Portrait of Claudio Monteverdi (ca. 1630), a 84 x 70.5 cm oil on canvas by Bernardo Strozzi (1581–1644).

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

Besides, I have seen that [in a certain scene in the opera Le nozze di Tetide] the interlocutors are winds, young Cupids [Amoretti], breezes and mermaids, so we will need a lot of sopranos. And it should be added that those winds, i.e., the breezes and boreal winds, should sing. But how am I to imitate the speech of winds in music, if they do not speak? And how, by employing them, can I move the audience [movere li affetti, move the passions]? Arianna moved because she is a woman, Orpheus moved because he is a man, and not a wind.

Letter from Monteverdi to Alessandro Striggio, 9 December 1616.

In 1663, the Bolognese painter Giovanni Andrea Sirani painted a beautiful canvas entitled Allegory of the Three Arts, or The Three Sisters Painting, Music and Poetry. Music is depicted as a singing young woman holding a cornetto, a wind instrument, in her right hand. In her left hand, she holds a sheet of printed music, whose notes and lyrics are clearly legible. This is “Il lamento d’Arianna” (The lamentation of Arianna), taken from the opera L’Arianna by Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643), which was published together with two other pieces by the same composer in 1623 by the Venetian publisher Bartolomeo Magni. That this lament is depicted in the painting is remarkable, as Monteverdi had been dead for 20 years when the canvas was painted. Moreover, L’Arianna was first performed on 28 May 1608 in Mantua, where Monteverdi was at that time employed by Duke Vincenzo I Gonzaga as the court’s chapel master. By 1663, therefore, the music of “Arianna’s Lament” was already more than half a century old.

In Baroque Italy, successful operas were occasionally revived in adapted form after the first series of performances in subsequent years, but usually fell quickly into oblivion after the first run. “Arianna’s Lament,” on the other hand, remained unabatedly popular for decades. There really is something special about this piece, then. On 10 September 1607, Monteverdi’s wife Claudia Cattaneo had died of tuberculosis. She left behind Claudio and two young sons. No wonder the almost unbearable expressiveness of “Arianna’s Lament” has often been associated with Monteverdi’s own fate. The composer was fully aware of the extraordinary significance of his work. Otherwise, he would not have reworked the lament into a five-part madrigal, published in his Sixth Book of Madrigals (1614). And he would not also have made a sacred version of the piece, which was given a place as “Pianto della Madonna sopra il Lamento d’Arianna” (Lament of the Madonna based on the Lamentation of Arianna) in Monteverdi’s Selva morale e spirituale, a large collection of sacred music published in Venice in 1640. A year earlier, L’Arianna had been staged again at the Venetian Teatro San Moisè, albeit undoubtedly in a form adapted and updated by the composer. It is also known that Monteverdi initially did not allow copies of the “Lamento” to be made by copyists, so as to guarantee that copies of this hit could only be sold by the composer himself. A lucrative trade! Anyway, Sirani—or his patron—apparently thought immediately of the ‘old’ but deeply expressive and still widely admired lament from L’Arianna when music had to be personified in a painting.

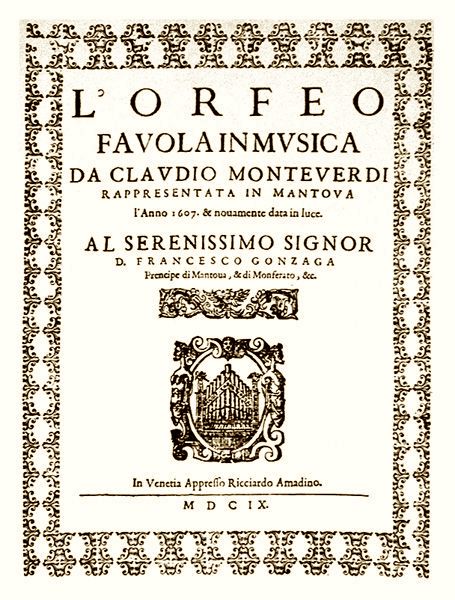

Sadly, all that remains of L’Arianna is this lament. The rest of the music has been lost. Fortunately, Monteverdi’s earlier opera L’Orfeo, first performed on 24 February 1607 in the Palazzo Ducale of Mantua, was spared this fate. This opera is generally regarded as the first perfect masterpiece in operatic history. Earlier contemporaries such as Jacopo Peri, Marco da Gagliano, and Giulio Caccini had already written fine operas, yet by no means achieved the same musical richness and eloquence as Monteverdi.

