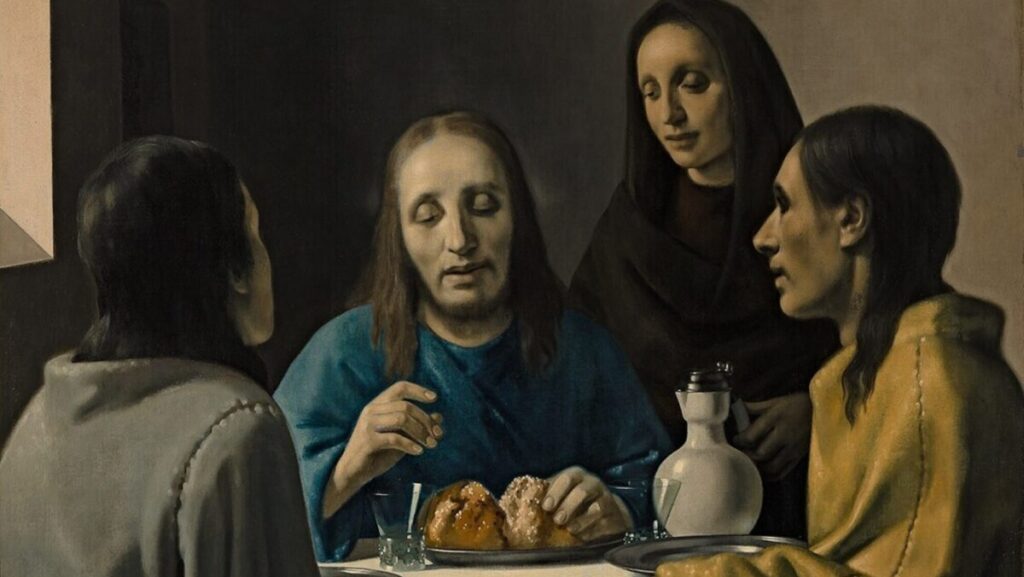

“De Emmaüsgangers,” (1937) by Han van Meegeren (1889-1947). In 1937, the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen was very pleased with the purchase of “The Supper at Emmaus,” a rare young Vermeer. Today the piece still hangs prominently in the museum, but under the name of Han van Meegeren (1889-1947). Van Meegeren was a master forger who cleverly responded to the desire of art historians to discover the missing link between the early and late work of Johannes Vermeer.

Not many people know that the ‘perfect forgery’ in painting, The Supper at Emmaus, has a musical counterpart: the so-called ‘Adagio by Albinoni.’ In 1937, master forger Han van Meegeren (1889-1947) painted a canvas in the style of the 17th century Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer, which he titled Emmausgangers, with the aim of proving that art critics were unable to distinguish spurious from authentic. When unexpectedly large sums were offered for the ‘Vermeer,’ Van Meegeren changed his tactics and decided to keep the deception a secret. Only after World War II did the truth come to light. What does this have to do with the so-called ‘Adagio by Albinoni’? To understand that, we must first turn the spotlight on Italian composer and musicologist Remo Giazotto (1910-1998).

Giazotto is best known for the books he published on Albinoni (1945) and Vivaldi (1965). Both studies contain a lot of valuable material, as well as a number of intriguing quotes from historical documents, which on closer examination seem to have completely vanished off the face of the earth. For this reason, Giazotto’s publications are often read with some caution or even distrust by musicologists today.

In 1958, Giazotto published his edition of an Adagio in G minor for strings and organ under Albinoni’s name. According to Giazotto, this was a reconstruction he had made on the basis of a bass part and some melodic fragments of an Adagio by Albinoni, which had supposedly been part of a multi-movement composition formerly kept in Dresden. Giazotto claimed that this composition had almost completely gone up in flames during the bombing of Dresden in February of 1945. However, even the fragments that were said to have survived the war proved completely untraceable to other researchers. For this reason, and because of the fact that the extremely sombre Adagio is stylistically very different from Albinoni’s demonstrably authentic works, the British musicologist Michael Talbot—the greatest authority on the Venetian composer’s life and work—concluded in 1990 that the Adagio in any case gives a totally distorted picture of Albinoni and his music. And it is not the first time in music history, by the way, that a composer’s fame rests mainly on a work that is not actually his: in the 19th century, almost the only piece of music known by Alessandro Stradella was the aria ‘Pietà, Signore,’ an aria that was actually composed in 1837 by the Swiss composer Louis Abraham de Niedermeyer.

But every disadvantage has its advantage, as goes Johan Cruijff’s famous saying. The worldwide popularity of the Adagio made more and more music lovers curious about the composer and his authentic works. In particular, the beautifully lilting oboe concertos from Albinoni’s Op. 7 (1715) and Op. 9 (1722) have rightly been performed frequently since the 1960s. But given that not even the ‘real’ Albinoni stands among my favourite Italian composers, for more information I refer to Michael Talbot’s book, Tomaso Albinoni: The Venetian Composer and His World (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990). And the Adagio? Well, that piece will certainly remain extremely popular as funeral music, whether it is indeed partly by Albinoni or—which is more likely—not at all.

The number of recordings of the Adagio is uncountable. The slowest and most solemn recording I know was made by the Berliner Philharmoniker conducted by Herbert von Karajan. While most performances last about seven minutes, Karajan manages to spread it to almost twelve minutes (DGG). A guilty pleasure indeed!