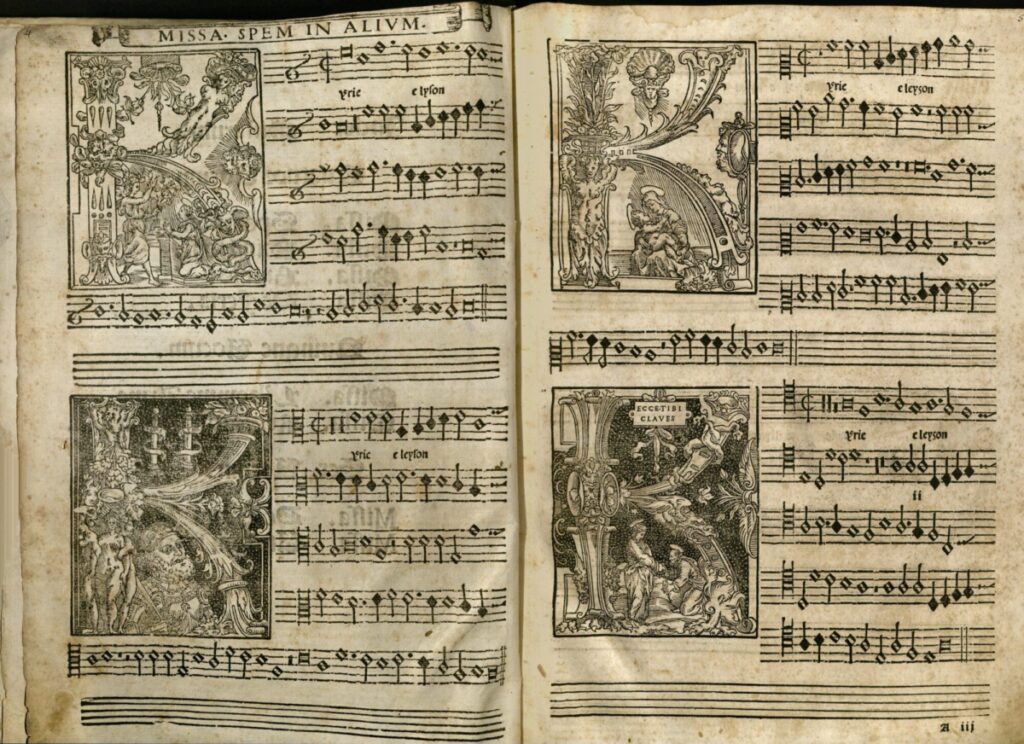

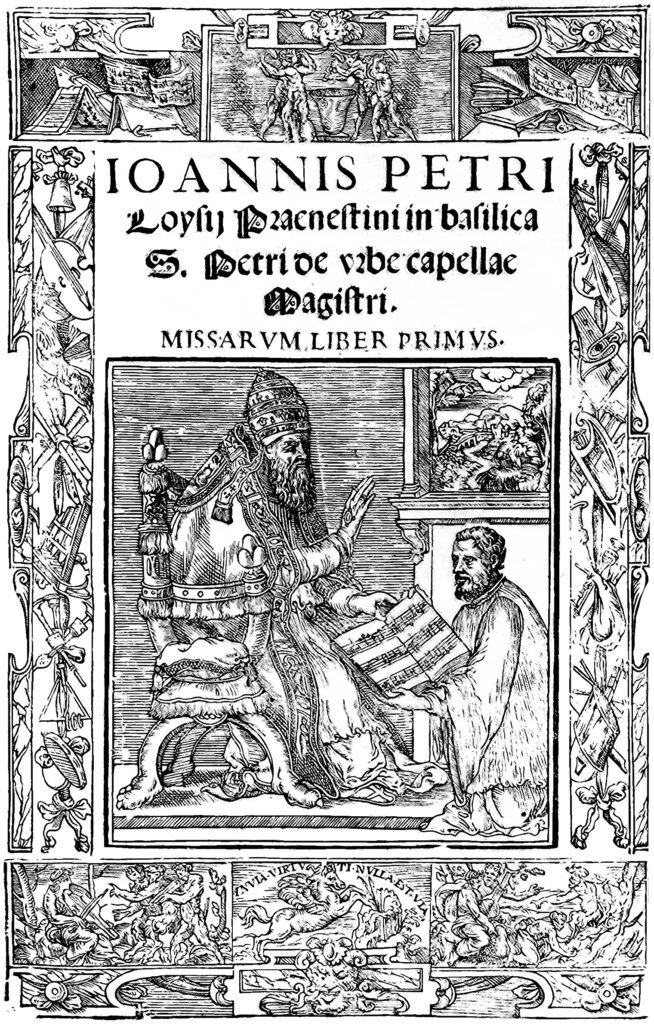

Leaves A2v-A3r, Ioannis Petraloysii Praenestini Missarum Liber Tertius, by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, John J. Burns Library, Boston College.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

