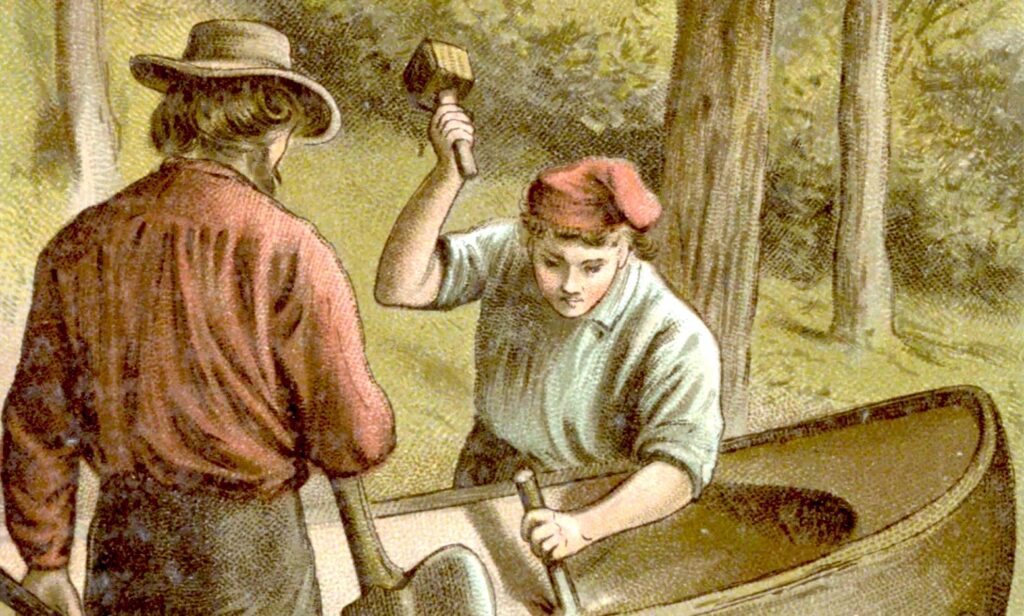

Illustration of the father and son constructing a canoe from The Swiss Family Robinson by Johann David Wyss.

For decades, the great literary scholar Anthony Esolen has been urging people to return to the classics. The canon of literature produced by Christendom may have been largely abandoned, but is still widely available to anyone seeking to claim their rightful inheritance. These books, Esolen once noted, “are the great unused artillery of the culture wars.” One of those much-needed classics was penned by a Reformed rector to teach his sons the virtues of self-reliance and moral character and the practices of family prayer, family worship, and keeping the Lord’s Day—practices in desperate need of revival. Johann Wyss’s adventure story would become one of the most popular books of all time.

The German first edition of The Swiss Family Robinson was published in 1812 to immediate acclaim. The story of a Swiss couple and their four sons shipwrecked on an exotic island on their way to Port Jackson, Australia in a vicious storm and their many subsequent adventures was promptly translated into English in 1814 and French in 1816. The great novelist Jules Verne was so obsessed with the novel that he wrote two sequels, Their Island Home and The Castaways of the Flag, published in 1900; the most recent attempt at a sequel was published over a century later in 2015. To date, more than 200 English versions of The Swiss Family Robinson have been published.

Even though The Swiss Family Robinson has remained wildly popular for generations and spawned several films and countless abridged editions, we know surprisingly little about its author, Johann David Wyss (1743-1818). He was born and died in Bern, Switzerland, and as a young adult he served as a military chaplain in Italy. He gained a reputation as a skilled linguist (speaking four languages) and would eventually become the rector of Bern’s great Reformed Protestant Cathedral. He was a devoted family man who enjoyed hiking, hunting, fishing, and engaging in amateur naturalism with his four sons. He and his wife also enjoyed reading and discussing books with the family—including adventure stories.

One of those books was Daniel Defoe’s great 1719 novel Robinson Crusoe, and Wyss decided he wanted to write a story that would be both adventurous and instructive for his own children. The story models good husbandry and farming, the importance of physical fitness and self-reliance—as Mr. Robinson notes while observing his boys at their exercises: “No man can be really courageous and self-reliant without an inward consciousness of physical power and capability.” Strength and agility were necessary on an island so filled with strange creatures—the story is filled with detailed descriptions of flora and fauna. Even the quagga, a subspecies of plains zebra hunted to extinction within seven decades of the book’s publication, is mentioned.

