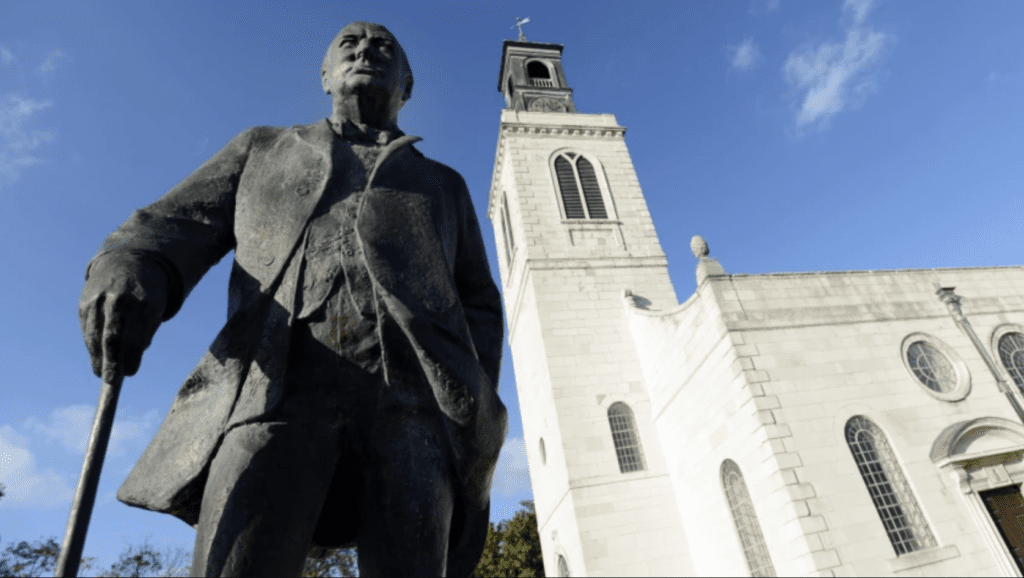

America’s National Churchill Museum (formerly the Winston Churchill Memorial and Library), is located on the Westminster College campus in Fulton, Missouri.

Fifty-seven years after his death, the cult of Winston Churchill shows no sign of flagging. At least sixty biographies were published by the end of the 20th century, and each passing year seems to bring a half dozen more. He is the subject of blockbuster Hollywood films (2011’s The Darkest Hour being the most recent) and new books that, astonishingly, manage to uncover fresh details (Erik Larson’s 2020 The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz being the best of the latest lot). Despite vigorous attempts to cancel him—statues of Churchill have been defaced and splashed with paint recently from Edmonton to London—he still looms large.

Churchill is now a mythical figure, and the number of those who remember him as a man is dwindling rapidly. I’ve spoken to only two: English author Os Guinness, who met him as a boy, and Churchill’s grandson, former MP Nicholas Soames, son of Mary Spencer-Churchill. Soames grew up at Chartwell and saw Churchill every day. “He was interested in everything we did,” Soames told me. “He came to watch us swim, he liked having his grandchildren around him.” He once slipped into Churchill’s bedroom, where he was reading a newspaper in bed. “Is it true that you’re the greatest living man, Grandad?” he asked. “Yes,” Churchill replied. “Now bugger off and leave me in peace.”

But in recent years, the Churchill myth has come under fire not only by progressives seeking to cancel anyone not born fifteen minutes ago, but also by conservatives. Columnist Peter Hitchens wrote in 2018 that it is “time we faced the unpalatable truth that Winston’s vanity and recklessness cost countless British lives and lost us our empire”—although he concedes that it is “[b]eyond doubt” that Churchill “saved Britain and probably the world when he rightly refused to parley with Hitler in 1940.”

Nevertheless, Hitchens believes that World War II has replaced Christianity as Great Britain’s reigning religion, with Churchill at the centre. “Instead of the triumphal ride into Jerusalem, the Last Supper, and the betrayal at Gethsemane, the Crucifixion and the Resurrection, we have a modern substitute: Winston the outcast prophet in the wilderness, living on cigars and champagne rather than locusts and wild honey, but slighted, exiled, and prophetic all the same.”