The genre of opera was still brand new when L’Orfeo and L’Arianna were composed. It had emerged a decade or so earlier in Florence within artistically orientated academic circles, that were trying to revive the ancient Greek tragedy in a contemporary form. Letters to Alessandro Striggio, the librettist of L’Orfeo and of the opera Le nozze di Tetide—the last of which was never completed by Monteverdi—reveal how consciously and critically the composer assessed and tried to increase the dramatic possibilities of the libretto. Sometimes he asks Striggio to insert some extra lines of text, sometimes to create space for a dance or a purely instrumental movement, sometimes to provide more variation and contrast. But above all, he asks Striggio for believable characters, real people of flesh and blood (as the above quoted passage from his letter of 9 December 1616 shows).

So, what makes L’Orfeo so unforgettable? First, the story itself: the subject of eternal love that (temporarily) overcomes even the limits of death is a recurring motif of all great mythologies. Second, Striggio has cast the ancient myth in a masterly libretto. The first act is all mirth and joy over the approaching marriage of Orpheus and Eurydice, expressed in lyrical arias, instrumental dances, and brilliant choral movements. In the second act, the mood suddenly darkens completely when a female messenger comes to inform Orpheus that Eurydice has died as a result of a poisonous snake bite. This is one of those moments in which Monteverdi gives the new recitar cantando (reciting in sung form) such an enormous expressive charge that you never forget this passage after listening to it. The fact that Monteverdi had access to great singers and an unusually large and colourful orchestra in Mantua must also have been a great source of inspiration for him. Remarkably, Monteverdi employed the most modern means of the recitative style developed in Florence, but also stuck to the tried-and-tested contrapuntal techniques. Tradition and innovation, Renaissance and Baroque, merge into a perfect unity in L’Orfeo.

Such was the success of L’Orfeo that the music appeared in print two years later, with a flattering dedication by Monteverdi to Francesco Gonzaga, the eldest son of his employer Duke Vincenzo I. At the time, incidentally, the severely overworked and depressed composer had already tried for some time to flee the Gonzaga’s court, where non-payment was the order of the day, and find new employment elsewhere. A clandestine trip to Rome in the autumn of 1610 had probably led to the desired audience with Pope Paul V, but had not resulted in a permanent position in the Eternal City. Monteverdi was more successful three years later in Venice, where he was appointed chapel master of the Basilica di San Marco on 19 August 1613.

The ancient Basilica di San Marco then functioned as the private chapel of the doge, the political leader of the Venetian Republic, and would not be elevated to the rank of cathedral until the 19th century. From then on, Monteverdi’s life was mainly dominated by composing church music and directing the famous music chapel, which was among the largest and most famous in Italy and consisted of more than 50 singers and instrumentalists on liturgical feast-days. On 24 June 1620, the then 23-year-old Dutch composer and poet Constantijn Huygens saw in another Venetian church “the widely acclaimed Claudio Monteverdi” conducting church music for the Feast of St. John. In his French-language travel diary, Huygens added that it was “the most accomplished music I have ever had the pleasure of hearing in my life.”

In July 1630, a terrible plague epidemic begins, wiping out a third of the Venetian population in less than a year. Partly as a result of the impression made by the epidemic, Monteverdi decides to be ordained a priest in 1632, at the age of 65. But even the ‘reverendo Signor Monteverdi’ did not deny his passion for music theatre. After the Teatro San Cassiano in Venice had been rebuilt in 1637 into the first publicly accessible opera theatre in history, in the following years the Teatro San Moisè and the Teatro Santi Giovanni e Paolo were also adapted to allow opera performances. All three of these theatres were owned by Venetian noble families, but were open to any paying visitor and thus much more accessible than the court theatres. In fact, things were often quite commercial. Not for nothing did the famous librettist Aurelio Aureli claim that he wrote more “for the one who spends money than for the one who reads.”

