“The Concert,” a 111.3 cm x 152.4 cm oil on canvas by Carl Schweninger jr. (1854-1903).

I am completely smitten with Viotti’s Violin Concerto in A minor […]. It’s a fantastic piece, showing remarkable freedom of invention. It sounds like he is improvising and everything is masterfully conceived and designed. […] The fact that people generally don’t understand and don’t respect the very best pieces—i.e. Mozart’s solo concertos and Viotti’s concerto mentioned above—is what allows someone like me to thrive and achieve fame.

Johannes Brahms, letter of 21 June 1878 to Clara Schumann.

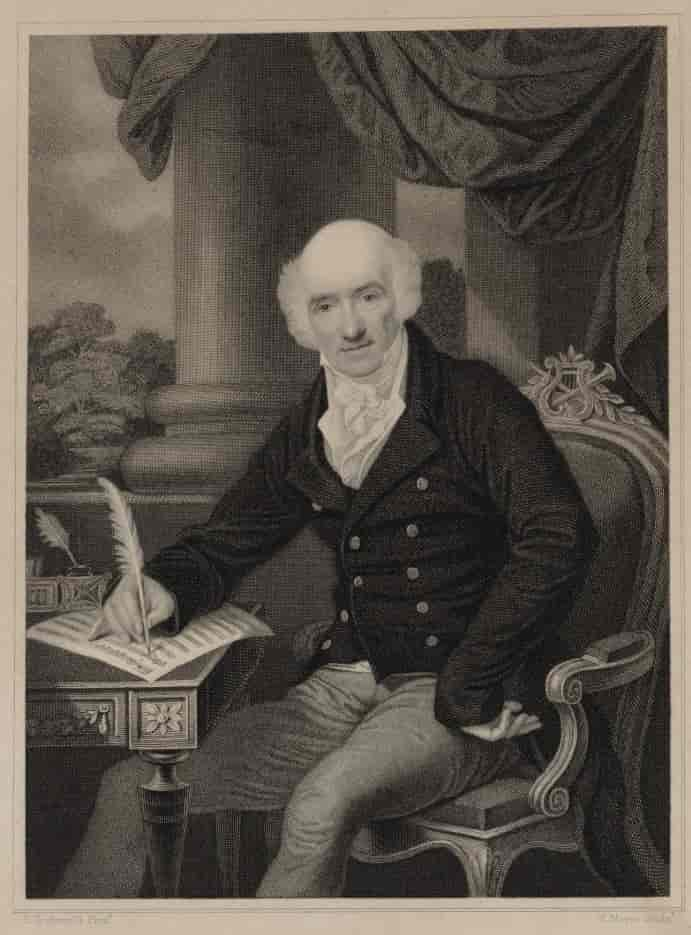

Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755-1824), yet another Italian name that means very little to music lovers these days. And yet, during his lifetime he was internationally renowned as a violinist, violin teacher, and composer. Viotti studied in Turin with the famous violinist and composer Gaetano Pugnani (1731-1798), with whom he made long concert tours throughout Europe. In 1784, we find him at the French court. After the French Revolution, he exchanged Paris for London, where he earned huge sums of money and also worked closely for a time with the Austrian composer Joseph Haydn, then also residing in London. Viotti’s playing, according to a contemporary, is characterised by “a powerful, full tone, indescribable ease, purity, precision, shadow and light, combined with the most charming simplicity.”

In February 1798, Viotti was forced to leave London because the British government suspected him of revolutionary sympathies. A few years later, he was allowed to return to the English capital, but from then on, music played second fiddle in his life and Viotti devoted himself mainly to the wine trade. In private circles, however, he still performed and was considered the most important violinist of his time. On the 1st of November 1819, Viotti was appointed director of the Paris Opéra, a prestigious position he managed to hold for only two years. Deep in debt, he died a few years later in London.

Apart from a few separate arias, Viotti left only instrumental music. At the heart of his oeuvre are no fewer than 29 violin concertos. Especially in the last ten, composed in London, Viotti manages to strike a brilliant balance between infectious virtuosity and musical depth. In these works, he pays more care to the role of the orchestra than he had previously done in Paris, possibly influenced by his recent experiences with Haydn’s ‘London’ symphonies.

After Viotti’s death, some of his late violin concertos continued to hold repertoire for a long time, although it is notable that some new editions of them seem to have served mainly pedagogical purposes. In fact, this has remained true to this day. For baroque violinists, this repertoire is ‘too late’—and often too difficult to play—while most star violinists of our time mistakenly see ‘practice material’ in it. And so, these wonderful violin concertos fall ‘between the shore and the ship,’ as the Dutch saying goes.

Admittedly, the Violin Concerto No. 22 in A minor, composed around 1795, has never quite disappeared from the concert programmes. We probably owe that not only to Brahms (see the quote above), but also to Brahms’s friend Joseph Joachim, the celebrated violin virtuoso who loved to perform Viotti’s concerto and also made a new edition of it. Right away, the orchestral introduction to the first movement with its 80 bars full of passionate melodies and expressive harmonies, makes it clear that this Violin Concerto No. 22 opens the doors to the Romantic violin concerto. What is also ground-breaking is that in the third movement, Viotti not only writes out the (normally improvised) cadenza for the solo instrument himself, but also has the orchestra accompany that cadenza. That example was to be widely emulated in the 19th century. Viotti’s Violin Concerto No. 22 would even leave musical traces in Brahms’ own Violin Concerto (1878) and in the first movement of his Concerto for violin and cello (1887), works written more than 80 years after Viotti’s concerto.

It is about time Viotti’s violin concertos are finally played more often in the concert hall, performed by the great violinists who are a conditio sine qua non for this repertoire. And that certainly applies not only to the impressive Violin Concerto No. 22. But I know from personal experience that the old prejudice that Italy has produced little of interest in the field of instrumental music after the generation of Vivaldi and Tartini still reigns supreme. It often takes a lot of time and patience to convince violinists that when it comes to violin concertos, the second half of the 18th century has more to offer than Mozart’s five delightful concertos.

I am convinced that eventually, Viotti’s best violin concertos will get the attention they deserve. The beautiful melodies inspired by opera and bel canto, the compelling virtuosity of the solo part and the well-crafted instrumentation of these delightful works are too tempting to justify the unfair neglect of this repertoire any longer. Violinists of all countries, unite and take action!

A complete performance of Viotti’s 29 violin concertos has appeared on the label Dynamic, an undertaking which is especially interesting from a documentary point of view, but not completely convincing musically. Of the Violin Concerto No. 22, Itzhak Perlman’s performance—on an EMI CD with the telling title Concertos from my childhood—is too sentimental for me, too romantic in the bad sense of the word. Moreover, the accompanying orchestra is far below par. Rainer Kussmaul’s interpretation (cpo) is convincing stylistically, but it fails to captivate me. Still beautiful and compelling is the performance that Lola Bobesco released on record in 1980, which was also released on CD (Talent) nine years later, together with the equally beautiful Violin Concerto No. 23. In October 2023 the Finnish label Ondine issued a fine new recording of the Violin Concerto No. 22, with Christian Tetzlaff (violin) and the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin conducted by Paavo Järvi.