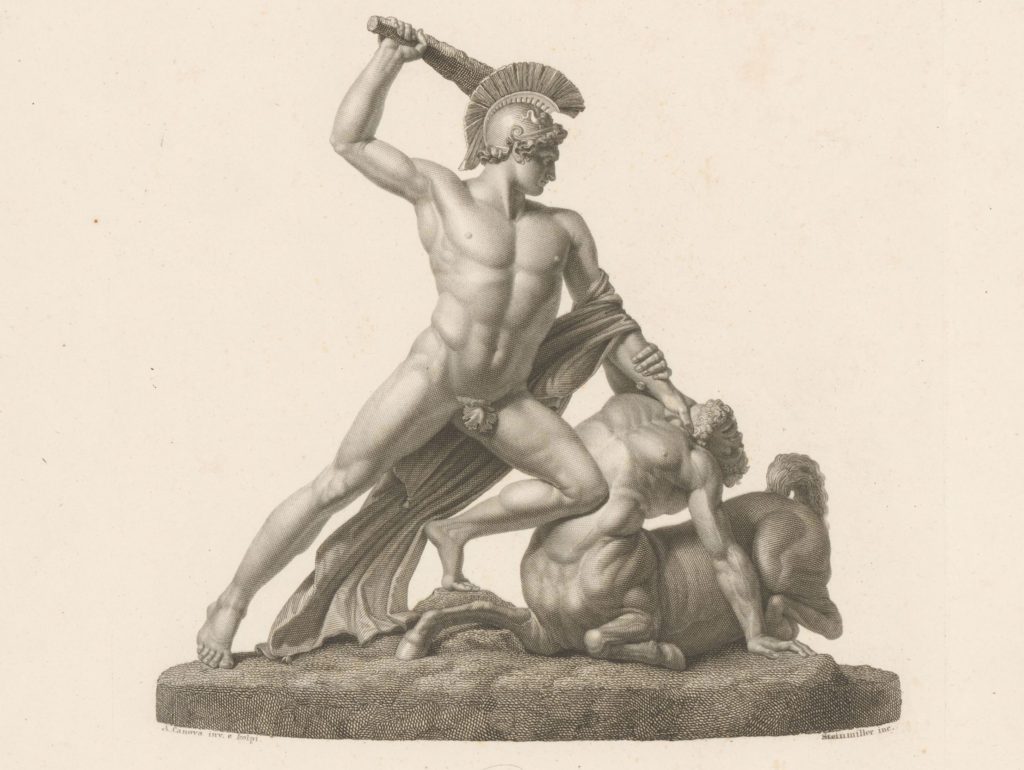

“Theseus and the Centaur” (1805-1841), a steel engraving by Joseph Steinmüller, after Antonio Canova’s sculpture in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Recently, a call to arms—metaphorically speaking—was issued by John Daniel Davidson in a piece published by The Federalist entitled “We Need To Stop Calling Ourselves Conservatives.” This piece was shared widely on social media and received much praise from the internet Right, and rightly so. I find little in the piece with which to disagree, and much to affirm. Nonetheless, I want to offer a defence of the word ‘conservative,’ which he argues we should renounce, and explain why I think we ought to keep using the term (and I think Davidson really thinks we should too).

Davidson begins with a list of how conservatives have failed to conserve much at all, and he remarks on how they have effectively lost the culture war. I don’t wholly disagree, but when one considers the ambitions of post-war liberals, progressives, socialists, and communists, who knows what the world would have looked like now had it not been for the relentless challenges launched by conservatives over the decades to slow the process of cultural revolution?

In any case, it does not follow from taking stock in the way that Davidson does that the conservative cause needs to be abandoned, or the name of that cause discarded. Spain, century after century, was conquered by a north African force that hated Christendom, the glories of which were so visible in Spain in particular. Eventually, the whole of Iberia was conquered but for the little kingdom of Castille. From there, however, the Reconquista began, eventually taking back the whole peninsula. Acknowledging failure can lead to action.

Of course conservatives should, as Davidson calls them to do, consider their unhappy situation. The ideology of progressivism that now dominates the West, which seeks to repudiate our civilisation and replace our shared life based on the common good with the chaos of competing appetites of isolated individuals, has conquered our nations and their noblest institutions. As Davidson says, conservatives must stop fantasising about 1980s-style market-based politics or libertarian small government settlements. They must, instead, instigate a Reconquista.