The book, fittingly, was a family project. Wyss had his sons take turns telling stories and wrote them down. Eventually these were turned into a book, with unpublished illustrations provided by his son Johann Emmanuel. His son Johann Rudolf, who later penned the Swiss national anthem, edited and submitted it for publication. Johann Rudolf returned to the book and published a longer version in 1827. The Robinson family was clearly modelled after Wyss’s own, with the discussions of nature and wildlife reflecting the family’s own interests. Wyss wanted to use an adventure story to teach young readers both virtue and natural history, and the sheer variety of species he placed on a single island was both geographically impossible but educationally convenient.

For the post-Christian youth of today, this story is written in something approaching a foreign language. The Swiss Family Robinson, like so many great literary works of its time, is rooted in presuppositions—that God exists, that He hears people, and that Christianity is true. It begins with the father offering up a fervent prayer for deliverance as their ship is battered by a storm, and prayer is central throughout the book. The Robinsons prayed like they breathed—it was an essential part of how they lived. Prayer was both spontaneous and deliberate; formal and informal.

The first morning after the family is stranded, for example, the father reminds them that before they go exploring, they must bend their knees in morning prayer. “We are only too ready, amid the cares and pleasures of this life, to forget the God to whom we owe all things,” he observes. Every night, the family closes with devotions. When Mr. Robinson struggles with their plight, he “would not communicate the sense of depression to my family, but, turning in prayer to the Almighty Father, laid my trouble before Him, with never-failing renewal of strength and hope.”

In addition to prayer, Johann Wyss emphasized the centrality of the Sabbath. A short time after the shipwreck, Mr. Robinson reminds his family that they must choose a day of rest:

“‘Six days shalt thou labor and do all that thou hast to do, but on the seventh, thou shalt do no manner of work.’ This is the seventh day,” I replied, “on it, therefore, let us rest.”

“What, is it really Sunday?” asked Jack; “how jolly! oh, I won’t do any work; but I’ll take a bow and arrow and shoot, and we’ll climb about the tree and have fun all day.”

“That is not resting,” said I, “that is not the way you are accustomed to spend the Lord’s day.”

“No! but then we can’t go to church here, and there is nothing else to do.”

“We can worship here as well as at home,” said I.

“But there is no church, no clergyman, and no organ,” said Franz.

“The leafy shade of this great tree is far more beautiful than any church,” I said; “there will we worship our Creator. Come, boys, down with you: turn our dining hall into a breakfast room.”

The children, one by one, slipped down the ladder.

“My dear Elizabeth,” said I, “this morning we will devote to the service of the Lord, and by means of a parable, I will endeavor to give the children some serious thoughts; but, without books, or the possibility of any of the usual Sunday occupations, we cannot keep them quiet the whole day; afterward, therefore, I shall allow them to pursue any innocent recreation they choose, and in the cool of the evening we will take a walk.”

The Christian concepts of virtue promoted by Wyss throughout the story are so profoundly counter-cultural that they are almost inaccessible to recent generations. Jokes that involve deceit are reproved. The slightest selfishness earns stern rebuke from the father. When Fritz expresses his indifference to the plight of the sailors who had abandoned them, his father chides him that “we should not return evil for evil.” As in most of the great classics, the essential nature of gratitude in difficult circumstances is constantly emphasized, along with frequent references to submission to God’s will.

At several points in the story, Wyss even grapples with bigger questions, such as when Ernest notes that it is “curious” that “God should create hurtful animals.” His father replies:

To our feeble and narrow vision many of the ways of the Infinite and Eternal Mind are incomprehensible. What our limited reason cannot grasp, let us be content to acknowledge as the workings of Almighty power and wisdom, and thankfully trust in that ‘Rock,’ which, were it not higher than we, would afford no sense of security to the immortal soul.

Wyss assumed that his readers would be familiar with Scripture—his reference to the “Rock” is taken from Psalm 61:2: “From the end of the earth will I cry unto thee, when my heart is overwhelmed: lead me to the rock that is higher than I.” The story is soaked with Scripture. He notes that the family fully realizes the truth of Genesis 3:19: “In the sweat of they face shalt thou eat bread.” After ten years on the island, Mr. Robinson reflects on their story with the words of King David in Psalm 90:9: “We spend our years as a tale that is told.”

More than two centuries after the publication of The Swiss Family Robinson, we inhabit a profoundly different world. Mere decades ago, most Westerners would at least understand many of the biblical references and be familiar with the historical context necessary to understand concepts like the Lord’s Day and the Christian virtues being promoted even if they personally rejected them. The fact that so few find these things familiar today makes Wyss’s work more important than ever.