Oh wonder!

How many goodly creatures are there here!

How beauteous mankind is! Oh brave new world,

That has such people in’t.’

So speaks Miranda, a character in Shakespeare’s The Tempest (Act 5, Scene 1). In the course of this play, she and her father, the magician Prospero—in truth, the banished Duke of Milan—will host a group of shipwrecked nobles, delivered unto their island by magical means, before all eventually return to Italy.

The goodly creatures she is referring to are human beings, the sort of ordinary beings who populate the world she will now rejoin, along with her father. However, we may also interpret them to be us—the audience—for we are the real world to which Prospero’s magic and isolation must now give way, and he will speak directly to us at the play’s resolution, bidding we set him free. Miranda utters the words above after acquiring knowledge of young men worth loving—falling for Ferdinand, the Prince of Naples—having recently come of age after spending her life on that secluded island to which her father was banished when she was a young child.

Of course, the world is not new (it is only “new to thee,” retorts Prospero), but in a sense it is. In terms of living memory, the world is never any older than the hundred-odd years of its oldest living denizens. It starts over every generation. The less we pass on of ourselves to our children, the less supplement to living memory we carry with us, the more fully it may start over.

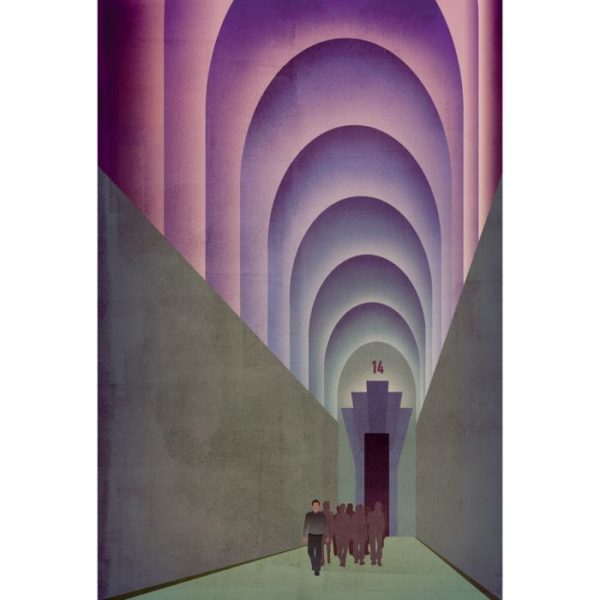

This goes a way to explaining why Aldous Huxley chose a phrase from Miranda’s epiphany for the title of his sci-fi dystopia. In “Brave New World,” a World State manages human affairs through chemical contentment and technologically enabled artificial reproduction. Members of this society sometimes holiday in parts of the world where humans still live the old fashioned way, and during one such escapade, a woman by the name of Linda, who happens to be pregnant, is left behind, forced to raise her child, John, in the wild, as it were. She and her now grown son are retrieved and brought back to the World State by Bernard, the maladaptive first protagonist of the novel (John being the second). John’s savage verve will make him the subject of general fascination, and he, for his part, will fall in love with a woman called Lenina, in whom Bernard is also interested. Alas, the rules of this society are such as to preclude long-term pair bonding, at least for Lenina, who belongs to a caste whose purpose is to provide pleasure. Eventually John will opt for seclusion and asceticism, but even this attracts the interest of the inhabitants of the World State, who flock to him. The savage eventually hangs himself, unable to cope with the impossibility of living as he would.

The newness of Huxley’s world consists of abolishing Miranda’s discovery of Ferdinand, and a rejection of matrimony and family. On the one hand, this inverts Miranda’s arch and, on the other, it turns her happy discovery of the audience (if we indulge in this reading), and Prospero’s final speech to that audience at the end of Act V, into an impermeable horizon: if in Shakespeare, Miranda passes from knowing only her island to knowing the world beyond the sea that surrounds her, Huxley presents a world that’s as closed off as an island, and precisely because all are audience, all is performance, all is scripted, regulated, controlled. In Shakespeare, the audience ultimately abolishes itself by giving Prospero leave to live rather than continuing to act on stage, just as the sea gives way to the world. Contrastingly, in Huxley, the audience never gives the novel’s hero his freedom.

