Giacomo Puccini at his piano, 1900

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Elvira says she is going away, but never actually leaves. I would like to stay here alone too. I would work and go hunting. But where will I go when I leave here? And how will I spend my life then? I am now used to the convenience of my own home! In short: my entire existence is an agony! I work, but not as I would have liked.

—Giacomo Puccini in a letter to Sybil Seligman, dated the 5th of January 1909.

Sometimes a piece of music touches us so deeply that we cannot even imagine that its composer was not an extremely honorable and sensitive human being. Take Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924). Can you think of a composer who painted more poignant musical portraits of humiliated and suffering women than he? Think of the singer Floria Tosca, who goes to extremes to save her lover; or Sister Angelica, the nun, who, during a lightning visit from her ice-cold aunt, learns out of the blue that her illegitimate son has already died two years ago from the effects of high fever; or Cio-Cio-San, nicknamed Butterfly, the Japanese child-woman who gives up her baby to her manipulative and unfaithful American lover. For these and a whole host of other female characters in his operas, Giacomo Puccini composed music that pierces the soul.

The composer had this fascination with women in real life too. In literature, he has even been called an obsessive seducer. Puccini seems to have sought emotional support as well as sexual satisfaction from women. But especially in crisis situations, he could show his worst side. One extraordinarily painful story concerns Dori Manfredi, the young woman employed by the Puccinis. Giacomo’s eternally jealous wife Elvira Gemignani was so convinced that Dori was having an affair with her husband that she sent her away and publicly portrayed her as a whore. The poor girl could not bear the shame and poisoned herself. Her agony lasted for several days until she finally died. Afterwards, an autopsy was done on her body at the request of her family, which conclusively established that Dori was a virgin. The result was a high-profile trial, which resulted in Elvira being sentenced to a heavy prison term. Puccini had already fled to Rome at the first signs of trouble and had not lifted a finger to prevent this tragedy. Through large-scale bribery, Puccini eventually managed to keep his wife out of prison, but the marriage would never fully recover.

In political matters, too, Puccini often gave the impression of being a very indecisive character. A few years before his death, under pressure from his wife and a circle of friends, he finally accepted membership of the fascist party. Already as a young man, Puccini always liked to complain about the political disorder in his own country and believed that only a strong leader could offer a solution. In July 1920, he wrote to his friend Gilda dalla Rizza: “Here everything is rotten, we live badly, without order, without any protection by the state … How I feel like living abroad!” After the March on Rome (27-29th of October, 1922), Puccini was hopeful: “And Mussolini? Hopefully he is what is needed! Let him come if he will renew [Italy] and give some peace to our country.” In 1924, the year of his death, Puccini wrote that he had no faith in democracy because “I do not believe in the possibility of educating the masses.” Puccini, incidentally, would only meet Mussolini in person once. He wanted to present ‘the Duce’ with a plan for a national theatre, but received the blunt response, that there was no money for it. Discouraged, Puccini then did not dare broach another plan he wanted to submit to Mussolini.

As the above shows, Puccini was a complex man with a distinctly dark side. This is also reflected in almost all his operas. Le Villi and Edgar already contain much poignant music, but especially from Manon Lescaut (1893) onwards, there is a small but extraordinarily high-quality oeuvre of seven overwhelming operas (or nine, if one counts the three titles of Il Trittico separately). In this figure I have not included La rondine, Puccini’s only foray into operetta, which was not a complete success. Moreover, Puccini’s last opera, Turandot, was left unfinished when the composer succumbed to throat cancer in Brussels on the 29th of November 1924.

