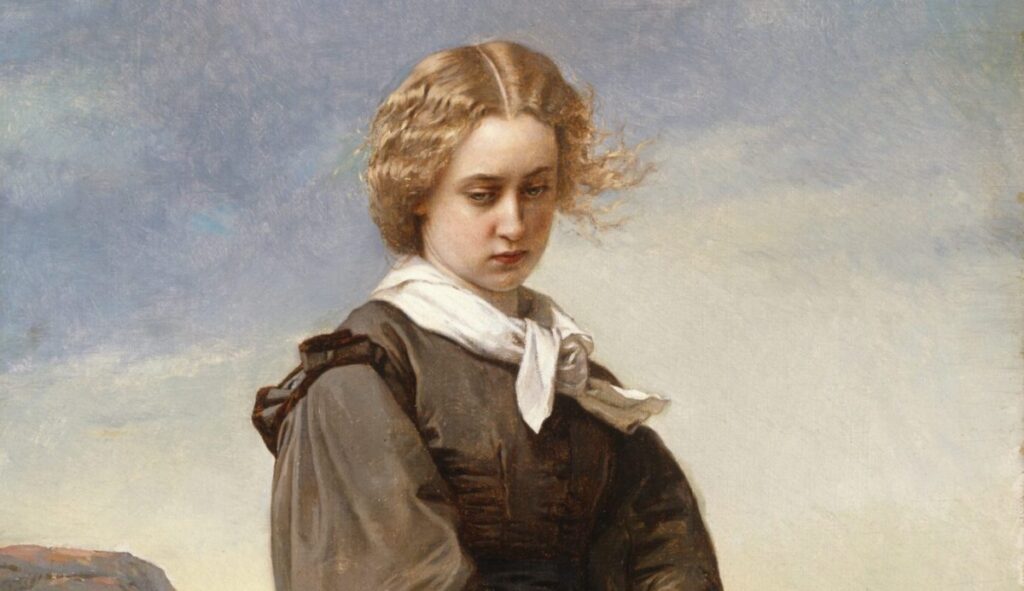

“Love’s Melancholy” (1866), a 51.4 × 35.6 cm oil on canvas by Constant Mayer (1832-1911), located in the Art Institute of Chicago.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Uncertainty: eleven letters on a page; four syllables on the mouth; untold hours of darkness in the mind; perhaps days, months, or years of anguish in the heart. The word comes from the Latin incerta—those things that are not clear, reliable, or fixed. The psalmist speaks of how the Lord revealed to him hidden and secret wisdom: incerta et occulta sapientiæ tuæ manifestasti mihi (Ps. 50:8). But this experience appears to be the exception; the illumination of the dark, the stabilization of the wavering, or the solidifying of the unreliable seems a rare experience. Uncertainty faces us more regularly than certainty. What are we to make of this?

First, we need to determine—or remember—what is in fact certain. We often forget how much is certain. In Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Eomer, the Marshal of the Mark of Rohan, considers the protocol to follow in dealing with the mysterious members of the Fellowship. “How shall a man judge what to do in such times?” he asks, and Aragorn replies: “As he ever has judged. Good and ill have not changed since yesteryear; nor are they one thing among Elves and Dwarves and another among Men. It is a man’s part to discern them, as much in the Golden Wood as in his own house.” Simple to say, but a truth that’s hard to grasp in the darkness of present uncertainties.

Yet the truth that “good and ill have not changed since yesteryear” can do much to dispel our uncertainties. The binding, choking, paralyzing effects that uncertainty often creates in our hearts are generally loosed by truth. Though the truth does free, it often frees through, in spite of, or in company with suffering. In the midst of the battle of the Pelennor fields, Eomer sees what he thinks are enemy reinforcements approaching. Rallying his men, he sings:

“Out of doubt, out of dark to the day’s rising

I came singing in the sun, sword unsheathing.

To hope’s end I rode and to heart’s breaking:

Now for wrath, now for ruin and a red nightfall!”

In the face of evil, Eomer summons his courage, and realizes that defense of the good is capable of banishing despair:

These staves he spoke, yet he laughed as he said them. For once more lust of battle was on him; and he was still unscathed, and he was young, and he was king: the lord of a fell people. And lo! even as he laughed at despair he looked out again on the black ships, and he lifted up his sword to defy them.