I must have been 5 or 6 years old when I discovered my parents’ record collection. A mysterious and deeply fascinating world opened up to me. Not always to my parents’ delight, by the way, because I was not exactly gentle with all those expensive LPs and singles. But the temptation was simply too great, and no warning or prohibition could keep me away: I had to return to those beautiful LP covers, often with brilliant reproductions of historical paintings or photographs of Italian cityscapes on the front, within which were encased those black discs with their beautifully shiny surfaces and magical grooves! And all those names that so captured my imagination and that I could hardly read, let alone pronounce correctly! It was wonderful to put those subtle discs on the record player, put the needle on, experience that hypnotic spinning motion and then … those mysterious and seductive sounds. I often found such an LP far too long and the music far too difficult, yet I felt I had discovered a fairy world—a world that was actually the real world—and that I needed to explore. A single with a flute concerto by a certain Vivaldi (the name alone was music to my ears!) was my favorite. I heard a flute player imitating birdsong and thought it was even more beautiful than the actual birdsong in our garden. “I Musici” was the name of the orchestra. My father said that was Italian for ‘the musicians,’ but to my ears that Italian name really sounded much better. And what a sound that small ensemble of twelve musicians produced! But I also found to be irresistible the recordings of ancient Italian music with the Dutch violinist Herman Krebbers and the Amsterdam Chamber Orchestra (conducted by André Rieu Sr.). Slowly but surely the conviction grew in me that Italy had to be heaven on earth.

Now, more than half a century later, it actually still feels that way. Although, as I got older, Italian composers have had to tolerate the great German composers alongside (and sometimes even above) them, unknown Italian names still instantly make me extra curious. When I am in Italy, I continue to have the feeling of living more intensely than in any other country: the food tastes better, the cities are more beautiful, and the people livelier.

While staying in my old university town of Bologna in the summer of 2022, I suddenly got the idea for this series of essays. By writing about my favorite Italian composers, placing the greatest Italian masterpieces in their historical context and listing the finest performances known to me, I hope to pass on the best of myself as a music scholar and concert organizer to an interested audience. Moreover, I want to convey something of my lifelong love and fascination for Italian music. Not all periods interest me equally; the selection is personal and may seem arbitrary in other people’s eyes. I begin our journey with Renaissance composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, not because there were no brilliant composers before him, but simply because I know too little about medieval Italian composers. Should these essays serve as signposts for the novice listener, and entertaining reading for the connoisseur, then I will have succeeded in my aim.

I would like to conclude this introduction with a line from the foreword that Domenico Scarlatti wrote for his Essercizi per gravicembalo published in London in 1738: “Reader, show more of your human than of your critical side, and thereby only increase your own pleasure.”

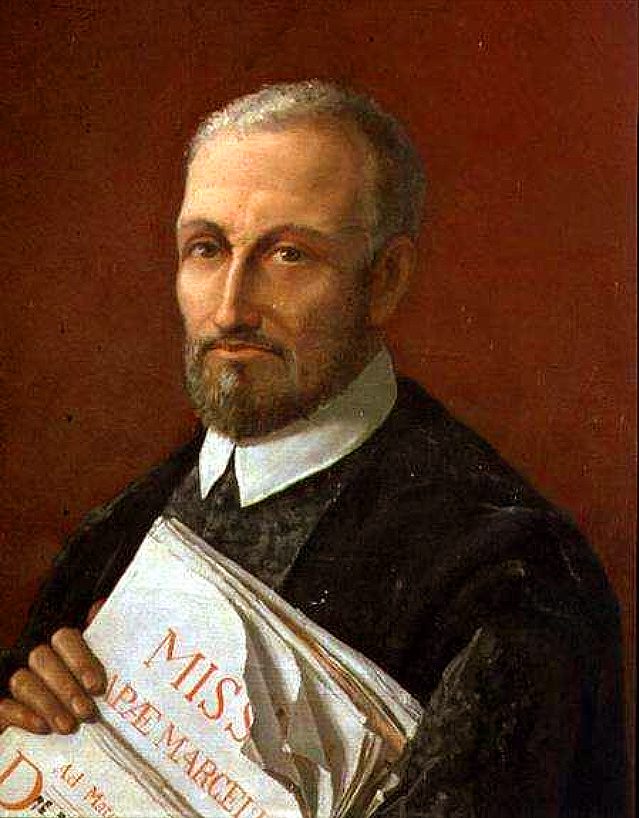

The truth is that in the course of time composers sinned against the truly religious spirit … [and] Pope Marcellus would have completely abolished church music. Fortunately, Giovanni Palestrina recognized that the fault for this lay with the composers and not with the art of music itself. For this reason, on that occasion he composed the Mass entitled Papae Marcelli …

Adriano Banchieri, Conclusioni nel suono dell’organo, Bologna, 1609, p. 18.