A direct consequence of the new opera fad was that Monteverdi, who was already very old by the standards of the time, experienced a veritable ‘Indian Summer’: the aforementioned revival of L’Arianna in the 800-seat Teatro San Moisè in 1639 was followed by three major new operas, the music for two of which (Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria and L’incoronazione di Poppea) has survived. Stylistically, the contrast with L’Orfeo is enormous: the chorus hardly matters in the late operas and the orchestra is limited to a handful of strings and basso continuo. The music consists of recitatives, punctuated by arias, duets, and trios. All emphasis is now on beautiful and passionate singing, and it is no coincidence that the aria occupies an increasingly important place. Comic scenes are also now inserted, which the old Monteverdi sets to music with unimaginable vividness and power.

Although many of Monteverdi’s dramatic compositions—such as Proserpina rapita from 1630—have been lost, the three operas by him that have survived are sufficient to count him among the greatest opera composers of all time. The fact that in the surviving versions not all the music of these operas is by him—there are strong indications, for instance, that the famous final duet ‘Pur ti miro’ from L’incoronazione di Poppea was composed either by poet-composer Benedetto Ferrari or by the composer Francesco Sacrati—does not detract in any way from this verdict.

No less important was Monteverdi as a composer of church music and madrigals. In the eight madrigal books printed in Venice during Monteverdi’s lifetime, we can closely follow his development as a composer. In the first three books (1587, 1590, 1592), the influence of older composers such as Luca Marenzio, Giaches de Wert, and Monteverdi’s teacher Marc’Antonio Ingegneri is still strongly felt. By the time the Fourth Book of Madrigals (1603) appears, Monteverdi’s own style is fully crystallised and so free in some—especially harmonic—respects, that he is vehemently attacked by the conservative music theorist Giovanni Maria Artusi. In the Fifth Book (1605), Monteverdi goes even further, adding for the first time an instrumental basso continuo part to the five vocal parts. This allows for greater contrasts, for example by contrasting passages sung by one voice with only basso continuo with passages for the whole ensemble. In the Sixth Book (1614), as noted earlier, we find a five-part arrangement of the ‘lamento d’Arianna.’ In the Seventh Book (1619) and Eighth Book (1638), the step from the Renaissance to the early Baroque is fully made. Or rather, here the refined musical techniques of the Renaissance—called by Monteverdi the prima pratica (the first practice or the first style)—are enriched by the new expressive possibilities of the early Baroque style (the seconda pratica, also described by Monteverdi as the “Perfettione della moderna musica”).

Monteverdi also works wonders in the field of church music. To observe this, one only has to look at the edition of his ‘old-fashioned’ six-part Mass setting and the revolutionary Vespro della Beata Vergine (Venice, 1610), known in the English-speaking world as the Vespers of the Blessed Virgin. The message Monteverdi wants to deliver is clear: I master all techniques and styles, from the most learned ‘stile antico’ to the most modern styles. Not surprisingly, a contemporary described him as “the greatest composer in Italy.” As far as I am concerned, he could have added: “of all time.”

For his recording of L’Orfeo, Argentine harpsichordist and conductor Leonardo García Alarcón had at his disposal splendid vocal soloists he knows through and through, as well as his own Chamber Choir of Namur and the Cappella Mediterranea he founded. The result is unforgettable. García Alarcón’s countryman Gabriel Garrido conducted a delightful recording of the Vespers of the Blessed Virgin (K617). The same work was recorded live by John Eliot Gardiner in the Venetian San Marco in 1989, which is actually a pity as this beautiful church has difficult acoustics, which does not help the clarity of sound. Still, this CD box is worth buying, as Gardiner also recorded the alternative six-part version (with only organ accompaniment) of the seven-part Magnificat. That ‘encore’ was recorded separately at London’s All Saints’ Church and sounds absolutely magnificent. The aforementioned Gabriel Garrido also made great recordings of Monteverdi’s three surviving operas.

This essay is the second in a series entitled “Vivaldi and Others” by Kees Vlaardingerbroek.