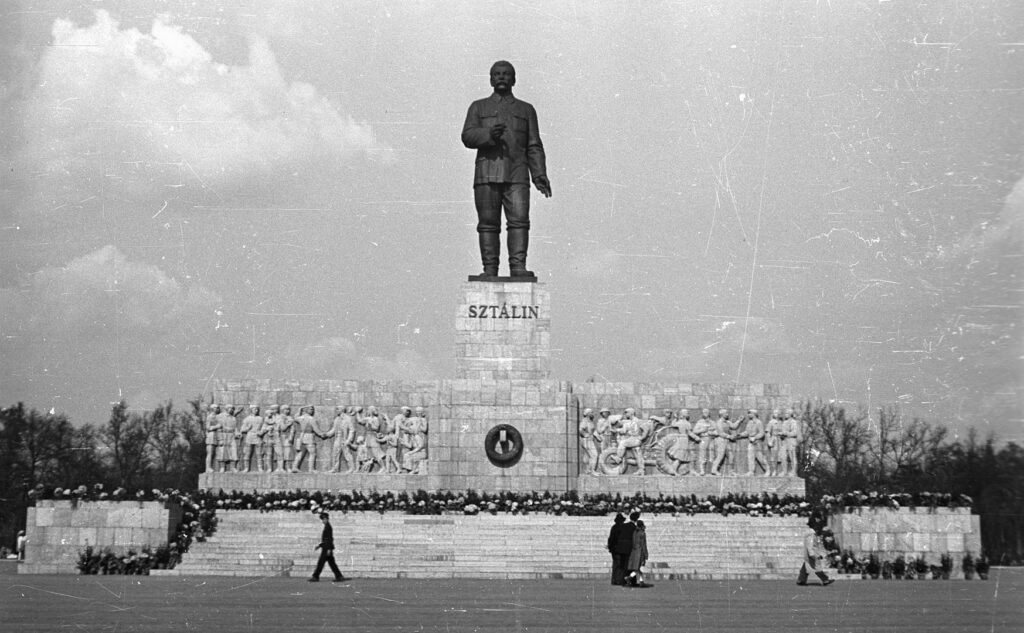

The Stalin Monument was a statue of Joseph Stalin in Budapest, Hungary. Completed in December 1951 as a gift to Joseph Stalin from the Hungarians on his seventieth birthday, it was torn down on October 23, 1956 by enraged anti-Soviet crowds during Hungary’s October Revolution. Its destruction has been called one of the most spectacular events of the 1956 Revolution.

“The trick, William Potter, is not minding that it hurts.”

One wonders if Lawrence of Arabia’s screenwriters, both communist sympathizers, were thinking of Arthur Koestler when they wrote Lawrence’s bravura line about putting out a match with his fingers . Although Koestler was persona non grata on the Left for breaking ranks with the Communist Party, his novel Darkness at Noon sold millions of copies in the 1950s, exposing the sham of communist show trials through the brutal ordeal of Rubashov, an Old Bolshevik who is forced to confess to an invented conspiracy. While stewing in his cell, Rubashov steels himself for interrogation by burning his hand.

The screenwriters would not have been the only authors inspired by Rubashov’s fate. John le Carré, the patron saint of Cold War ambiguity, is about as far from Koestler, the brazen and occasionally didactic anti-communist polemicist, as you can get. His characters operate in the moral gray zones of professional espionage, sacrificing agents and compromising principles without much thought. In le Carré’s world, competition among Eastern and Western spy agencies, though occasionally violent, is a professional rather than an ideological affair. Moscow Centre, “The Circus” in London, and the American “cousins” may as well be fighting for shares in the mail-order mattress market.

Yet MI-6 agent Alec Leamas, the leading man of le Carré’s The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, thinks of Rubashov’s burned hand when facing interrogation on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain. Leamas is defiantly apolitical, a seasoned practitioner of spycraft who cares nothing for ideology or politics. However, the reference to Rubashov is quite suggestive. Just as the climax of The Spy Who Came in From the Cold reveals Leamas’ sound moral instincts, the allusion to Darkness at Noon suggests that le Carré was quietly influenced by Koestler’s critique of Marxism’s crude utilitarian logic.

Darkness at Noon grapples with the dilemma articulated by Rubashov, a former high-ranking party official who is forced to confront the morality of sacrificing one individual for an amorphous greater good. Leamas, the veteran British operative at the center of The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, is faced with a similar question: when is it permissible to sacrifice one man for the sake of an intelligence operation?

Rubashov had made these sacrifices his entire career. Indeed, his false confession is prompted not by physical torture but by the remorseless logic of consequentialism—he must give himself up for the sake of the party, the only vehicle for mankind’s salvation. Whatever crimes may be committed, however many individuals sacrificed, all are justified by the ultimate outcome: the victory of revolutionary Marxism and the establishment of a proletarian utopia.

On the other side of the Cold War, Leamas becomes an unwitting but vital cog in a British covert operation premised on the same brutal logic. He thinks he’s being sent behind the Iron Curtain to eliminate Mundt, a vicious East German intelligence officer and former Nazi responsible for the deaths of several British agents. Only later does Leamas realize that Mundt, far from being the target of the operation, is actually a vital MI-6 asset. To throw East German counter-intelligence off the scent, London falsely implicates a true-believing communist while placing Leamas (and his innocent girlfriend) in the crosshairs.