The Phoney Victory

Peter Hitchens

London: I.B. Tauris, 2018

In his 2018 book The Phoney Victory, Hitchens described the World War II religion he grew up with:

This war is the dominant theme of serious conversation, a source of metaphors and a frame of thought. It is also our moral guide, the origin of modern scripture about good and evil, courage and self-sacrifice … it is at Dunkirk and D-Day, or in the forests of Burma, or in the prisoner-of-war camps of Silesia or the Far East, where brave Britons of all classes defy their captors or in the freezing midnight clashes between escort ship and U-boat, that we find our lessons about how to be good and live well. The stories of the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son cannot compare with this. Even the Crucifixion grows pale and faint in the lurid light of air raids and great columns of burning oil at Dunkirk, a pillar of fire by night, a pillar of cloud by day.

One suspects that Churchill would not have objected to deification. “I am ready to meet my Maker,” he once blasphemously stated. “Whether my Maker is prepared for the ordeal of meeting me is another matter.” Churchill saw himself as a defender of Christendom, but not necessarily as a personal Christian. “I am not a pillar of the church, but a buttress—I support it from the outside,” he once said. And as Hitchens notes, some horrifying things were done by the Allies under Churchill’s leadership—the firebombing of Hamburg may have been code-named Operation Gomorrah, but the Lancasters raining hell on men, women, and children brought the thunder of Europe’s long-dead gods rather than the vengeance of the Almighty.

God and Churchill

Jonathan Sandys and Wallace Henley

Carol Stream, Illinois: Tyndale House, 2015

So what did the now-deified Churchill think of God and Christianity? It is a question that Churchill’s great-grandson Jonathan Sandys, who tragically died of lung disease at the age of 43, attempted to answer in his 2015 book God and Churchill, a fascinating albeit not particularly well-written scattershot analysis of Churchill’s spiritual beliefs. The book received harsh criticism from British historian Alistair Lexden, who insisted that Churchill was an agnostic and as proof quoted him as saying in the 1890s that, “Christianity will be put aside as the crutch which is no longer needed, and man will stand erect on the firm legs of reason.”

Lexden’s criticism, however, is based not on what Churchill actually believed but on his own apparent disdain for the idea that God works in history. It is not difficult for a Christian to accept that God used Winston Churchill to defend civilization, since Christians believe that His providence directs all things. But to an atheist or an agnostic, this idea is ridiculous. Lexden’s cherry-picked quote ignores many of his other statements and writings that reflect an evolution in his thinking, many of them made after that comment.

Churchill was introduced to Christianity not by his parents—who largely ignored him to pursue their own interests (including other romantic partners)—but by his nanny Elizabeth Everest, whose influence on Churchill was life-long. When he died at the age 90, a framed photo of her still stood beside his bed 70 years after her death. It was through her, Sandys suggests, that Churchill first began to treasure the Christian religion.

A closer look at Churchill’s life indicates that he took Christianity seriously, and perhaps sometimes even personally. This is precisely why, when Sandys was considering the project, he was urged by Churchill biographer Sir Martin Gilbert to start digging as there was “loads of information.” As early as 1897, for example, Churchill wrote that, “It is evident that Christianity, however degraded and distorted by cruelty and intolerance, must always exert a modifying influence on men’s passions, and protect them from the more violent forms of fanatical fever, as we are protected from smallpox by vaccination.”

And what, for example, would Lexden make of Churchill’s recounting of his escape from a Boer prison camp in 1899? While walking through South Africa, surrounded by enemies and unsure of where to turn, Churchill wrote:

I found no comfort in any of the philosophical ideas which some men parade in their hours of ease and strength and safety. They seemed only fair-weather friends. I realised with awful force that no exercise of my own feeble will and strength could save me from my enemies, and that without the assistance of that High Power which interferes in the eternal sequence of causes and effects more often than we are always prone to admit, I could never succeed. I prayed long and earnestly for help and guidance. My prayer, as it seems to me, was swiftly and wonderfully answered.