“World” and “sea” are traditionally, symbolically feminine. Miranda’s return to the world, her discovery that the chaos of the sea is not all there is, that an ordered world exists beyond it, corresponds, then, to the redemption of femininity. Likewise, exile on the sea-besieged isle corresponded to Prospero’s denial of motherhood. During his exile, he speaks of Miranda’s mother only rarely and to cast aspersions on her (implying his daughter’s illegitimacy), so that she has no memory or knowledge of her mother. He also insults his own mother, who he blames for his brother’s misbehavior. The rejection of mothers, then, seems to accompany that chapter of Prospero’s life marked by isolation and dabbling in the magical arts which he is now choosing to leave behind.

Importantly, Prospero’s power over the island replaces a previous, perverse feminine order, that of the witch Sycorax. As an aside, the idea that matriarchal witchcraft and nature worship may lead, by way of reaction, to a masculine legalism that disenchants the world, occurs across the work of various artists, including, possibly, that of Blake. In this sense, Prospero’s magic would be the male counter to that of Sycorax, a perspective Huxley brings to the fore by making his equivalent to Prospero a technological superstate obsessed with taming nature.

If Prospero banishes the role of mother from his rearing of Miranda, he nonetheless must be polarized by something that fills that vacuum. Instead of spousal relationship, this takes the form of antagonism towards the outer world. Prospero has fathered her in opposition to the dark femininity of the sea, and so, we might suggest, the sea-like audience is the dark womb that births the performance, for nothing would occur on stage were it not that an audience receives it and gives it life in the perceiving of it. The audience was the unfortunate replacement for the genuine motherhood that Prospero suppressed,

Yet, he ultimately overcomes this by arranging his daughter’s marriage and returning to that world. His parting words to the audience, “let your indulgence set me free,” would be analogous to the recovery of society from the wind-swept sea and renunciation of magic: it is an end to the tyrannous authority (magic) that serves as dialectical compliment to chaotic world (the sea, the audience in its negative sense). The Tempest is every bit the comedy, where Huxley’s take is a tragedy—one in which John dies and the species languishes.

In Huxley’s dystopia, the abolition of motherhood also leads to alienation. The breeding of humans is taken up by the state, and occurs according to the dictates of efficiency-maximization (96 people can be produced from a single sperm and egg-cell). The collective, the audience, is now the mother. Here again the relationship is one of antagonism between science and modern prosperity (Huxley’s version of Prospero) and nature—nature being repeatedly disapproved of by the technocratic elites (“a prodigious improvement, you will agree, on nature;” “out of the realm of mere slavish imitation of nature into the much more interesting world of human invention;” “What man has joined, nature is powerless to put asunder;” “A love of nature keeps no factories busy. It was decided to abolish the love of nature, at any rate among the lower classes,” and so on).

We are likening Prospero’s control over spirits (prominently Ariel, to whom he will finally grant freedom) as well as people (namely Caliban, who may be an island native) to the technological harnessing of natural forces and human instinct in Huxley. Again, Prospero’s arch is redemptive: he frees Ariel, forgives those who had plotted to kill him, recovers his position as Duke of Milan, and turns away from magic. By the end of The Tempest, he no longer wishes to be the authority that has recourse to dark arts (magical or technological) in order to keep the amoral flux of audience opinion at bay.

Today, the degradation of sexual and familial norms does indeed operate as a system of control, and one way in which this degradation occurs is by treating gender as pure performance—either because it is conceived as a secret psychic recess entirely un-manifested in the givenness of bodies, or because it is a purely cultural, and therefore individually redefinable, category. The literary works I explore here, as suggestive of the consequences of laying gender difference aside, are briefly touched on by John Milbank in the context of transgenderism.

Both the essentialist notion of, for example, a set gender identity that is entirely decoupled from biology, and the more subjectivist (Judith Butler) conception of gender as pure cultural artifact that can be constantly altered, are conducive to performance. In both cases, whether one chooses or discovers one’s role, it is only discernible to others through performance, which must become progressively codified.

The idea that the world is a vast audience crystalizes in the prevalence of social media, and has as its natural correlate a certain weakening of the subject, who paradoxically becomes a function of performance the more the culture around him emphasizes monologuing, personal trials, “authenticity” and “being oneself.” These are all intended as superficial stage props. They are the rhetorical version of costume and set pieces meant for verisimilitude.

To speak of reducing one’s being, or at least one’s social being, to performance is actually just a way of describing absolute liberal individual autonomy and the making of social categories into consumable, market options. We can access any category, including gender, and are in this way, theoretically, entirely exchangeable with any other autonomous individual consumer. We are, together, a mass of anonymous audience members who occasionally act out some arbitrary role for our miasmic collective.

