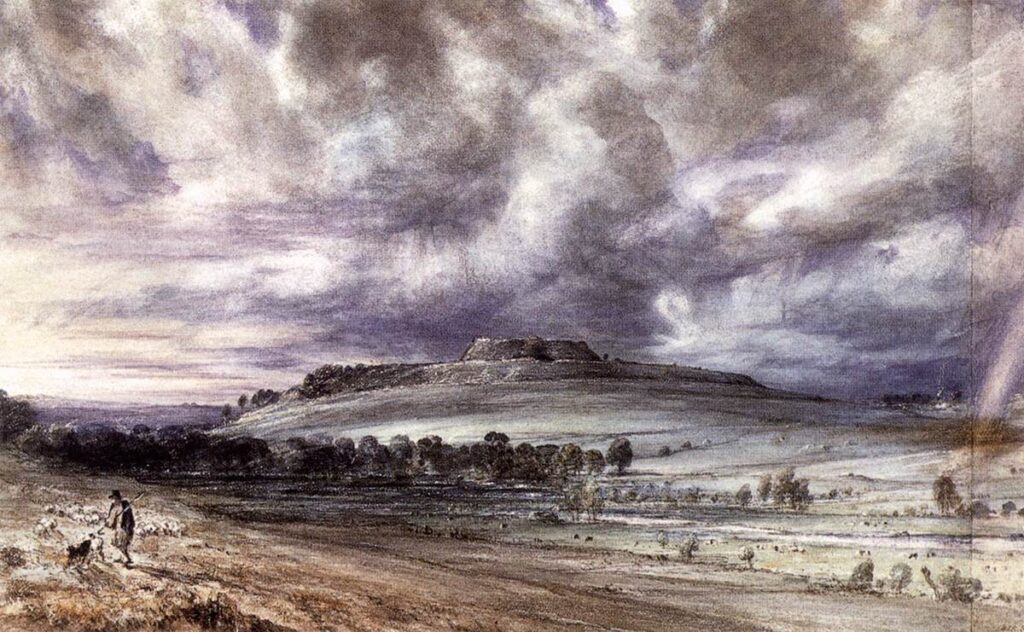

“Old Sarum” (1834), a 30 x 48.7 cm watercolor on paper by John Constable (1776-1837).

“There is nothing so beautiful, lovable and moving as the English countryside,” wrote Stendhal in his novel The Red and the Black, published in 1830. It is hard to disagree with this sentiment, not least since precious shards of history are often found among quiet villages and green hills; the charm and character of the nation are alive there, while the cities, busy and increasingly multicultural, have all but lost their roots.

It is no wonder that the countryside and small towns have always remained a bastion of traditionalism, naturally suspicious of progress and resistant to change. New trends were slower to reach them, while the close connection between the members of a community ensured the passing of ideas and values from parents to children, as well as adherence to the established rules and customs. Cities rushed forward, chasing the bright idea of progress, while towns, farms, and cottages cautiously peered into the future, serving as a reliable anchor that defended the state from imprudent innovations. Such an arrangement has ensured a healthy balance, avoiding stagnation or risking its integrity.

At the heart of this balance were the competing interests of influential groups; in Britain, it often manifested as the battle between the great landed aristocracy—often including the church—and the commercial elite. The former had an intrinsic connection with their domain and were naturally focused on its preservation; the latter tended towards globalism and were more open to new ideas and risks. But in the 19th century, as democracy began to spread along with industrialisation and urbanisation, the equilibrium was unsettled. More and more often, conservatives found themselves outnumbered; the sweet promises of progress suited the masses much better than the wisdom of their forefathers. The forward movement accelerated, bringing with it the benefits of technology and science but also the rupture of the social fabric.

The sad fate of so-called ‘rotten boroughs’ illustrates this process well. These were small constituencies, entitled by ancient custom to send their representatives to Parliament and controlled by the landowners, which is why they were also known as ‘pocket boroughs.’ One of the most commonly mentioned, Old Sarum, used to be a site of a cathedral frequented by kings, but which had been abandoned during the 13th century and had no residents and fewer than a dozen voters as of 1831. To a modern reader, it may sound preposterous that less than fifty voters—or, as a matter of fact, one family—could have had more representation than the entire rapidly growing city of Manchester. Yet there were good reasons for this: it contributed significantly to the society’s stability, made sure that the groups that lacked direct representation could still make their opinions heard through lobbying, and provided a starting point for many talented young statesmen, especially those whose understanding of politics was greater than their ability to present their views in a populist manner. However, by 1832, the liberal sentiment grew strong enough to back reform, ending the pocket boroughs’ existence and increasing the number of voters.