Churchill’s doubts vanished in that moment of prayer, confidence came to him, and he knocked on the door of the only house for twenty miles that would not have turned him in to his Boer captors. Later, he would experience many other close calls, including near-miraculous moments in the trenches of the Great War when he seemed to be called from the front lines at precisely the right moments. He became convinced that this was because God had a specific purpose for his life, and as prime minister, he told his worried bodyguard that nothing would happen to him as long as his task was before him. “The old man is very good to me,” he once noted gravely to Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe. “What old man?” asked his companion. “God,” Churchill replied.

He received similar comfort in 1911, when he was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty and was tormented by thoughts of Germany’s military buildup. He went to the large Bible that rested on his bedside table and flipped it open. His eyes fell on Deuteronomy 9, which begins with Moses addressing the fearful children of Israel in the wilderness:

Hear, O Israel: Thou art to pass over Jordan this day, to go in to possess nations greater and mightier than thyself, cities great and fenced up to heaven,

A people great and tall, the children of the Anakims, whom thou knowest, and of whom thou hast heard say, Who can stand before the children of Anak!

Understand therefore this day, that the Lord thy God is he which goeth over before thee; as a consuming fire he shall destroy them, and he shall bring them down before thy face: so shalt thou drive them out, and destroy them quickly, as the Lord hath said unto thee.

“It seemed,” Churchill said later, “a message full of reassurance.”

Churchill’s sense of his own destiny came from an event so unlikely that secular readers will be sure to scoff. It was a Sunday evening in 1891, and Churchill was only sixteen. He told his friend Murland de Grasse Evans that he saw great things in his future. “I can see vast changes coming over a now peaceful world,” he told his incredulous companion. “Great upheavals, terrible struggles; wars such as one cannot imagine; and I tell you London will be in danger—London will be attacked and I shall be very prominent in the defence of London.” Years later, when this all came to pass, Evans recalled the conversation with near disbelief.

Did Churchill believe in the truth of the Scriptures, or did he simply rely on them as a unifying cultural symbol and a repository of beautiful imagery with which to adorn his speeches? There seems some evidence, at least, that he saw the Bible as more than that. He not only referred to “the Impregnable Rock of Holy Scripture,” he also used the Bible as a source of personal comfort—when Franklin Delano Roosevelt warned Churchill that they could be targeted by the Luftwaffe if they met in Cairo, Churchill’s cabled response was succinct: “John 14:1-4.” The passage reads:

Let not your heart be troubled: ye believe in God, believe also in me. In my Father’s house are many mansions: if it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you. And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again, and receive you unto myself; that where I am, there ye may be also. And whither I go ye know, and the way ye know.

Regardless of whether Churchill was personally religious—most scholars believe the skepticism of his twenties lingered long—he certainly saw the world through a Judeo-Christian lens. Sandys lists dozens of examples of this. In a 1931 article in The Strand, Churchill noted “our duty to preserve the structure of humane, enlightened, Christian society.” During the Blitz, he referred to London as “this strong City of Refuge which enshrines the title-deeds of human progress and is of deep consequence to Christian Civilization.”

A year later, he stated that it “is no exaggeration to say that the future of the whole world and the hopes of a broadening civilisation founded upon Christian ethics depends on the relations between the British Empire or Commonwealth of Nations and the USA.” In 1946, he wrote down a list of objectives for the Conservative Party leadership—and the first point was: “To uphold the Christian religion and resist all attacks upon it.” As he once put it: “the more closely we follow the Sermon on the Mount, the more likely we are to succeed in our endeavours.”

Churchill was remarkably clear-eyed about the dangers of the soulless and secular statism promoted by everyone from the Bloomsbury elites to the twin barbarisms of Bolshevism and Nazism. “Our difficulties come from a mood of unwarrantable self-abasement into which we have been cast by a powerful section … of doctrines by a large proportion of our politicians,” he wrote in 1933. “But what have they to offer but a vague internationalism, a squalid materialism, and the promise of impossible Utopias?” He reiterated this sentiment in 1948, noting that England had entered a mood “encouraged by the race of degenerate intellectuals … who, when they wake up every morning have looked around upon the British inheritance, whatever it was, to see what they could find to demolish, undermine, or cast away.”

