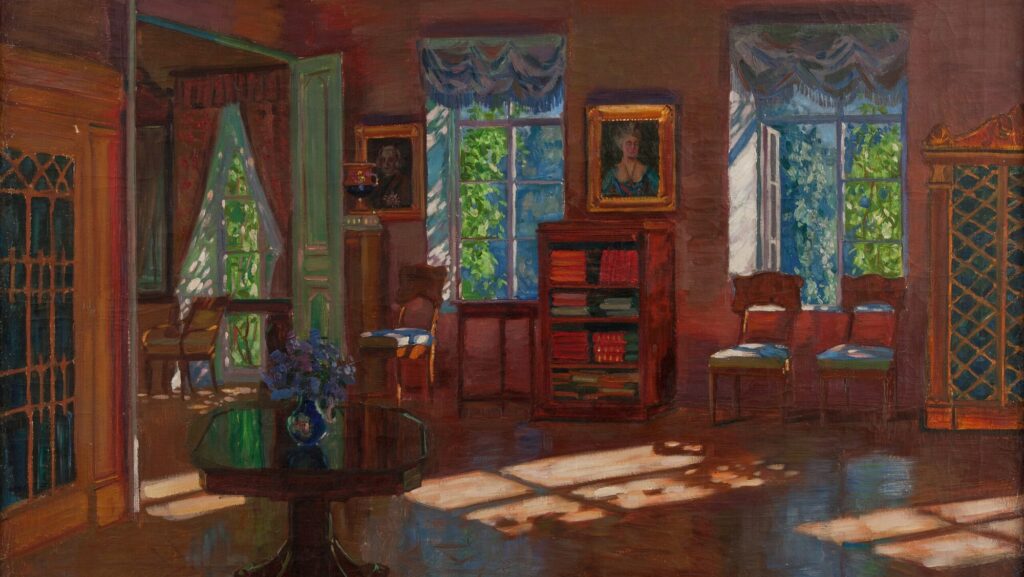

“Old Library” (1916), a 76 cm by 105 cm oil on canvas by Stanislav Zhukovsky (1873-1944), located in the National Museum in Kraków, Poland.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

In an earlier article for this publication, I noted that “The aesthetic aspect of culture is nothing more or less than works that build upon and respond to one another in the form of an historical conversation with many voices directed to similar ends.” More recently, in an article that considered the influences, Romantic and otherwise, upon Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, I wrote of that author’s “supreme gift of identifying the common thread of humanity that runs through the great texts” and “his ability to pick it up to weave it into a new narrative tapestry—one which reflects the many colours and attitudes of the works that he has read, but also one which is of a shape and mien utterly his own.” Both of these observations stem from something fundamental to artistic culture: its essential self-reference and encoding of influence as a creative conversation that echoes down the ages.

In The Aesthetics of Music, Roger Scruton makes a similar argument for music as a cultural creation, but he uses a literary analogy to do so (as he does throughout the book), beginning with an example by the Japanese poet Matsue Shigeyori (ca. 1602-1670), also known as Ishu:

Hey there, wait a moment

before you strike the temple bell

at the cherry blossoms.

To understand this poem you must capture the allusion to the Noh play Miidera, and also to a certain poem in the classical anthology entitled Shin Kokinshu. In the first of these a madwoman, about to strike the temple bell, is stopped by a priest with the words ‘Hey there, wait a minute! What you are, a mad woman, doing striking that bell?’ (a speech which, in the original, contains all the words of the first line and the third). The poem from the Shin Kokinshu supplies the remaining words: it describes the fall of cherry blossoms at evening while the temple bell is struck. The reader must experience the fusion of these two allusions in a single revelation: the striking of the temple bell, which is the symbol of eternal things, becomes the very act of madness that precipitates the fall of mortal beauty. Without the allusions, it is impossible for these words to convey such a meaning: with them, they suggest not only a poignant thought about the human condition, but also a community of people who share this thought, and who are comforted by sharing it.

Scruton uses this example from outside of English-speaking (and even Western) culture in order to make a point that would otherwise be more difficult to grasp. Reading it without an understanding of its literary allusions, the poem nevertheless has a certain evocative beauty and a simplicity of expression that combine to create an agreeable impression upon the reader. But it absolutely lacks the depth and emotional resonance that are present when the allusions are recognised. When that is so, reading the poem adds the emotional registers of those other works to its own and then synthesises them into a whole that expresses, as Scruton succinctly observes, a mad stroke against the eternal things that brings about the fall of mortal beauty. Such a meaning is indeed a “poignant thought about the mortal condition”—that is, a timeless truth paralleling not only the remotest past of the Fall but also the immediate present of our own addled age, characterised by its resentful assaults on the eternal things and its concomitant ugliness.