The reform–the Representation of the People Act 1832, more widely referred to as the Great Reform Act–was introduced by the Whig government of Lord Grey soon after the former prime minister, Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, was forced to resign over his vehement criticism of its very idea. The Tories continued to put up a fight for as long as they could, undaunted by press and riots, but finally had to choose between desisting or losing their position in the House of Lords—in other words, between defeat and disastrous defeat. Still, they had seen revolutions and knew where this path was likely to lead; their words, spoken during the parliamentary debates, have aged well. One of the speakers, Charles Stewart, painted a picture of the future that seemed too grim at the time but turned out to be an understatement. Hansard recorded that he said that:

“[T]his Bill, instead of strengthening the Government, already too weak, added power to a party in the State opposed to all property. There was a current under the surface of society setting in strongly against the old institutions of Europe—against its monarchies, its privileges, its religion; and the Legislature ought indeed to beware of adding to its force, lest it should accelerate the ruin of those institutions under which this country had so long flourished. … The great object of the Bill was, to give Representatives to the large commercial and manufacturing interests which had grown up of late years in this country; but even this object, he feared, would not be accomplished, in consequence of the low rate of franchise fixed upon by the framers of the Bill. He believed that in Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, and the other great towns, Representatives would be chosen totally unconnected with the trade in those places. He believed that the master manufacturers would have little or no control over their workmen, and that Members would be returned to this House of the most dangerous and revolutionary principles. … Our descendants would point to this Parliament as having been the first to shake the foundations of property—as having been the first to violate, in later and more civilized times, the rights of the Church, and the sanctity of charters, and of having thus opened an inroad to those revolutionary tenets which would, sooner or later, lay all our ancient institutions in ruins.”

Should he have lived to see our days, Mr. Stewart would be horrified; so would be most of his opponents, except, perhaps, the most radical ones. And we can only wonder how much ground would be ceded by the future conservatives if society’s transformation continues at its current rate.

The urge for democratisation was indeed present among the commoners—what crowd would refuse an offer of power, however illusory?—but it was never about liberty. The Habeas Corpus Act 1679 and the Bill of Rights 1689 covered that long before the rioters took it upon themselves to ruin Nottingham Castle and storm a jail in Derby. Moreover, one could note that both Catholic Emancipation and the banning of the slave trade were not just supported by but in fact proposed and architected by the Tories of the same generation that opposed the 1832 voting reform. In fact, as one pocket borough representative argued:

I can safely aver that mine is such as would not in the least impede me in agreeing to any suitable measures, proposed for correcting abuses in borough transactions, such as I have always disapproved. … My main objection to the Bill is the violence and extent of its action: such a breach is made in the bulwarks of the Constitution as will let in, not the gradually rising and fertilizing stream—the Nile of the last speaker—but a torrent which will carry away whatever is held sacred, into ruin in its waves. I care little, therefore, about the provisions of this Bill; if it does not destroy enough, another within the year will do what is left undone; for this beginning is such a one as can never be stopped.

This prophecy also came true. The change did not occur overnight, nor, strictly speaking, was it a result of the Representation of the People Act 1832 alone. One by one, in 1867, 1884, 1918, 1928, and 1969, more reforms broke into the Parliament, altering it beyond recognition—and with it, the entire country. In their desperate search for an electorate, the Whigs had dug their own grave, ending up obliterated by the Labour Party. The range of acceptable policies gradually moved to the left, modern Conservatives being arguably much more liberal than Liberals of the past. Moreover, in the last few decades, people themselves have changed.

“As of the year ending June 2021, people born outside the UK made up an estimated 14.5% of the UK’s population, or 9.6 million people,” reported the Migration Observatory, further noting that “about half of the UK’s foreign-born population (48% in total) were either in London (35%— 3,346,000) or the South East (13%—1,286,000).” In fact, according to the 2021 census data, only 36.8% of the London population were classified as “White British”; at the same, it is worth remembering that the capital alone has 73 MPs out of 650. This does not mean, of course, that immigrants without citizenship can vote, but many qualify and the ever-present background influence of multiculturalism guides the city-dwellers’ opinions. An inquisitive observer might compare the map of the 2019 general election with that of ethnicity in boroughs and find many interesting correlations. There is also a matter of leftist ideas becoming increasingly widespread among the urban middle class—unlike mass immigration, this is not a new phenomenon, but more obvious due to its active online presence.

Would the situation be any different if rotten boroughs were still in place? There is no way to know for sure, but they might have served as a conservative bulwark against both Marxism and international corporatism. There is nothing wrong with having a globalist elite: it builds up alliances and trade, often contributes to innovation, and is concerned with economic growth, all of which are necessary for a strong competitive state. Yet it must be balanced by a nationalist elite, preferably with deep and meaningful ties to the land, history, and local culture—the hereditary keepers of pride and tradition.

Centuries pass, and the remains of the medieval walls that were once Old Sarum still look down from the majestic hill upon the growing city of Salisbury. However, it is not all that is left of the borough. Old Sarum is alive again, revived by hundreds of newly built homes. It no longer has a voice of its own, but it is a part of the ancient and very opinionated English countryside that is already pushing back against the seemingly unstoppable march of progressivism.