There being no prior essence on whose basis such individuals act (outside of a baseline utilitarianism)—or at least no prior essence discernible through traditional categories and derived from something other than psychological impressions—these individuals become mere reception and reaction. This defines the audience member. He is receiving images and reacting, or judging. The only real agents are the seated audience and the hidden director who engineered the performance: Miranda’s father, the magician, and the anonymous audience, like the sea surrounding her, before it is revealed to be an ordered world at the end. Actors are co-determined by the audience and the director (society becomes a function of state policy and market force). The magician and the sea are analogous to today’s political idolatries, the Left’s state and the Right’s market: the director of the show, the arranger of happenstance, the dark-magician Prospero, is the state, and we, the audience, are the market.

Yet there can hardly be a greater obstacle to the designs of a production’s director (the state), on the one hand, and an audience’s prerogative on approving or disapproving of the performance (the market), on the other, than the fact that the creation of new persons falls to the choices made by individual men and women. Correspondingly, few things can limit a person’s autonomy more than the responsibility to rear a new life. Collectivism and individualism, then, must be allies in abolishing ordinary family formation, just as they are secret allies in everything else.

The most obvious obstacle to pure performativity is the brute fact of biological difference and parenthood. Family constitutes a differentiated, intimate stage in which our audience is the parent whose reactions to our behavior mold the persona we take out into the world. Insofar as family, and other traditional, organically occurring institutions are endowed with their own standards and perpetuate cultural forms, the state or the market cannot monopolize culture. But such a monopoly is precisely what the “brave new world” which is all a stage, or rather, which is all audience, is meant to accomplish: A single audience, a fractal panopticon, which mobilizes society itself by instilling its standard of political and social correctness, and whose excesses periodically justify the enforcement of the performance’s script. Human community is parodied by collectivism, just as human action is parodied by mere acting. For this reason, to break the dialectic, The Tempest’s happy ending could not have been other than a marriage.

Things work out for Miranda. Just as the sea is abolished in John’s Apocalypse, the stormy tides that once surrounded Miranda on her island are revealed to give way to a whole wide world full of self-existing persons just like her. And following Prospero’s addressing of the audience, we may say that we who watch the performers are that brave new world she previously hailed, one willing to let Prospero and his family abandon their roles, their performances, and live freely, as he asks us to do. In responding positively to Prospero’s bid for freedom, we are not only a benevolent audience, but no audience at all—by giving him leave of his role as actor to live life, we also take our leave and become, not an audience, but again differentiated persons who participate in our own stages as actors and directors.

Huxley simply denies this final, liberational gambit. Appropriately, his opposite use of Shakespearean symbols leads to an opposite end. The same symbolism in The Tempest is twisted in a sinister direction, in line with Huxley’s ironic use of the young woman’s phrase “brave new world.” John, like Miranda, is an exile, in that his parents do not come from the world he is raised in. But unlike Miranda, he is not brought up by a father, but by his mother. This indicates that the region outside the World State is not analogous to Prospero’s island—rather, the World State is that island. And whereas Miranda will leave the island presided over by dark magic, John will enter such a world, and never again be allowed to leave. Prospero might reject his occult knowledge, but Huxley’s Mustafa Mond, the Resident World Controller for Western Europe, never does, denying John’s request for freedom. It is significant, then, that John should try to retire to a lighthouse, a place of vigilance, a sign of his wanting to stand above the proverbial waters, to keep from being engulfed, and perhaps, somehow, to guide others.

Here, the audience remains the sea; remains that chaotic instability represented by the waters. And this sea, this collective, drowns John by forcing him to be a spectacle for them, to play the actor to their audience, even in his self-imposed isolation and attempted rediscovery of the religious dimension of life, of solitude, and intimacy. At the novel’s close, masses and media gather and voyeuristically implore John to engage in his strange ascetic disciplines for them to gawk at.

John’s love of Lenina, which could have been redemptive, like Miranda’s love of prince Ferdinand, is thwarted by the World State’s hostility to family—the sea comes to claim the land, even unto the solitary lighthouse. The crowd that gathers about John finally descends into an orgy which, despite himself, he joins. The promiscuity of the woman he loves, and his regret at his own participation in it, ultimately leads him to commit suicide.

The abolition of wives and mothers in The Tempest and Brave New World may help us understand our own age and what’s in store for it: techno-dystopia as primarily the end of marriage and motherhood. Our behavior as each others’ audience, whether in granting Prospero his freedom or in hounding John outside his lighthouse—the degree to which we are willing, or able, to grant human dignity—will reveal whether we are ready to be loyal enforces of tyranny, or else might yet resist its coming.