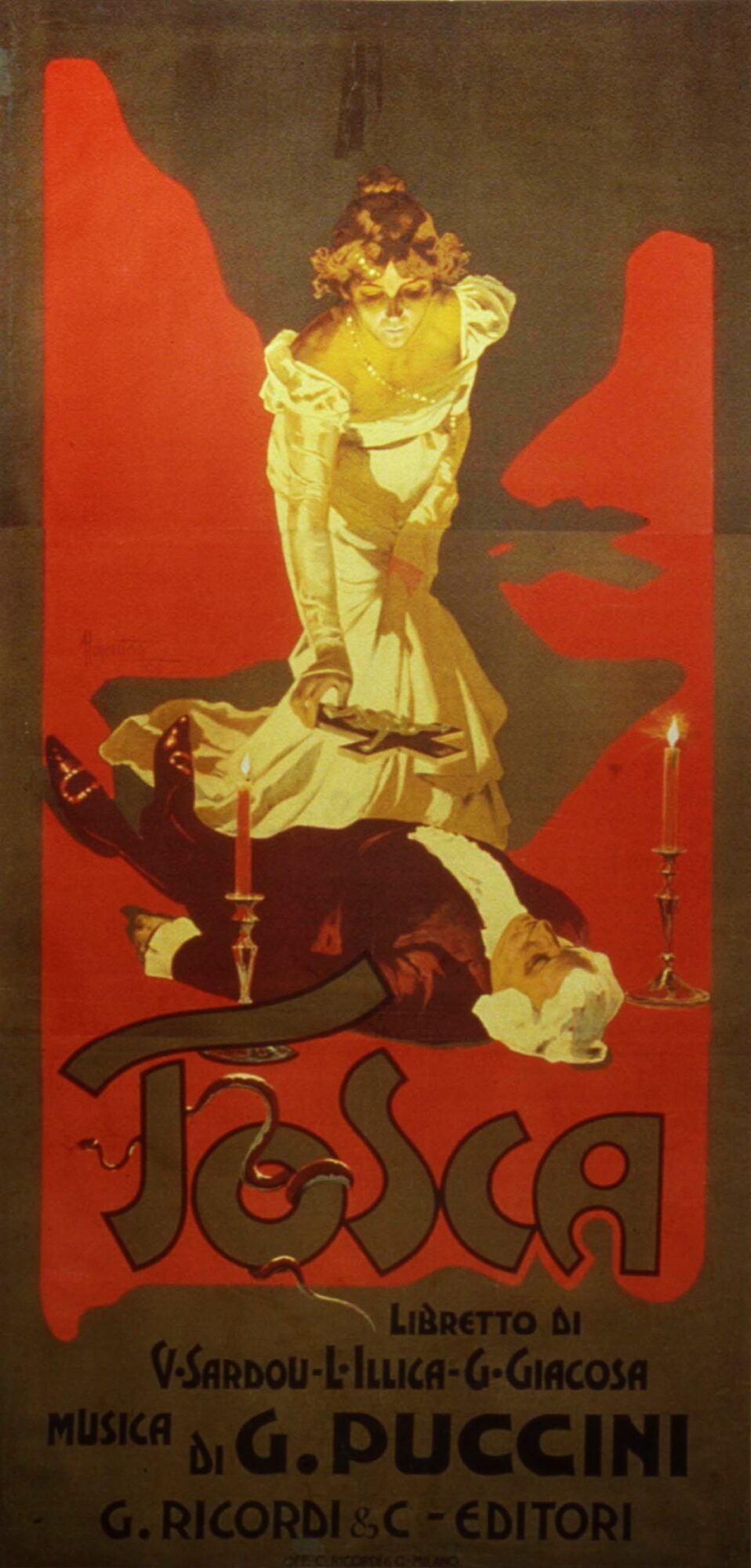

Tosca, composed between mid-1896 and late September 1899, and first performed at the Roman Teatro Costanzi on the 14th of January 1900, may not be Puccini’s most convincing opera, but it is nonetheless my favourite. The third act in particular has often been criticised, especially for the fact that Baron Vitellio Scarpia, commissioner of police and the embodiment of Absolute Evil, whose personality had given so much dramatic relief to the first two acts, is no longer alive in the third act. True, the spirit of the debauched and cynical baron is still palpable in the third act: Scarpia’s diabolical plan of a mock execution that is in reality a real execution ends exactly as planned in the death of Tosca’s lover, the young painter Mario Cavaradossi. But Scarpia himself is no longer there to sing of his triumph in ecstatic terms. All the better, the reader might object, we can do without that! An understandable reaction. But paradoxically and perversely, in the first two acts of Tosca, we spectators are so captivated by Scarpia’s sadistic personality that we collectively fall prey to Stockholm syndrome, as it were, and hardly want to miss the tyrant in the third act. It says something about the dark sides of Puccini himself and his impressive ability to express the darker sides of the human soul in the most intoxicating music. And it undoubtedly says something about us, too. If my memory does not deceive me, I felt this sharply as a young boy. We had a single at home, on which Italian tenor Carlo Bergonzi sings Cavaradossi’s aria “E lucevan le stelle” from the third act. Such stirring music, so perfectly sung, was an unprecedented emotional rollercoaster for me. But after listening to the single breathlessly four or five times in a row, I then fled quickly back to the safer world of the masters of the Italian Baroque.

The opera’s libretto is based on the drama La Tosca (1887) by French playwright Victorien Sardou. Soon after the play’s premiere, Luigi Illica had set to work distilling an opera libretto from it for Puccini’s friend and fellow composer Alberto Franchetti. After Franchetti had already started setting the libretto to music in 1894, Illica and Puccini’s publisher managed to persuade Franchetti to abandon the project. This paved the way for Puccini, for whom Illica wrote a new version of the libretto in collaboration with Giuseppe Giacosa. Hearing of this, Franchetti felt deeply cheated and ended his friendship with Puccini.

