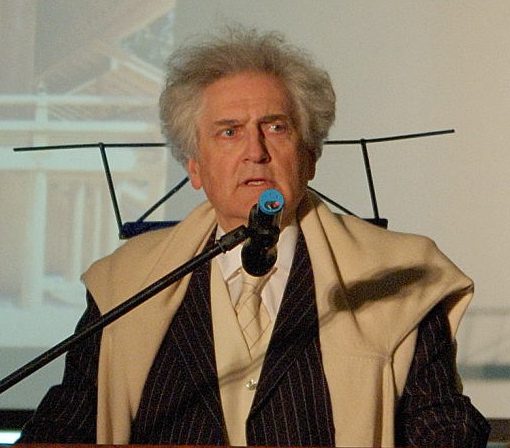

Following up on a previous essay on the success of Guatemala’s new Cayalá township as a springboard for discussing traditional urban planning and architectural principles, we will explore some of the ideas of Cayalá’s designer, the Luxembourgish architect and theorist Léon Krier, as laid out in some of his works, like Drawing for Architecture (also see here).

Cayalá does not present us with sprawling structures that outstrip the landscape, but with mainly Spanish colonial buildings, classical monuments, and deliberately, organically irregular walkways that force cars to slow down and prioritise pedestrian traffic.

For Krier, apart from utilising time-tested, geographically and climatically appropriate materials and techniques, traditional architecture is generally adapted to the “human scale,” in contrast to the large, corporate office space (a kind of white-collar correlate of the industrial factory), which is the paradigmatic exemplar of modernism and the modern city.

According to Krier, in order to retain this human scale, when a city needs to expand, it should duplicate its centre and so retain proximity between residents and services, rather than sprawling and centralising.

Krier describes the overdevelopment of city centres in which large company buildings reign supreme as reflecting an illegitimate pursuit of wealth that trespasses on the public sphere, contrasting this with the legitimate economic activity that comes from opening businesses in and among residential areas, which also avoids the isolation of U.S.-style suburbs in which one has to drive one’s car just to get a coffee or a haircut.

Traditional architecture will further tend to invite interaction by revealing more of its details (filigree, finish, etc.) than the minimalism of modern steel and glass constructions, which do not tell you much more about themselves from up-close than they do from a block away.

Krier thinks in terms of what I would describe as the “Yin-Yang” dyad of architectural and urban planning theory: the two complementary poles of “vernacular,” or domestic, on the one hand, and “classical,” or monumental, on the other.

The “vernacular” manifests as buildings and private spaces, or Res Privata (also Res Economica, “economy,” deriving from oikos, “household”), and belongs to the artisan. The “classical” manifests as architecture in a grander sense and public spaces, the Res Publica, and belongs to the artist.

These two are also clearly expressions of femininity and masculinity. But even if the Res Privata is feminine, it will include masculine elements analogous to those of public institutions (“paternal” authority), and likewise, even though the Res Publica is masculine, it will include feminine elements. We may think of how the Roman father of architectural theory, Vitruvius, distinguished between Doric masculinity and Ionic femininity. The Ionic column in a public building “gestures” towards the private; its delicate flutes and curved design relax the mind into the nurturing frame of domesticity. It is the necessary presence of the maternal in an otherwise patriarchal space, so to speak (the white dot in the black “Yin” of the Yin-Yang circle).

In this context, we may also suggest that each sphere contains two kinds of spaces, one more extroverted and one more introverted: The private sphere includes economically active assets like shops and storehouses as well as private homes, and the public sphere is composed of government houses, like the town hall, but also walkways, parks, and so on.

As I understand Krier, his two poles can manifest as the extremes of different axes, such as “size,” “type,” and “style.”

In terms of “size,” vernacular and classical simply refer to small and large, respectively. A vernacular “type” would be something like a cottage, compared to a monumental palace. In contrast, a palace-sized cottage and a cottage-sized palace would be somehow awkward. Krier refers to the example of a “midget” monument, which would come across as effete and pretentious, and of the opposite “monster” shed, which would seem gross and pompous.

The point of the monument is to be seen from a distance, and the point of the shed is to store an appropriate amount of hay or house an appropriate number of animals, for example. Scale matters to their overall character. We grasp this intuitively when we feel unsettled by vast industrial holding pens in mass farms where animals have little mobility.

Finally, “style” seems to refer to the actual aesthetic facade of a construction. A Greco-Roman tympanum (the triangle on top of a temple) and rows of large Doric columns are meant for the Res Publica, as in a congressional building or semi-public palatial estate, not the Res Privata, a permanent domicile. The latter would not be “homely.”

The following illustrations show us how Krier conceives of a proper complementarity between the vernacular and the classical. He calls this complementarity the cultural “apogee,” as distinct from both an unbalanced vernacular/private “austerity” and a monumental/public “imperial carnival.” Politically, we might liken this apogee to the balance between anarchic and authoritarian extremes or isolationist and imperialist deviations.

Krier’s observations highlight that, as with much of the modern or postmodern cultural moment (modern art, contemporary “woke” politics, etc.), architectural modernism and postmodernism are fuelled by a kind of perverse adolescent naïveté that twists into excitement at mere transgression.

It is a rush of energy to break bounds and combine things that don’t really fit. But wallowing in contradiction, by its nature, is a banal, ultimately perverse, and dysfunctional experiment—one that will grow more rotten the longer it is held to by ageing intellectuals and jaded cultural elites.

The opposite instinct is to match and complement (for example, vernacular with a small cottage in a mountain alpine style or classical with a big palace in a Doric temple style).

The love for things that fit and make sense together delivers long-term functionality while also finally satisfying our aesthetic and intellectual faculties.