The argument from which Davidson derives the title of his piece seems one to which he himself is not committed. At one point Davidson says that conservatives need to stop calling themselves by that name and “start thinking of themselves as radicals, restorationists, and counterrevolutionaries.” He, however, does not adopt any of those denotations for the rest of his piece, remaining content to call conservatives conservatives. Perhaps this is because he sees that conservatism is already—quite organically—adopting the approaches to cultural, moral, and political discourse that terms like ‘radicality,’ ‘restoration,’ and ‘counterrevolution’ connote.

Take the word ‘radical.’ This word, as most know, etymologically means to return to the roots. Conservatives in the 1980s and ’90s—apart from a few eccentrics like Russell Kirk and Roger Scruton, at whom the Reaganites and Thatcherites always looked sideways—were not reading Edmund Burke. Well, conservatives today are reading him. In fact, they are reading many of those who led the counter-Enlightenment movement whence we get the word ‘conservative’: Burke, Maistre, Bonald, Chateaubriand, Donoso, Coleridge, Cobbett, Newman, Chesterton, Eliot, Kirk, Scruton, and so on. They are also reading Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, Seneca, Boethius, Augustine, and Aquinas. Having taken stock and acknowledged the colossal failure of conservatism to which Davidson refers at the beginning of his piece, conservatives are going back to the roots, discovering the principles of their social tradition and those who applied them in defence of their civilisation.

This is how ‘counterrevolution’ and ‘restoration’ begin. Returning to our roots in order to equip ourselves against revolution, for the sake of restoring what has been taken from us, is exactly what conservatism is all about. And the word conservatism itself is significant because it indicates that we are not simply protesting against something. Ours is not a negative creed, and in this way we are wholly different to our political, moral, and cultural adversaries who know of nothing but the impulse to repudiate. We affirm something. We affirm our civilisation and we want to conserve it. (As Scruton used to say, conservatism is—at the most fundamental level—about love).

The word ‘conservatism’ is important because, as I have indicated, it is bound up with a canon of thought. And that canon is one with which we should continue to familiarise ourselves if we are going to recapture what is rightfully ours, namely our civilisational inheritance. People on the Right who stray from that canon are routinely seduced by the unhinged esotericism of Julius Evola, Savitri Devi Mukherji, or the vast store of cod-Nietzschean neo-paganism out there in the blogosphere, whose material would be hilarious if it were not so corrupting of its readership.

Unforeseen dangers lurk, and it is plausible that they will reveal themselves too late for us to do anything about them if we abandon the term ‘conservative.’ Names are important, and the name ‘conservative’ is important if we are not to forget who we are and what we strive for.

A major theme of Davidson’s piece concerns the threat of new technologies, to which narrower ‘culture war’ issues remain secondary in his opinion. He believes that conservatism, or what it denotes, is unfit to address the dangers posed by such technologies. Again, I do not entirely dissent, but new technologies always shake the settled life of established societies. When the new technology of the printing press emerged, it was initially used to break up the religious unity of Christendom; thereafter, however, it became a major force for cultural and religious cohesion.

Social media and computer technology has been, no doubt, a colossal force for evil in the world, and has contributed in untold ways to the mass surveillance under which we must all now toil. It has also, however, made the finest books ever written instantly available to everyone, and thus made it possible for a low-wage earner to have a library at his fingertips that Samuel Johnson could only have dreamed of. To treat technology as if it couldn’t, with help from the coercive apparatus of a just and well-functioning State, be assumed by a conservative social order for the flourishing of its members is, I think, to underestimate its potential for the good.

I often place a particular quotation from Newman in my writing, because I think it is both the best and pithiest summary of the conservative cause I have ever read: conservatism is about finding “some way of uniting what is free in the new structure of society with what is authoritative in the old, without any base compromise with ‘progress’ and ‘liberalism.’” The challenge before us is that uniting the new technologies of the day with the moral law that has had authority over us throughout the course of our civilisation until our accursed age. Most philosophical classics, patristic works, and the whole Summa Theologica can be found on the internet, but so can the most abominable perversions known to man. A conservative social order would keep the former and ban access to the latter, and thereby unite what is free in the new with what was authoritative in the old.