Where and when Tosca takes place had already been precisely indicated by Sardou: the entire action takes place on the afternoon, evening, and night of the 17th of June 1800. So, within a time span of less than 18 hours, all three main characters perish. We are also told which locations in Rome form the background to the action: the first act takes place in the church of Sant’Andrea della Valle, where Mario Cavaradossi is working on a painting of Saint Mary Magdalene; the second act in the Palazzo Farnese, where Scarpia is staying on the first floor and where, downstairs in the queen’s ballroom, the alleged victory over Napoleon is celebrated; and the third act in the Castel Sant’Angelo, which for centuries has served as a prison, among other things. Puccini also paid great attention to all kinds of historical details. For instance, he researched the tuning of the bells of St. Peter’s to make the morning bells that are rung at the beginning of the third act sound as authentic as possible. He also inquired from a clergyman friend to which liturgical melody the Te Deum was sung in Rome. It characterises the careful and thorough way Puccini worked, which had little to do with the old Italian tradition, in which a composer was supposed to be able to write a new opera within a few months if necessary.

It is not possible in this context to do justice to the unlimited musical ability Puccini displays in this score. Let me suffice with a few remarks about the second act. Towards the beginning of it, Scarpia stands at an open window in his study and Tosca’s singing reaches him from the ballroom. When the celebratory cantata is over, he has Tosca come upstairs, while he has her lover Mario tortured in an adjoining room. Heavily affected by Mario’s screams, Tosca ceases her resistance and promises, in desperation, to give herself to Scarpia. But before it comes to that, she ends his life with a knife. The second act ends with Tosca’s chilling words: “And before him all Rome trembled!” How Puccini repeatedly ratchets up the dramatic tension in the second act, and in between also manages to put Tosca’s brilliant nostalgic aria ‘Vissi d’arte, vissi d’amore’ (‘I lived for art, I lived for love’) into Tosca’s mouth, it borders on the unimaginable.

Recommended recordings

I would like to mention here two legendary recordings of Tosca: the studio recording made by Maria Callas with conductor Victor de Sabata in 1953 (Columbia Records/EMI) and Leontine Price’s with Herbert von Karajan (Decca, 1962).