The 16th century was a century of endless religious disputes and wars. It was also the century of the ‘Revolt of The Netherlands,’ which would eventually result in the creation of the Republic of the Seven United Provinces in 1588. Philip II (1527-1598), the devout Roman Catholic king of Spain, continued to oppose Dutch independence and, until his death, fought the Protestants by any means necessary.

Philip II may have a bad name among the Dutch, but he was certainly a great lover of art and music. For this reason, the Italian composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525 or 1526-1594) dedicated his Missarum liber secundus (‘Second Mass Book’), a collection of seven Masses, to the Spanish king in 1567. Apparently, the composer was richly rewarded for this, because three years later Palestrina also dedicated his Missarum liber tertius (‘Third Mass Book’), also consisting of seven Masses, to Philip II.

Philip II was one of the pillars of the Counter-Reformation, the period from roughly 1550 to 1650 in which the Catholic Church sought to preserve what it still possessed and regain what it had lost to the Protestants. The Church was aware that it could succeed only if its doctrine was more precisely defined and the many abuses within the Church were harshly combated. In the Northern Italian city of Trento (‘Trent’), the Concilium Tridentinum (‘Council of Trent’) was organized for this reason. In the years 1562 and ’63, several times in Trent attention was paid to abuses in church music. It was often said to be too worldly and seductive. Also, the sacred texts would often be completely unintelligible because the vocal parts recited the words too independently from each other. Voices arose that wanted to banish all this complicated polyphonic music from the Church and retain only the traditional monophonic Gregorian chants.

This puritanical attitude was opposed first of all by musicians who saw their livelihood threatened, but also by nobles and clergy who feared a loss of decorum. The Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand I even wrote that he considered music “a divine gift” that should never be banned from church services. Other proponents of polyphonic church music pointed out that music promoted church attendance, not only among faithful Catholics, but also among non-believers, dissidents, and Protestants. Was this not absolute proof that the Church could not do without rich church music?

In order to take the wind out of the sails of the opponents of rich polyphonic church music, Palestrina is said to have composed the Mass which after its publication in 1567 in the Second Mass Book became famous under the title Missa Papae Marcelli (‘The Mass of Pope Marcellus’). With this Mass, Palestrina is said to have wanted to dispel all doubts on the part of church leaders, composing an ‘exemplary’ Mass that had nothing worldly about it and in which the liturgical words would always be clearly audible—even though Palestrina composed this work for as many as six independent vocal parts. This theory also seems to be borne out by the fact that Palestrina did not use existing secular melodies in the Missa Papae Marcelli, as often happened at the time. The fact that some melodic motifs in the Mass bear some resemblance to the then-famous song L’homme armé is probably coincidental. Moreover, in the Gloria and the Credo of the Missa Papae Marcelli, Palestrina deliberately used a much simpler style than in the other sections of the Mass (Kyrie, Sanctus and Agnus Dei): after all, the Gloria and the Credo contain many more words than the other three sections of the Mass, and so the danger of unintelligibility always lurks if the composer were to make use of all kinds of complex musical techniques in those sections of the Mass as well. Simple where it must be, and complex where it can be, seems to have been Palestrina’s motto.

The story has been both defended and criticized down the centuries. I myself used to think it was first and foremost an amusing anecdote, the kind of story about which Italians say ‘se non è vero, è ben trovato’ (‘if it’s not true, it’s well invented’). And I was pleased to learn that the mythical ‘saviour of church music’ inspired German composer Hans Pfitzner to write his greatest masterpiece, the opera Palestrina, in the years 1912-’15. These days I am a little less skeptical. Indeed, Pope Marcellus II, who lived from 1501-’55, seems to have paid much attention to the improvement of church music throughout his career. If Palestrina wrote this Mass to convince Pope Marcellus II that polyphonic church music could be composed in such a way that nothing objectionable could be found in it, then it must have been in April 1555, since Marcellus occupied the papal chair for only 22 days—from April 9 to May 1, 1555. Should the old story be true, that Palestrina wrote his Mass setting to convince the Council of Trent, then the work must have been composed in 1562 or 1563, since church music was critically scrutinized several times in those years. In the latter case, the title of the work is historically confusing because Pope Marcellus II had been dead for more than seven years by then. It is not inconceivable, that Palestrina indeed composed the Mass in 1562 or 1563 and dedicated it to the memory of Marcellus II.

