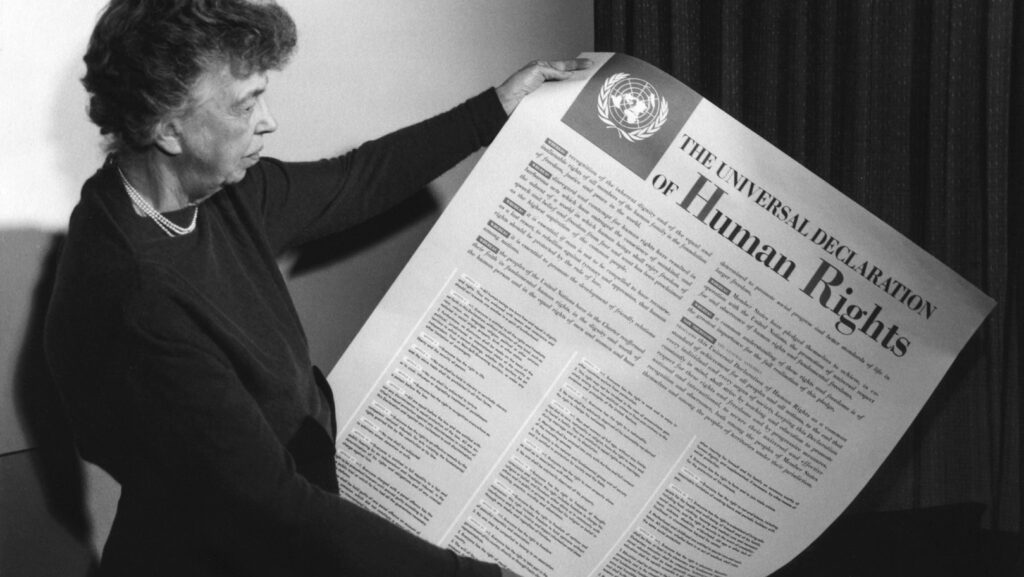

A photograph taken in November 1949 showing Eleanor Roosevelt (1884-1962) with a poster of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which she helped to draft, along with jurist René Cassin (1887- 1976), former member of France’s Council of State and recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1968, and Canadian legal scholar and jurist John Peters Humphrey. Roosevelt was the first chairman of the preliminary UN Commission on Human Rights established in April 1946, and remained chairman after it became a permanent boondoggle in January 1947. Image courtesy of FDR Presidential Library and Museum.

On 10 December 1948, the United Nations General Assembly ratified the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

The very opening words of its Preamble state that “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.”

But unlike the—to my mind—significantly more powerful American Declaration of Independence, which clearly affirms that man’s rights are endowed by his Creator, the UDHR simply assumes that members of the human family have “inherent dignity” with “inalienable rights”—without ever elaborating where that dignity comes from.

For a charter on human rights—for any such charter, in fact—this is more than just a diplomatic omission. It is an extremely dangerous exercise in legal positivism.

The American Founding Fathers were more than aware of the significance of their actions. That is why they were sure to found their new nation on the recognition that certain rights were inalienable (or literally, ‘unalienable’), endowed by God in man’s nature. Man then forms government in order, among other things, to protect those natural rights.

The point about inalienability is essential here—man’s rights cannot be alienated. The Founding Fathers believed that man could never relinquish his God-given rights to the State, even assuming he wanted to do so. Even if the Declaration of Independence had never been promulgated, the Founders believed those rights would have still existed just as surely—because God himself had endowed them.

The Declaration of Independence therefore—and this idea is in many ways just as revolutionary today as it was in 1776—simply recognised pre-existing rights. It did not claim to have created them. Indeed, neither the Declaration of Independence nor the 1787 Constitution ever goes so far as to suggest that it is itself the legal source of such rights.

The UDHR sadly follows in the French philosophical tradition of the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen—which, having learned nothing from the Americans, inaugurated a tradition that has remained in ignorance through to 1948 and down to the present day.

The French model—in contrast to its earlier American counterpart—is a brazen attempt on the part of the state to concede to its citizens their rights by fiat.

The danger is obvious, even if few in power ever acknowledge it.

Because if the state is the author of our rights and has the power to grant them to us, then it has equally the same power to withdraw them from us. The state may call them ‘rights’ but what they would be are not rights, but permissions—provisional permissions that the state could revoke at any moment.

The word ‘rights’ may be the same, but the two realities could not be more different.

It was explicitly in order to correct this imbalance that a number of Members of the European Parliament—led by Gay Mitchell MEP and Nirj Deva MEP—got together and released the text of the Universal Declaration of Human Dignity (UDHD) on 8 December 2008, to coincide with the then 60th anniversary celebrations of the UDHR (and the Feast of the Immaculate Conception).

Read the Universal Declaration of Human Dignity here.

The UDHD was subsequently officially launched by the (then) Speaker of the European Parliament Hans-Geert Pöttering MEP on March 25th, 2009—on which occasion Gay Mitchell and I launched the European Parliament’s Working Group on Human Dignity, which was created to diffuse the values of the UDHD in the European Parliament, and Nirj Deva and I launched the Dignitatis Humanae Institute, which was created to diffuse the UDHD. Similar working groups on human dignity, all drawing inspiration from the UDHD, were launched in the UK, Lithuania and Romania.

I am quite sure about one thing. The imago Dei anthropology is the great unacknowledged pillar of Western civilisation. Man is made in the image and likeness of God. This is stated in Chapter One of Genesis—and is thus literally the foundational anthropology of the Judeo-Christian West.

It is that image and likeness of God which radiates outwards from every single human person that is the source of the very dignity that Eleanor Roosevelt bore witness to—but failed to source—in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 75 years ago this December.

I define ‘modernism’ as the attempt of a post-Christian civilisation to maintain the liberal values that arose out of two millennia of lived Christian experience, while shifting the foundation of those values from divine revelation to secular reason. If you believe in Jesus Christ, you will already know such an experiment is destined to fail. If you do not believe in Jesus Christ but do believe in a liberal society—how is that experiment working out for you?!

This essay appears in the Winter 2024 edition of The European Conservative, Number 29:24-25.