The connexion between a given work and the other works which have preceded it might be imagined—like Bloom expressed it—as a web of influence. However, the term “influence” seems loaded with negative connotations, as if the author is rendered helplessly suggestible through contact with the past, any novel genius being overwritten by the collective force of generations of past authors. Certainly, this view seems to have taken hold amongst some sections of the reading (and viewing, and listening) audience, sometimes influentially. For those labouring under such a misapprehension, their desire to cut all ties with the past is not an act of vandalism but one of creative preservation, as Scruton notes in The Aesthetics of Music during his discussion of Schoenberg:

Here, briefly, is Schoenberg’s argument: tonality is not the ‘natural’ and inescapable thing which its defenders suppose. It is part of a particular tradition, which was not initially tonal, and which became so only through historical development. In time tonality became a unifying force in music, the principle which enables us to hold a piece of music together as we listen: that is why tonal music is so readily comprehensible. But tonality has now exhausted its potential, and must be replaced if new artistic gestures are to be possible.

Scruton takes considerable time and care to refute Schoenberg’s argument because the people who have adopted Schoenberg’s view are not motivated by malice but by a misguided conception of the nature of creativity, art, tradition, and the role of the individual author of artistic works. It is this misguided conception that motivates some—but not all—of the antipathy directed against established figures in the various canons of music, literature, and other forms of art. Such an antipathy stems from the sense that no truly new art can be created because of the continuing influence of the canonical works, which continue to shape audience tastes such that anything that deviates too far from those works is doomed to the margins. Therefore, they take Schoenberg one step further, not merely repudiating the past forms and modes as exhausted but also attempting to purge the canon of works that they perceive as taking attention away from their own efforts. For this reason, one can readily find arguments that classics by authors such as Shakespeare, Dickens, Jane Austen, and J.R.R. Tolkien should not be stocked on bookstore shelves because they take up space that could be afforded to new (and supposedly more relevant) authors.

Such a view misunderstands the role of art, which, as Ishu’s poem shows, is at the height of its meaningful valences when it is in conversation with its own tradition. It is far better, then, to imagine the vast history of artistic creation not as an occasion of anxiety in the form of a web of irresistible and inescapable ‘influences,’ but rather as a conversation between artists who respond to and echo one another in ways that generate meaning.

The interconnected nature of the great works of art means that one must learn the tradition in order fully to appreciate the individual works that exist within it. Of course, as is the case with Ishu’s poem, even without such broad knowledge, it may still be possible to appreciate certain aspects of individual works. But even these appreciations must be, at some level, dependent upon tradition, as reading Richard Wilbur’s “Having Misidentified a Wildflower” may show:

A thrush, because I’d been wrong,

Burst rightly into song

In a world not vague, not lonely,

Not governed by me only.

Here, identifying the pleasing, formal aspects of the poem (its iambic trimeter and rhyming couplets) is no more or less than to judge how it conforms or differs from those definitions, which identify and express as a principle what is in fact the history of the development of poetic conventions. Hence, it is possible to identify anapestic substitutions, the gentle enjambment of the second line, and so on.

For these reasons, familiarity with the artistic canon is essential for those who would appreciate art as much as for those who would create it—such creation being an act of participation in an historical conversation, which necessarily requires understanding the nature of that conversation. Western liberal education has, until quite recently, recognised this reality and so served as the schoolroom for the preservation of its culture and the means by which seriously to engage with it—but no longer. Today, many Western educational institutions are staffed by faculty who express indifference or outright antipathy towards their own cultural heritage. Their students, in turn, are not given the exposure and instruction needed to make and appreciate the traditional cultural intersections, or they are taught that those connexions are merely a by-product of historical coincidences and that they have led to an exhausted and socially irrelevant end, wanting replacement with novel forms better suited to an age of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

The recognition of these developments is part of the occasion for the contentious battles being waged over education systems in the United States. But it is also responsible for the success of the institutions that have resisted in the face of powerful and moneyed opposition. Programmes teaching the great books, or foundational texts, have little trouble finding students, and smaller colleges and universities that have foregrounded classical approaches to education have been rewarded with record enrolments. Consequently, in addition to the duty of providing students with cultural literacy, there are economically pragmatic reasons to provide students with a grounding in the artistic canons of Western culture. The work may take a generation or more, but there are positive signs that, in years to come, Western culture may endure amongst a people still able to appreciate Shakespeare, Milton, and Melville. If it is to be so, the work must be done now.