Both Le Carré and Koestler grasped the intellectual appeal of Marxism, which reduces complex moral questions to a simple matter of accounting. Add up the costs of a given policy and weigh them against the promised benefits and everything from the treatment of suspected counter-revolutionaries to collective agriculture to submarine construction can be solved as quickly and as easily as a math exercise. The abstract nature of this crude calculus serves to obscure the human costs, and the resulting proof always demands absolute party loyalty. For by promising utopia, Marxist intellectuals rigged the equation in advance.

The sad irony is that in both books, it is often the true-believing Marxists who are sacrificed on the altar of ‘the greater good.’ As he stews in his cell, Rubashov recalls episodes from his long revolutionary career in which he abandoned or denounced loyal comrades. His friend and first interrogator, Ivanov, persuades him that he must confess for the sake of their shared ideological beliefs. Shortly thereafter, Ivanov is shot for expressing counter-revolutionary sentiments.

In The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, MI-6 chooses Fiedler, a committed communist, as the patsy to be falsely implicated in place of Mundt, the vicious ex-Nazi who is passing intelligence to the West. Leamas and his girlfriend are, in the parlance of modern intelligence operations, “collateral damage.” The shadow war against the Eastern Bloc has made Western intelligence agencies as cruel and unfeeling as their communist counterparts. “Nobody can rule guiltlessly” was one of the epigraphs chosen by Koestler for Darkness at Noon. MI-6 would surely agree.

Sitting alone in his cell, Rubashov gradually realizes that logic untethered from morality is a frightening thing. “He had held to the rules of logical calculation,” Rubashov thinks to himself. “He had burnt the remains of the old, illogical morality from his consciousness with the acid of reason.” Faced with the prospect of torture and execution, the Old Bolshevik finally decides that “perhaps it was not suitable for a man to think every thought to its logical conclusion.”

It is telling that the most ruthless characters in both books are children of the revolution. Mundt was trained by the Nazis before seamlessly transferring his loyalty to the new regime. After Ivanov, the first of Koestler’s interrogators, is shot, he is replaced by Gletkin, a much younger party member who remembers nothing of life before communism. He proudly informs Rubashov that he is completely unmoved by “bourgeois morality,” caring only for the party and its teachings. Old Bolsheviks like Rubashov and Ivanov still experienced occasional pangs of conscience. Gletkin has no conscience to appeal to.

Koeslter and Le Carré shared a revulsion of the crude, mechanical logic of 20th-century ideologies. Le Carré is often accused of Cold War moral equivalency, but he had few illusions about life behind the Iron Curtain. Leamas’ girlfriend, a faithful but naive member of the British Communist Party, is shocked by the realities of actually existing socialism in East Germany.

The specter of communism, the West’s great ideological foe for much of the 20th century, has receded since Koestler and Le Carré were at their creative peaks. Koestler, a refugee from pre-World War Two Mitteleuropa, killed himself in 1984. When the Soviet Union collapsed, Le Carré lost his muse. Yet misguided appeals to utilitarianism and consequentialist logic have outlived orthodox Marxism. Highbrow justifications for brutality and fraud will always find an audience among the intellectual class.

The ‘scientific’ methods of Rubashov’s captors recall the Bush-era War on Terror, which made liberal use of the euphemism “enhanced interrogation” to mask the brutal means by which information was extracted from black-site detainees. At one point during Rubashov’s interrogation, Gletkin blandly states that the Soviet legal system is scrupulous in its adherence to procedural niceties. How many White House lawyers have made similar assurances?

Draconian COVID zero policies persist in authoritarian states like China, but at the height of the pandemic, even liberal democratic Austria briefly implemented a cordon sanitaire to separate the vaccinated from the unvaccinated. Other putatively liberal countries embraced—or at least considered—similar policies in the name of saving lives. While exercising outdoors, Rubashov briefly speaks to an imprisoned peasant from a far-flung province. His crime? “I was unmasked as a reactionary by the pricking of the children,” explains the peasant. “This year, [the government] sent little glass pipes with needles, to prick the children. There was a woman in man’s trousers; she wanted to prick all the children one after the other. When she came to my house, I and my wife barred the door and unmasked ourselves as reactionaries.”

A recent episode of financial chicanery was also camouflaged by hollow humanitarianism. Sam Bankman-Fried, the now-notorious founder of the FTX cryptocurrency exchange, often boasted about his commitment to ‘effective altruism,’ a movement that seeks to maximize charitable giving through the application of utilitarian principles. In practice, Bankman-Fried’s ethical pretensions served as an excuse for the fraudulent acquisition of massive personal wealth. Naturally, investors and journalists alike lapped it up. “The FTX competitive advantage,” according to one credulous investor profile? “Ethical behavior. SBF is a Peter Singer–inspired utilitarian … He’s an ethical maximalist in an industry that’s overwhelmingly populated with ethical minimalists.”

“Ethical maximalism” would have fit seamlessly into the ideological lexicon of mid-20th century communism. At a time when many intellectuals were lulled into complacency, Le Carré and Koestler saw through the crude justifications for torture, mass murder, and human sacrifice. Both authors understood that means cannot be separated from ends, and that crudely tallying up lives saved and lost is a bad way to do business, particularly when the “lives saved” column is skewed by those in power. Despite their stylistic differences, the master spy novelist and the anti-communist firebrand were apostles of a more humane, less mechanistic vision of society.