Be that as it may, Palestrina’s Missa Papae Marcelli gained canonical status soon after the composer’s death. Numerous theorists saw in this Mass in particular the embodiment of the true church music style. Consequently, many Roman Catholic composers imitated Palestrina’s serene, thoughtful, and harmonious composition style in their own church music. It seems that Palestrina himself consciously pursued this exemplary style during his lifetime. Not surprisingly, the Missa Papae Marcelli was published in the Second Mass Book, which Palestrina dedicated to Philip II, the most powerful Roman Catholic monarch of his day, with a title chosen by the composer himself indicating papal, i.e. supreme, ecclesiastical approval. Palestrina clearly knew how to win over the greats of his day like no other composer of his time.

Technically perfect, but also somewhat lifeless, art (‘ars perfecta’): that is the impression of Palestrina’s music the reader might get while reading the above. Yet life is always stronger than doctrine, even with Palestrina. In the second Agnus Dei section from the Missa Papae Marcelli, ‘forbidden’ parallel octaves occur between the alto part and the first bass part. I suspect that Palestrina may well have seen this ‘impurity,’ but that he rightly considered this irregularity to be hardly audible, if at all, in the six-part fabric.

After Palestrina’s death, his reputation took on mythical proportions. Anyone who wanted to be taken seriously as a composer of church music had to be able to write flawlessly in Palestrina’s style. But fewer and fewer composers and musicians could read 16th century musical notation properly, which is why special manuals were put on the market. Some now forgotten composers working in 17th century Rome, like Domenico Dal Pane and Matteo Simonelli, sometimes used Palestrina’s ‘exquisite motets’ (‘esquisiti motetti’) as the basis for their Masses. But even these faithful followers of Palestrina also wrote ‘modern’ church music in which the new means of operatic expression were combined with the old tried and tested polyphonic techniques. We also see this ‘multilingualism’ in composers such as Claudio Monteverdi, Alessandro Scarlatti, and Antonio Lotti. Yet the admiration for Palestrina was not shared by all. The renowned church composer Giuseppe Ottavio Pitoni (1657-1743) studied Palestrina’s works in depth, but preferred the church music of Orazio Benevoli (1605-1672).

Remarkably, the priest-composer Antonio Vivaldi seems to have had even a certain aversion to the ‘old style’ (‘stile antico’) à la Palestrina: it is certainly no coincidence that for the concluding fugues in his Gloria RV 588 and his Gloria RV 589, he adapted a strict fugue by his older Venetian contemporary Giovanni Maria Ruggieri (c. 1669-1714). What a difference from his fellow townsman Francesco Antonio Calegari (1656-1742), who admired Palestrina and other 16th century masters to such an extent that he sometimes tore up his own works out of desperation!

In 1725, the ‘Austrian Palestrina’ Johann Josef Fux (1660-1741) published his immensely influential textbook Gradus ad Parnassum. The second part of this book was written in the form of a dialogue between Master Aloysius, who claims to voice Palestrina’s views, and his pupil Josephus, who represents Fux himself. Bach owned a copy of Gradus ad Parnassum, while Haydn and Beethoven studied the book in depth. In the 19th century, Palestrina’s church music would so overwhelmingly define the picture of what true church music should sound like that many composers of church music who did not conform to the 16th century master’s example could count on rejection or even a ban. A well-known example from Dutch music history is the impressive Mass for tenor, male choir and organ by Alphons Diepenbrock, which was published in 1895, but the first liturgical performance of which did not take place until 1916. At a time when the Roman Catholic church composers in particular were producing one slavish Palestrina imitation after another, there was hardly any sympathy for Diepenbrock’s efforts to enrich the Palestrina style with the expressiveness of Wagner’s late-Romantic harmony.

After World War II, the rapidly spreading secularization in the West not only had disastrous consequences for the Catholic Church itself, but also for Palestrina, the great representative of its church music. The fact that the Second Vatican Council allowed Mass to be celebrated in the vernacular certainly did not help the spread of Palestrina’s Latin church music. As a result, Palestrina’s music increasingly disappeared from view, only to play an extremely marginal role in musical life today. It is my sad but inescapable conclusion that Palestrina is now a neglected treasure, one to be rediscovered.

Several fine recordings of the Missa Papae Marcelli are available. Somewhat ‘romantic’ and slow, but at the same time very atmospheric is the performance by Pro Cantione Antiqua conducted by Mark Brown, recorded in early 1987 in the wonderfully spacious acoustics of St. Alban’s Church in London (IMP Classics). Tighter, more agile and ‘modern’ is the fine recording by Oxford Camerata, conducted by Jeremy Summerly (Naxos). For those who would like to hear music by Palestrina from the liturgical calendar, there are the Books of Lamentations (‘Lamentationes’) for Holy Week. The Second Book was beautifully recorded a few years ago by the vocal ensemble Cinquecento (Hyperion).

This essay is the first in a series entitled “Vivaldi and Others” by Kees Vlaardingerbroek.