Eomer’s love of his land and people is a love unto death. This love has the power to overcome uncertainty, or perhaps to operate in spite of it. Whatever may be uncertain, it is certain—certus, trustworthy, fixed, believable—that dying for the beloved, for the good, is a worthy use of life. Thus, it is that Eomer emerges “out of doubt,” “singing in the sun” and finds that riding to the end of hope must lead to “heart’s breaking.” At this moment of lightsome darkness, however, the ships’ flag is unfurled and reveals them to be not enemies but reinforcements led by Aragorn who has just passed through the “paths of the dead.”

But what can a fictional account teach us, concretely, about the uncertainties of prayer, family, work, and all the rest? We learn, first, to recognize the place that self-sacrifice—bloody love—has in all these areas. Second, it urges us to remember how “heart’s breaking” is a possibility that must be embraced in any endeavor of greatness. And finally, we see that often we fool ourselves into thinking we have “ridden to hope’s end” when we have barely begun, and when help is around the corner—that help which has passed through the “paths of the dead” and still bears the marks of Bloody Love in His glorious Body.

In prayer, often the temptation is to overcomplicate rather than simply to express what is in your heart. The Benedictine monk, Dom Hubert van Zeller writes:

We may use many forms and formulae when we start off upon our course of prayer, but if we persevere and make of it a life, and not merely a series of exercises, we shall find that in the end our activity reduces itself to something very simple. Love has little use for multiplicity; love is direct and obvious and is not bothered about originality.

When it comes to relationships, the demand for certitude of the other’s devotion is often what sours an otherwise perfectly good friendship. With those friendships that develop into romances, which in turn lead to family life, the principle of “bloody love” finds one of its highest expressions. “Bring God to love? But He is already there,” writes van Zeller. “God is love; human love is simply one side of it stretching out to the other. Human love is meant to tell us something of Divine love. This is primarily what it is for.” He continues, now speaking specifically of spouses:

Two, then, in one flesh; two also in one spirit. The bond of self-giving sanctified by the sacrament. Generosity the beginning, the end, the condition. Sacrifice. Go to marriage for what you can get, and you are disillusioned; go for what you can give, and you find yourself immeasurably the richer for your gift.

Van Zeller goes on to say: “Go with your eyes open, looking for the beauty which is in marriage and prepared to pay the price. Looking for what love has yet to offer when the early blossom has blown away, and still prepared to pay the price.” This is a place of certainty all would-be lovers must return to. Like the approach of the supposed enemy, the approach of possible suffering must inspire us to go “singing in the sun,” ready to ride to hope’s end and heart’s breaking. “Costly must be love, else is it luxury. Hopeful, grateful, humble … ready always to acknowledge unworthiness in the face of a gift so excellent that none but God Himself could have devised its possibility.”

The relation between leisure and work falls into place when we come to acknowledge the primary truths upon which we are building our life: we work to provide for those we love and relax to rejuvenate ourselves and delight in the presence of those for whom we provide. If work and relaxation are somehow defeating these ends, something is out of balance in us or in the activities and work, and consequently needs to be adjusted.

While the experience of uncertainty and darkness is an invitation to find our certainties, this itself may not present an opportunity to avoid or escape suffering. In C.S. Lewis’s dystopian novel That Hideous Strength, spouses Mark and Jane become uncertain of everything that has shaped their worlds. In this uncertainty they discover new, less empirical certainties. The approach of evil, and even its touch, does more to convince them viscerally of true certitudes than any discursive reasoning could have achieved. Suffering is not inimical to certitude. The suffering that often accompanies uncertainty may be transformed from pathological to functional pain if we can find its source and let it be healed.

Perhaps our conceptions of “happiness” and “suffering” need to be reformed:

Happiness is not something which we feel we have a right to in our free time; it emerges from the set-up of our lives; it is the colour of our work; it has nothing to do with being in or out of office hours; it must not be confused with recreation … Happiness comes naturally if you let it. Look for it you must, but don’t look for it anxiously or with one eye upon the happiness of others. Take it, together with unhappiness, in your stride.

Thus, according to Dom Hubert, happiness and suffering are intrinsic to life, not add-ons. They both come if we unsheathe our swords in the pursuit of arduous goods, committed to riding “to hope’s end and to heart’s breaking.” Where will this lead us? Ultimately it cannot but lead us to resurrection, as Eomer’s verse, re-written for the burial of King Théoden, so poignantly reminds us:

“Out of doubt, out of dark, to the day’s rising

he rode singing in the sun, sword unsheathing.

Hope he rekindled, and in hope ended;

over death, over dread, over doom lifted

out of loss, out of life, unto long glory.