Indeed, it can be argued that it was Churchill’s understanding of the character of Christendom that made him a great man and gave him the insight to understand the threat Nazism posed. In a speech to the House of Commons in 1938 after the Munich Agreement, he thundered that “there can never be friendship between the British democracy and the Nazi power, that power which spurns Christian ethics, which cheers its onward course by a barbarous paganism.” This view of Christian ethics was not a mere convenience trotted out for political and polemical purposes—it was his sincere belief.

In a 1949 speech to scientists at MIT, he reiterated and expanded on his belief: “The flame of Christian ethics is still our highest guide. To guard it and cherish it is our first interest, both spiritually and materially. The fulfillment of spiritual duty in our daily life is vital to our survival. Only by bringing it into perfect application can we hope to solve for ourselves the problems of this world—and not of this world only.”

An anecdote recounted by Erik Larson in The Splendid and the Vile perfectly encapsulates how thoroughly Christianity permeated the great clash of civilizations. It was January 1941, and Churchill was desperately wooing Harry Hopkins, the man sent by FDR to gauge the situation in Great Britain. Churchill was eager to impress him with both Britain’s resilience and the necessity of American help. One night, a handful of men gathered in Glasgow’s Station Hotel, and several made speeches, including MP Tom Johnston, soon to be named secretary of state for Scotland. When Hopkins rose, he turned to Churchill.

“I suppose you wish to know what I am going to say to President Roosevelt on my return,” he said. “Well, I’m going to quote you one verse from that Book of Books in the truth of which Mr. Johnston’s mother and my own Scottish mother were brought up.” His voice dropped to a whisper, and he recited words from the Book of Ruth: “Whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge: thy people shall be my people, and thy God, my God.” He added his own words at the end: “Even to the end.” It was, Churchill’s doctor recalled, “like a rope thrown to a drowning man.” Churchill wept.

The Splendid and the Vile

Erik Larson

New York: Penguin Random House 2020

In the great struggles of the 20th century, Winston Churchill saw Christendom arrayed against threats from all sides—and became one of her greatest defenders. He believed in providence, in prayer, and his own destiny as divinely ordained—although his church attendance was generally limited to formal occasions. He felt a powerful emotional and spiritual connection with the Church of England, but rarely participated in her rituals. He believed that Christianity was the soul of the West and that Christian ethics were fundamental for her survival, but was less concerned about the immediate application of Scripture to his own life beyond his unshakeable belief that God wished to use him in some great way. As one historian glibly put it, Churchill seemed more sure that God believed in him than the other way around.

Sandys’ book presents a simple thesis: that God used Winston Churchill to save Christian civilization, and that Churchill himself believed this. Despite his hubris and his many mistakes, Churchill also knew that truly great men were not defined merely by military victory or political prowess. His secretary John Colville once recorded a conversation between Churchill and Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, who was a Christian. Montgomery wondered whether the only truly great men were religious leaders. As Colville recounted: “Churchill’s reply to that interested me, for he seldom spoke of religion. He said that their greatness was undisputed, but that it was of a different kind: Christ’s story was unequalled and his death to save sinners unsurpassed.”

Winston Churchill’s efforts to save the Christian West gave it a mere reprieve—in the decades ahead, it became post-Christian nonetheless. Today, millions are eager to do away with every aspect of our Judeo-Christian heritage in the name of progress, foolishly believing that we can break apart the foundations of our civilization and yet survive. Churchill knew that this was a pernicious falsehood and dedicated his life to defending what he knew was precious. For as he wrote in an essay on Moses, in which he explained why he had been guided by Scripture: “Let men of science and learning expand their knowledge and probe with their researches of the records which have been preserved to us from these dim ages. All they will do is to fortify a grand simplicity and the essential accuracy of the recorded truths which have light so far the pilgrimage of man.”