Davidson proceeds to say that conservatives should want to be “wielding government power,” and that this “will mean a dramatic expansion of the criminal code.” Perhaps this is true, but conservatives have never believed that social transformation for the sake of the common good is exclusively obtained by coercion, even if law and its enforcement are a major component. Conservatives have always held that for the felicity of society—that it may not descend into political collapse (which is only ever a few bad decisions away)—interior transformation is required, namely virtue. Law does of course have a didactic dimension, but this aspect can only be expected to have the desired effect when it is supported by a broader culture that values virtue. The fact, then, that conservatism is becoming an increasingly religious social force is encouraging.

Interior transformation by the cultivation of virtue is becoming a major topic again in conservative thought. It is striking that, contrary to what people predicted only few decades ago, conservatism—especially among young people on the Right—is not redefining itself as a ‘secular cause for Western civilisation.’ Rather, it is becoming a deeply reactionary cause that is both aggressively political and profoundly religious.

Whether one looks at the NatCon guys or PostLibs on Davidson’s side of the Atlantic, or the Vanenburg or Radical Orthodoxy lot on this side, terms like ‘Christendom,’ ‘Integralism,’ and ‘religious identity’ are on everyone’s lips. Conservatives are rediscovering the need for public religion—true public religion—to bring about the civic virtue that is the prerequisite for conserving civilisation (which, after all, is the proper cause of conservatism). Davidson seems to recognise this phenomenon when he writes that to “talk of defending ‘religious freedom’ is to misapprehend that the real risk today is widespread irreligion.” In his concern here, however, he ought to feel completely at home with the conservatism that is rapidly becoming the mainstream of the Right.

Davidson says that conservatives need to give up their attachment to ‘small government’ and embrace political power to achieve their objectives. This strikes one as an attack on a straw man. True conservatives have never said otherwise and have always recognised the need for a robust, healthy State. What conservatives have insisted upon, traditionally, is that such a State need not be excessively centralised or unnecessarily intrusive on the lives of the citizenry, and that the best way to have a vigorous State that resists totalitarian tendencies is to arrange political power subsidiarily.

Sound-thinking conservatives, who have always believed that the market’s freedom must be balanced by paternalism for the sake of the common good, would readily agree with Davidson’s following recommendations for how political power might be used:

To stop Big Tech, for example, will require using antitrust powers to break up the largest Silicon Valley firms. To stop universities from spreading poisonous ideologies will require state legislatures to starve them of public funds. To stop the disintegration of the family might require reversing the travesty of no-fault divorce, combined with generous subsidies for families with small children. Conservatives need not shy away from making these arguments because they betray some cherished libertarian fantasy about free markets and small government.

Indeed, as he says, conservatives need not shy away from such arguments. If conservatives were more familiar with their own political and moral tradition, they would not shy away from these arguments but see them for what they are: conservative arguments. And conservatives need not disavow their own name of ‘conservative’ in order to embrace such arguments, but rather must reaffirm that to be conservative is to champion the cause of the common good—by direct political intervention if necessary.

Conservatives are now faced with a unique opportunity. Liberalism has made people miserable. The isolated individual pursuing his own appetitive impulses is a deeply unhappy person. The suicide rate in the West is a clear indication of this fact. In the UK alone, the leading cause of death for people aged 5-34 is suicide. The emancipation and personal flourishing promised by liberalism never arrived. By equating human flourishing with the commodification of everything, liberalism locked us up in our own selfish appetites, creating an epoch of chronic loneliness and misery.

This moment is a very special opportunity that conservatives would be foolish to miss. Perhaps in decades past, the conservative cause looked like an attempt to direct people back into a cage at the very moment they felt themselves emancipated. Now, however, people are crying out to be liberated from the fetters of self-indulgence and reclaim their ‘roots.’ They want to engage in a ‘values-based’ discourse, and it is in such a discourse that the conservative tradition can shine like a great beacon, leading people into the calm harbour of sanity. This, then, is a beautiful moment for a true conservative revival, but conservatives—calling themselves conservatives—need to wake up and seize it.